“Give me two photographs, a music and a moviola. And I’ll give you a movie.” is a quote that is famously indentified with Cuban documentary filmmaker Santiago Alvarez.

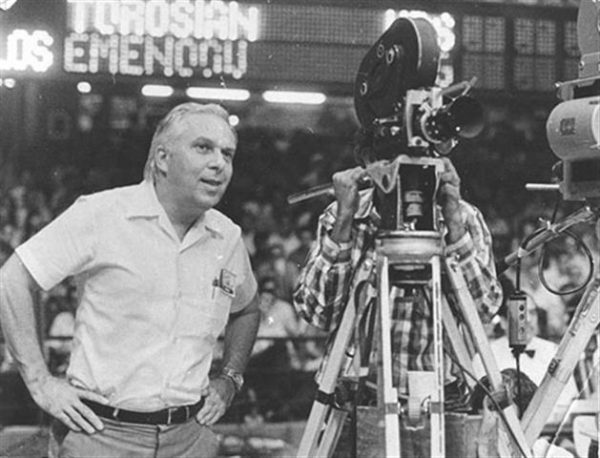

Alvarez, born on March 18, 1919, predominantly dwelled within the newsreel format of filmmaking, heading the Cuban Film Institute’s (ICAIC) newsreel division, Noticiero ICAIC, in 1960s post-revolution Cuba. Working with leftover antique equipment of the pre-revolution era and having to address the political need to quickly and consistently share the post-revolution euphoria within Cuba and outside with the world, Alvarez developed a distinct style of the newsreel format that was personal, easy to relate to and that which went way beyond the mundane form of reportage that is normally associate with the format.

Alvarez was a product of his times. The Cuban revolution under Fidel Castro, whose armed struggle overruled the then corrupt Cuban political regime, set in motion of a series of reforms that saw the Nationalization of assets, giving rights to blacks and women and enhancing health care, housing, education and communication. Supporting this ‘reconstruction of a nation’, so to say, was to be the focus on art forms. It was not just the content that was rebellious. Formal experimentation was encouraged for the purpose of creating a ‘new public’. In the words of Fidel Castro it was “All within the Revolution; Nothing outside it.” It was in this context that the ICAIC was started and Santiago Alvarez made to head its newsreel section.

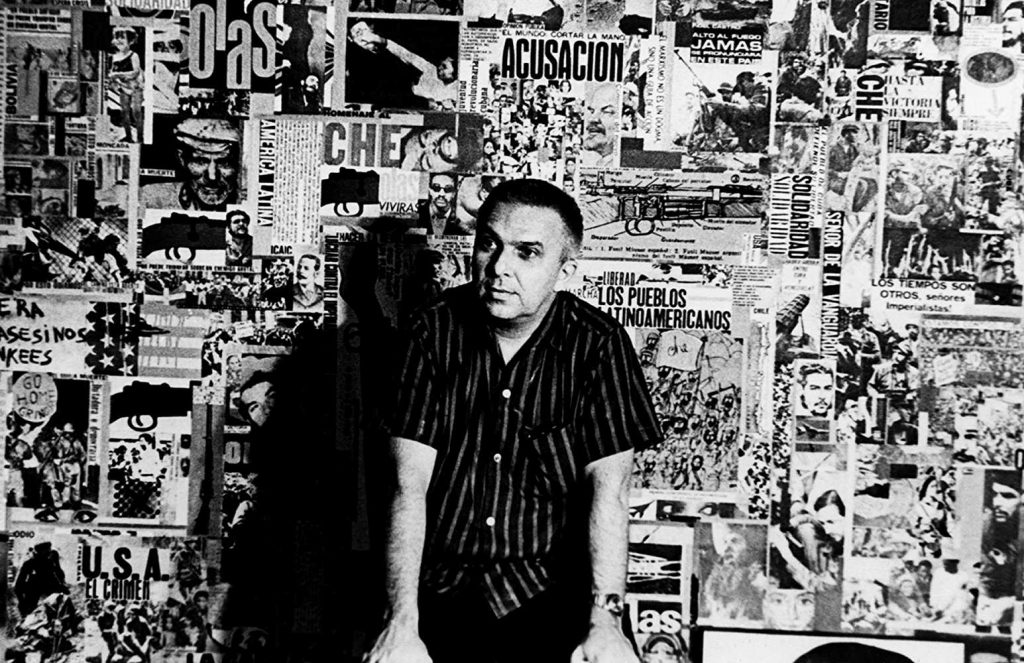

Alvarez’s trademark aesthetics include the use of ‘found’ material – be it live footage or photographs, the employment of text as graphical images and more significantly, the dynamism of editing which he called the nervous montage – evoking feelings, emotions and interpretative connotations by juxtaposing two shots, using visuals and sound, music and sound effects, and at a macro level, structurally juxtaposing seemingly different layers of thoughts knit around loose narrative strands. He also did away with the use of commentary that guided the audience to extensively use music, poetry and songs instead. However formal his techniques may seem, his films are open to multiple elucidations making them poetic in the process.

