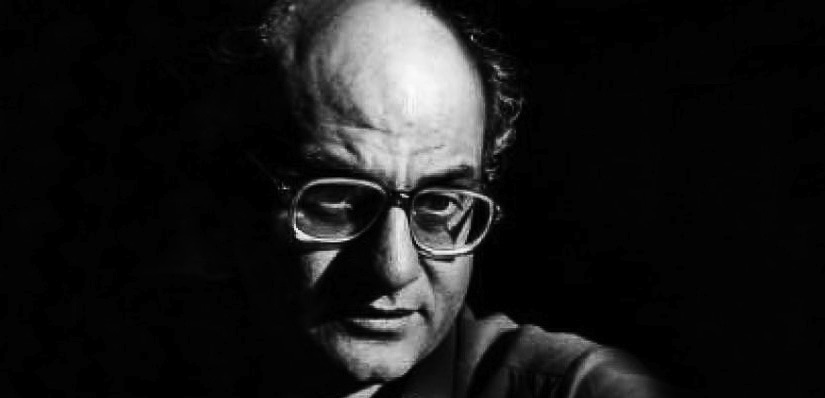

Mani Kaul is a pioneer of the Indian New Wave and undoubtedly the Indian filmmaker, who, along with Kumar Shahani, has succeeded in radically overhauling the relationship of image to form, of speech to narrative, with the objective of creating a ‘purely cinematic object’ that is above all visual and formal.

He was born Rabindranath Kaul in Jodhpur in Rajasthan into a family hailing originally from Kashmir. His uncle was the well-known actor-director, Mahesh Kaul, who had helmed films like Gopinath (1948), Naujavan (1951), Sautela Bhai (1962) and Sapnon Ka Saudagar (1968). Mani joined the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune initially as an acting student but then switched over to the direction course at the institute. He graduated from the FTII specialising in Film Direction in 1966.

Mani’s first film, Uski Roti (1970), was one of the key films of the ‘New Indian Cinema’ or the Indian New Wave. The film created shock waves when it was released as viewers did not know what quite to make of it due to its complete departure from all Indian Cinema earlier in terms of technique, form and narrative. The film is ‘adapted’ from a short story by renowned Hindi author Mohan Rakesh and is widely regarded as the first major formal experiment in Indian Cinema. While the original story used conventional stereotypes for its characters and situations, the film creates an internal yet distanced kind of feel remniscent of the the great French Filmmaker, Robert Bresson. The film was financed by the Film Finance Corporation (FFC) responsible for initiating the New Indian Cinema movement with Bhuvan Shome (1969) and Uski Roti. Uski Roti on one hand was violently attacked in the popular press for dispensing with standard cinematic norms while on the other, it was vehemently defended by India’s aesthetically sensitive intelligentsia.

Kaul followed Uski Roti with Asadh Ka Ek Din (1971). This film is based on a play by Mohan Rakesh and is set in a small hut in the hillside and features on three characters: Kalidasa (Arun Khopkar), Mallika (Rekha Sabnis) and their friend, Vilom (Om Shivpuri). The characters’ lines, mostly monologues, were pre-recorded and played back during shooting, thus freeing the actors from theatrical conventions. A highlight of the film is KK Mahajan’s sensuously shot landscapes and languid, loving camera movements.

Duvidha (1973), Kaul’s third film, was also his first in colour. Derived from Vijaydan Detha’s short story, the film tells of a merchant’s son (Ravi Menon) who returns home with his new bride (Raisa Padamsee) only to be sent away again of family business. A ghost witnesses the bride’s arrival and falls in love with her. He takes on the husband’s form and lives with her. She has his child and then to complicate matters, the real husband reaches home. A shepherd finally traps the ghost in a bag. The film uses the classical styles of Kangra and Basohli miniature paintings for its colour schemes and framing and focuses on the wife’s life, developing the characters through parallel, historically uneven and even contradictory narratives. The film is a very finished and polished product and one of Kaul’s best known films, shown widely across Europe. The film also won the National Award for Best Direction. A few years back, Amol Palekar did a less than satisfactory adaptation of the same story as Paheli (2005), starring Shah Rukh Khan and Rani Mukerji.

Mani Kaul, along with K Hariharan and Saeed Akhtar Mirza, as well as other filmmakers set up the Yukt Film Co-operative (Union of Kinematograph Technicians) in 1976. This led to a remarkable avant-guard experiment in collective filmmaking as the group made Ghasiram Kotwal (1976), one of the most celebrated plays in Indian Theatre. The play was staged by the Theatre Academy Pune in 1972 and its members participated in the film’s cast as well. The film, though commenting on Maratha and Indian history, has more contemporary ramifications as it explores metamorphically Indira Gandhi’s reign and the period of ‘Emergency.’

In Mani Kaul’s cinematic conception, fiction and documentary films have no clear demarcated dividing line. Quoting filmmaker Putul Mahmood, who also worked with Kaul, “Mani Kaul’s documentary films, often neglected, are easily India’s most acutely original, avant garde and experimental films. I’d say Mani Kaul is India’s most significant documentary filmmaker.” In an interview, Kaul himself said, “All my life I have tried to find different ways to do away with a linear narrative. This is why I was interested in documentaries. I find the documentary form very interesting, and within it the poetic documentary.” Indeed, films like Dhrupad (1982), Mati Manas (1984) and Siddheshwari (1989) have a rare cultural intensity where poetry, fiction and the documentary have been successfully fused together. Dhrupad explores the origins of dhrupad through its evolution to the classical form to which it is known today. Mati Manas rises above the documentary form and traces the development of pottery down the ages in the sub-continent while Siddheshwari is based on the life of the great eponymous thumri singer of Varanasi. The film won the National Award for the Best Arts/Culture Film, the jury’s citation stating, “For its innovative and stylised interpretation of a singer’s work and her milieu.”

With Nazar (1989) and Idiot (1991), Kaul turned his attention to the writings of Dostoevsky. The former is based on Dostoevsky’s story The Meek Creature and a major part of the film, which also has references to Bresson’s Une Femme Deouce (1969) based on the same story, chronicles the young wife’s alienation in a disintegraing marriage as she first resists and then succumbes to the order of things in a world in which her place is determined regardless of her efforts to intervene. The film’s strength lies in the visual force which beautifully conveys the ambience of claustrophobia and auto-destruction.

Idiot was made as a four part TV series for Doordarshan running 223 minutes and edited down to 180 minutes feature length. Kaul commented on Idiot that “Whereas for years I dwelt on rarefied wholes where the line of the narrative often vanished into thin air, with Idiot I have plunged into an extreme saturation of events. Personally I find myself on the brink, exposed to a series of possible disintegrations. Ideas then cancel each other out and the form germinates. Content belongs to the future and that’s how it creeps into the present.”

Mani Kaul’s last feature to date has been Naukar Ki Kameez, made in 1997 but released in 1999. The film, based on Vinod Kumar Shukla’s novel of the same name, looks social hierarchy within an Indian village in the 1960s and, in particular, how the structure affects a fairly low-paid clerk and his wife. To most viewers, it is easily his most accessible piece of work while to hardcore Mani fans, it is his most disappointing film for precisely the same reason!

After a stint in Netherlands teaching music, Mani Kaul worked as the Creative Director of the Film House at Osian’s Connoisseurs of Art, Mumbai.

Mani Kaul passed away in Gurgaon on the outskirts of New Delhi on July 6, 2011. He had been ailing for sometime.