An alumnus of the Film & Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune, with specialisation in Film Editing in 1991, Sanjib Kumar Datta has made quite a name for himself as a Film Editor par excellence. Besides having lent his talent to more than eighty films in Mumbai and Kolkata, he has also been awarded repeatedly for his work; the Editing trophies on his shelf include the Zee Cine Award for Ek Hasina Thi (2004), the Screen Award for Mardaani (2014), the Filmfare Award (East Zone) for Saheb Bibi Golaam (2016) and the BFJA Awards for Iti Srikanta (2004) and Maya Bazaar (2012). We trace his cinematic journey through a detailed one-on-one chat with him.

Speaking of his earliest brushes with cinema and what led him into the film world, Datta recalls, “The very first film I watched was Haathi Mere Saathi (1971). We used to live in Mumbai then and my father took me to watch the film. I remember I liked the film a lot. The next film I recall watching was Seeta Aur Geeta (1972). This time though, I began howling away inside the theatre but my mother nevertheless wanted to watch the film. As my crying was disturbing the audience, she took me outside and made me sit at a roadside tea stall and went back to watch the film! The tea stall guy was a nice guy who treated me to cups and cups of tea. This was way back in 1973-74.

We then shifted to Kolkata in 1975. I joined a reputed school there called Patha Bhavan. The great Satyajit Ray was a patron of the institution and would often pick up child actors from this school. When he was looking for a boy to play the role of Capt Spark in Joy Baba Felunath (1979), a school teacher took me to his house. At the end of the interview, Mr Ray stood up. Seeing such an imposing figure in front of me, I silently made up my mind to be behind the cameras myself one day. Coincidentally, Nandita Mitra, our neighbour who was once married to the legendary cinematographer Subrata Mitra, came home that evening and told my mother never to allow me to enter the film industry. But by then my mind was made up. I began to read up on films and filmmaking while still in school and acquired a very basic knowledge of what film editing was all about. Post my graduation, I applied for Film Editing at the FTII because I wanted to be in a technical field within cinema.”

Talking of his days in Asia’s premier school, Datta reminisces, “What can I say about the experience at FTII? One has to savor it himself or herself. After a day of classes, each evening we used to have screenings in the Main Theatre. I remember the first film I watched there was The Gay Girls (1960) by Claude Chabrol. I had seen many of the films that were screened at the FTII when I was a student at Jadavpur University. But watching them at FTII was to see them afresh and it was a huge revelation – be it the French New Wave or even the Italian, Polish, Czech and Japanese films. I remember particularly admiring the cinema of Yasujiro Ozu and the profound effect his films like Tokyo Story (1953) and An Autumn Afternoon (1962) had on me. I was also fortunate to hone my editing skills there thanks to the able guidance of my Head of Department, Prof K Ramachandra Rao, and other Editing faculty like Mr Mehboob Khan and Mr Yogesh Mathur.

Unlike Cinematography, which is clearly evident on the screen, good editing is invisible as one juxtaposes shots according to the script in making the film a single entity for the viewer. In fact, a film takes its first shape on the editing table. But even as I contribute to giving a film its shape, pace and rhythm, I have to keep in mind that the director is the captain of the ship. No two ways about it. For me, he or she is the topmost person and the rest of the cast and crew should work hand in hand to realize his vision.”

On life post the FTII, Datta says, “I first went to Mumbai staying as a paying guest in Sundar Villa, a haven for Institute pass outs where we lived like an extended family. I remember Rajesh Parmar, a senior Editing graduate of the Institute. He would come back very late from work every night and we freshers would all shout in chorus, ‘Papa Aa Gaye, Papa Aa Gaye!’ Though he would be very tired, he would say, Chalo Baccho, Khaane Chalte Hain. One more interesting incident I recall is that when I got my first ever payment, I sent Rs 10,000 home. However, the very next week, I had to ask my father for Rs 20,000! He jokingly said, ‘Please do not send us any more money!’”

Datta’s life changed once he joined the late Renu Saluja as her assistant. It was a long and fruitful association and one he continues to cherish. “What do I say about Renu Saluja? The whole of the filmmaking fraternity knows about her and her greatness as a Film Editor. What made her stand out from other Editors was her calm nature and the immense amount of patience she had even as she dealt with directors, old and new. I remember she would hum Hindi songs at times as she worked her way through. But she was also a tough task master and we had to be on our toes throughout to see that the work was done perfectly. It is because of Renu that I got to be involved in the projects of directors like Kundan Shah, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Ketan Mehta and Shekhar Kapur.

