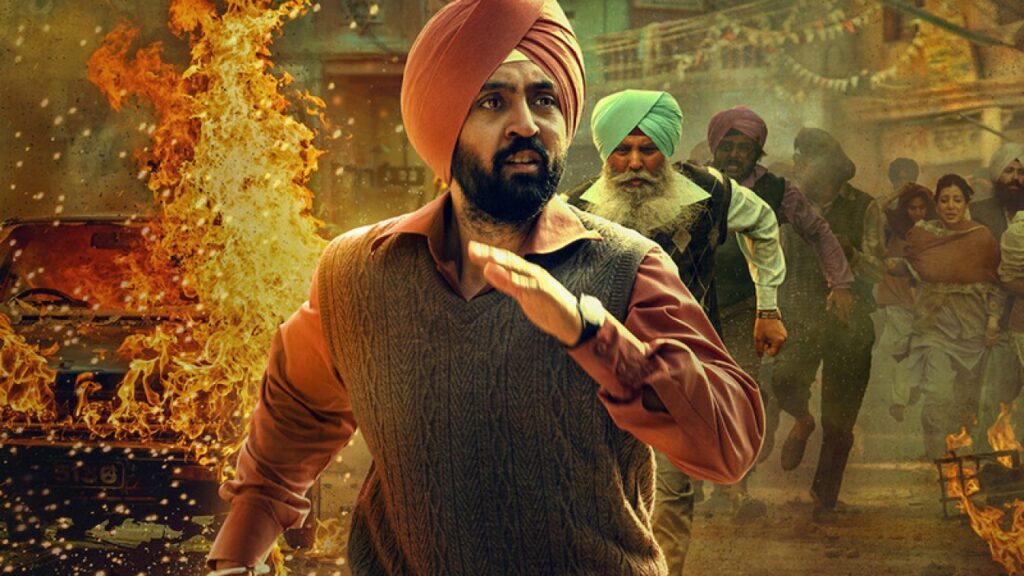

Ali Abbas Zafar’s Jogi (2022), currently streaming on Netflix, is set in 1984 against the backdrop of the horrific Sikh genocide that took place in New Delhi following the assassination of then Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, by her two Sikh bodyguards. Even though the filmmaker, admittedly, steps out of his comfort zone from his previously lavishly mounted efforts like Gunday (2014), Sultan (2016) and Tiger Zinda Hai (2017), to attempt a more humane story, he fails to go any deeper or give us a fresh, layered or nuanced take on this extremely dark chapter in India’s history.

Jogi is set over a span of three days, beginning with the morning of 31st October, 1984, when Indira Gandhi is assassinated. Joginder Singh aka Jogi (Diljit Dosanjh) lives happily with his family in the fictitious locality of Trilokpuri, a Sikh neighborhood in Delhi. Jogi’s father is about to retire and is to attend a farewell function at his office. As the father and son board a city bus, the other passengers turn on them and throw them out of the vehicle. As the duo realize what has happened and make a dash back to their neighborhood, the carnage against Sikhs has already begun. The councillor of the area, Tejpal Arora (Kumud Mishra), assigns the task of killing the Sikhs to dreaded convicts while ordering the police to turn a blind eye to the ensuing rampage. Inspector Rawinder Chautala (Zeeshan Ayyub), a friend of Jogi, informs him about the inhuman intentions of the administration. He offers to ride Jogi and his family to safety in Punjab. However, Jogi refuses. He would not leave like this, not without his neighbors, who are hiding in the Gurudwara. Jogi and Rawinder then go to another of their friends, Kaleem Ansari (Paresh Pahuja), to help them with a truck for carrying out the rescue mission. Whether Jogi succeeds or not is what the rest of the film is about.

Jogi engrosses us initially as Zafar and his co-screenwriter, Sukhmani Sadana, immediately cut into the crux of the tension within the first few minutes of the film. To his credit, Zafar aims to give some subtlety and restraint to the story in order to keep it on a more humane level. The film also tries to explore, though superficially, the dangers of being a minority community in India and their plight if the majority decide to turn against them. And that too with collusion from the powers that be. Zafar also reiterates there are good people everywhere. By representing Jogi’s close friends as a Hindu (Rawninder) and a Muslim (Kaleem), he displays that in moments of crisis, humanity has the power to dissolve the barriers of religious divides. Interestingly, like with V Shantaram’s classic film on communal harmony, Padosi (1941), a Hindu actor plays the Muslim character and vice-versa. In one key scene, as Jogi is about to embark on his journey with a false get-up, Kaleem ensures the ‘kada’ is removed by all those moving towards safety so they are not recognized by their religious symbols. But perhaps the film’s most poignant sequence occurs when Kaleem opens the door of his house and finds Jogi standing there with his turban removed and hair chopped off and he is unable to identify his childhood friend.

Despite such moments and in spite of some finesse in the storytelling, there is much in the writing that lets the film down. Most importantly, the film is unable to go into the depth and layering its heavy subject matter demands. This is perhaps due to giving more focus to the thriller aspect of the story as against drama and focussing on more human moments. Other irritants include the love story between Jogi and Kammo (Amyra Dastur), which eventually becomes a bone of contention between Jogi and his friend, Lali (Hiten Tejwani). It is sluggishly integrated within the framework of the narrative. Lali, who has been seething for having lost Kammo and will not let go of any opportunity to have his revenge against Jogi, changes his mind after a brief verbal encounter with the latter. This makes for such a convenient and unconvincing twist.

Diljit Dosanjh brings much sensitivity to his character as a young man ready to risk his own life for the sake of his community. We empathize with him and cannot help but be moved when he removes his turban and cuts his hair off. Zeeshan Ayyub brings much intensity as a man ready to help his friend unconditionally. However, Paresh Pahuja and Hiten Tejwani do not make much of an impact due to their sketchily conceived characters. Amyra Dastur in her cameo as Jogi’s love interest brings some spiritedness and joie de vivre to her role. And expectedly, Kumud Mishra scores as the two-faced politician out to make the most of the riots.

Marcin Laskawiec’s camerawork and lighting effectively brings out the horror of the violent and the anguish of those just wanting to survive. Steven H Bernard maintains the fast pace of the film to avoid any lags or dull moments. The background score by Julius Pachiam sets the right note in stimulating the emotional core of the film. However, the production design is a let down. It gives us the feeling that the entire neighbourhood of Trilokpuri was erected on a set and takes away much of the authenticity of the milieu of the film.

Jogi is finally a lost opportunity for Zafar as he prefers to shy away from making any socio-political commentary and plays safe by reducing it mostly to a display of his aptitude in storytelling. This robs the film of its potential of what could have become one of the best and most significant films of the year.

Hindi, Punjabi, Thriller, Drama, Color