Detached objective reality was alien to Alvarez and therefore his work is seen as an antithesis to the Griersonian school, the direct cinema observatory approach and the anthropological documentary. His films, however, bond him directly to Dziga Vertov, who was operating in similar cultural and political conditions decades before him in the erstwhile USSR.

The thematic concerns of Alvarez’s films naturally stems from the concerns of the revolution. American Imperialism, Neo-Capitalism, Racism, De-colonization, Nation building, and solidarity with other international people’s movements are some of the issues explored by Alvarez, in his own indefatigable style. His films not only mirror the realism of Cuba of its time, but also that of the entire Latin American region, parts of South East Asia, Africa and the East European block.

Now (1965), is a five-minute film on racial discrimination in the USA with a call for an action against it. It uses a few photographs and the radical title song, then banned un the USA, sung by the African-American singer, Lena Horne. LBJ, made in 1968, is a 18-minute film that implicates the then American President, Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ), to the deaths of Martin Luther King (L), Bob Kennedy (B), and John F Kennedy (J). And How, Why And For What General is Killed (1971), in a thrilling approach, looks at the assignation of General Schneider in Chili by local right-wing groups backed by the CIA.

Hurricane (1963) is a lyrical film that deals with the devastation that Cuba underwent after it was hit by a natural calamity and the subsequent healing process that took place. The film is constructed only through music and sound effects. The Forgotten War (1967) deals with the underground resistance movement in another South East Asian country, Laos, again without an obvious voiceover, showing only the resistance activities held inside deep caves. Hanoi, Tuesday 13th (1968) looks at the USA’s military aggression in Vietnam, while the filmmaker himself was present in the city of Hanoi when the bombings had started. The impressionistic 79 Springs is an account of the life of Vietnamese poet, guerrilla fighter and statesman, Ho Chi Minh, on the occasion of his death. Made in 1969, it connects his work on the resistance to the Vietnam war to people’s movements elsewhere in the world. My Brother Fidel (1977) deals with Fidel Castro’s encounter with a blind 93-year associate of Cuban nationalist literary figure, Jose Marti. Ever Onward to Victory (1967) is a tribute to the revolutionary leader Che Guevara, made in just 48 hours after his death.

As the euphoria over the revolution plateaued in Cuba, it would seem that Alvarez’s methodology too got sober. The length of his films increased, their pace decreased, and he began using conventional voiceover commentary guiding the overall narration. There was less of his dynamic ‘nervous montage’ that made him the filmmaker that he was. Instead, he took to the observational mode.

Prominent among Alvarez’s longer films are The Necessary War (1980) that uses the testimonials of the key players of the Cuban Revolution and the one that he made on Vietnam, April of Vietnam in the Year of the Cat. It uses footage that he and his team had extensively shot over their numerous visits to the country and it comprehensively deals with the US invasion of Vietnam; and the resistance it faced. The last-named film, made in 1977, is also about Fidel Castro’s visit to Vietnam. This film had followed a series of other similar ones dealing with Castro’s foreign visits aligned with the then Cuban foreign policy of supporting certain sympathetic international causes. These films include Born of the Americas (1972) and And Heaven Was Taken by Storm (1973) looking at when Castro visited Chile, East Europe and Africa respectively. Such films were structured around Fidel Castro’s long speeches in the various places he travelled to. Critics could not but get a feel that the films were mere mouthpieces of Castro’s policies.

Santiago Alvarez saw himself as a political agitator, who, like a journalist, did not want to take too long to put across his ideas to his audience. The reality, he said, needs to be told cinematically or aesthetically; and with the urgency that the people require. Posterity did not fall in his scheme of things. He made over 700 films in his career, beginning in 1959 right upto his death in 1998. These included short and long films and even the occasional fiction films.

“Necessity is the mother of invention.” wrote the Greek philosopher Plato. Santiago Alvarez’s body of work is as fine an exemplification of this as any.

Nice