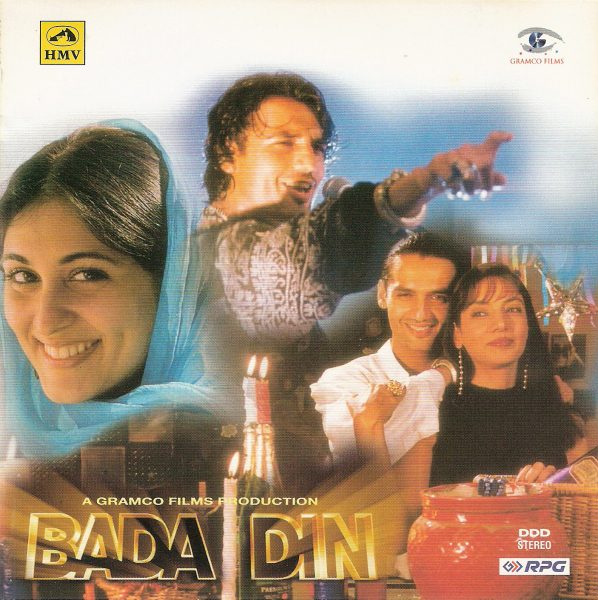

Work aside, Renu was such a lovely person and like a mother to all of us who assisted her. I remember a brief time when I was totally besotted with a bar dancer. Renu, who cared immensely for me, was insistent in going to the Ladies’ bar to meet her. I managed with great difficulty to keep her from doing so. I found it very tough to come to terms with her death. I remember she had a recorded message in her own voice on the answering machine connected to her phone. I would repeatedly call to just listen to her voice. This went on for almost a month after she was no more until the message was finally erased from the machine. It was also thanks to Renu that I got my first independent break as an editor. The film was Bada Din (1998), a Hindi film directed by Anjan Dutt that was shot entirely in Kolkata and focused on the Anglo-Indian community on the brink of celebrating Christmas. Anjanda wanted Renu to do the Editing but she was too busy and suggested my name instead.”

When asked about what criteria he applies to accepting a film, Datta laughs. “Beggars cannot be choosers. If I were to put parameters on deciding which film to take up, I would have to starve!” However, once he is aboard a film, Datta has his own method of work.” I love to do the rough cut on my own. In some cases, if the director has something to say about a particular scene, then I sit with him and go through the rushes of that scene. But on the whole, I normally do the rough cut on my own, giving shape to the filmed material. Of course, I would like to be involved in the film much earlier. But in India, very rarely do the directors sit with their editors on the script and shot breakdown. In most cases, I have entered the film only after the shoot is over. I would love being on the sets while the shooting is going on if possible and have done that but it is extremely rare.”

There have been many changes in technology in filmmaking particularly over the last two decades or so. For someone who first worked with celluloid and edited his films on the Steenbeck, it was no cakewalk for Datta to shift to a Non-Linear platform. Talking about the big switch, he says, “I learnt all my craft on the Steenbeck. So when the Avid arrived, it came like a big jolt. I hardly knew much about computers then and the first couple of weeks were like hell. Pacing, for one, was a major issue. It took quite some time for me to come to terms with Non-Linear Editing.”

On being asked if he had any favourite sequences from his vast expanse of work, Datta mentions, “There is a round trolley sequence in Teen Deewarein (2003), which I feel was edited very nicely. It was tough as I had a full two hours of rushes for that sequence alone. And each take of Naseeruddin Shah was pure gold. Even selecting the right take was not easy. But I’m glad how it all came together at the end. Also, cutting down a three and a half hour long Iqbal (2005) to its final length was very challenging without losing anything from the story. But there have been disappointments too. A film called Kyun! Ho Gaya Na… (2005) was not shot as intended and the blame was squarely placed on my shoulders. Though an editor is bound greatly by the material shot and yet expected to create the magic, it is he or she who is made the first scapegoat if the final film does not come up to expectations. Otherwise as an editor, I feel I can adapt myself to any kind of film provided I am given the appropriate footage.

After years of living in Mumbai, Datta made the shift back to Kolkata in 2011. While he continues to come to Mumbai for work, he has made quite a mark for himself in the world of Bengali cinema as well. Speaking about his move, Datta says, “A lot of people asked me how would I adapt to working in Kolkata? However, I feel filmmaking and editing in particular is the same anywhere in India. One just has to do it with the same level of integrity and passion.”

Finally, when asked where he would like to go from here, Datta rounds off by saying, “I have always been comfortable as a Film Editor and hope to be just that for the rest of my life.”

Really good article about sir.

Hope I would like like to get read such articles On editor and other technicians too.

Powerhouse of creativity & talent…Each finding a great communion in his works.. may he carry on the good work & continue to enthrall his audiences 🙂

Dear Sanjib Dutta. I want to meet you. The first film u did as an assistant editor for 1942 A love story. When u stay in PMGP COLONY ANDHERI Mumbai. Ground floor.

YOUR FAN

An awesome talent and a gentle soul with an eye for perfection .He will win more laurels and will be part of great films.Well.spoken in the interview.very articulate.Amongst the best of his batch.very gifted.loves songs of Kishore Da and supports East Bengal.

??

Like your comments my dear friend – I want you to reach the top of the editing world

Shocking ???