Director Jacques Tourneur (1904-1977) will always be remembered for helming one of the greatest film noirs of all time, Out Of The Past (1947). This film, to me, is perhaps the second greatest film noir of all time from the classic era of noir – the 1940s and ’50s – and just a shade behind Billy Wilder’s undisputed masterpiece, Double Indemnity (1944). Out Of The Past also sees perhaps the deadliest femme fatale of them all, Jane Greer, ahead of even spider woman Barbara Stanwyck in the Wilder classic.

But before he directed Out Of The Past, Tourneur had made quite a name for himself for his three B-films for producer Val Lewton (1904-1951), who at the time was heading the horror unit at the RKO studio. With these three films, Tourneur, said to be a major believer in the occult and the supernatural, proved just how exciting the world of the B-film could be if tackled right and having the correct producer backing the director. In the days of the Hollywood studio system, these low-budget films were mostly the less publicized halves of a ‘double bill’ or double feature programme with a running time of up to little more than an hour. While no doubt, many B-films were inexpensive exploitative films, Tourneur, thanks to the support of Lewton, illustrated just how they could also be highly imaginative and a basis for far more personal expressions of filmmakers. For one, there was less interference from the Studio bosses on these films as compared to prestigious ‘A’ pictures. This left the filmmaker with more creative opportunities to move away from the formulaic and infuse a high degree of cinematic craft and artistic ingenuity into his/her work as each of these three Tourneur films prove.

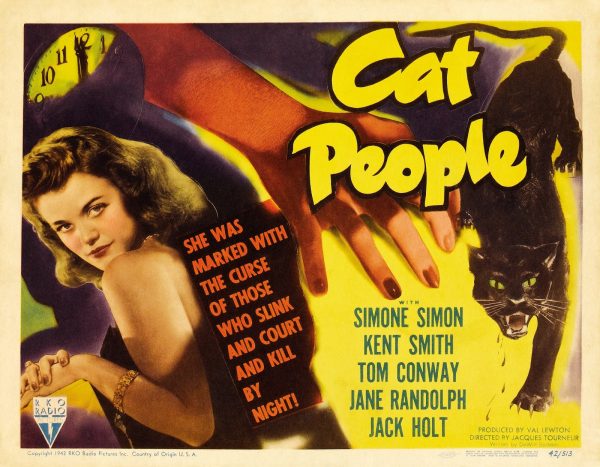

Cat People (1942)

Just how highly Cat People is regarded can be gauged from that the fact that Martin Scorsese features it predominantly in his segment on the world of B-films, The Director As Smuggler. The segment is a part of his brilliant documentary series – A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies (1995). In fact, according to Scorsese, the film’s aesthetics, craft and influences on future filmmakers make it as important a film as Citizen Kane (1941), no less, in its own way in American cinema history. Cat People is easily the best of the Tourneur-Lewton collaborations and a film that amply illustrates that money has little to do with cinematic artistry. In fact, the meagre budget dictates the style and treatment of the film where very little of the obvious is seen. A fine building up of a frightening atmosphere leaves much to the audience’s imagination, thereby making for rich viewing.

In the film, Simone Simon plays a young Serbian woman in America who fears intimacy as she believes she has descended from the devilish ‘cat people’ of centuries ago from her village. She falls in love and marries a young man (Kent Smith) but resists from consummating the marriage, fearing if she did so, she would turn into a deadly, murderous black panther. With no money to play around, Tourneur plays instead on creating the film’s chilling and mysterious atmosphere without ever showing the killing creature on-screen but depending instead on highly expressionist low-key lighting with stunning use of the darkness and skilfully using simple but effective devices like the eerie rustling of trees at night or ominous shadow play to suggest the threatening presence of the ‘cat-woman’.

Cat People is also lovingly referenced in Vincente Minnelli’s biting film on Hollywood, The Bad And the Beautiful (1952), wherein director Barry Sullivan and producer Kirk Douglas (based somewhat on Lewton) are assigned to make a cheap horror film, Doom Of The Cat Men, and they get their way around it artistically by hinting that the ‘dark has a life of its own’ and thereby making a film where they create the most terrifying atmosphere without ever showing the Cat Men!

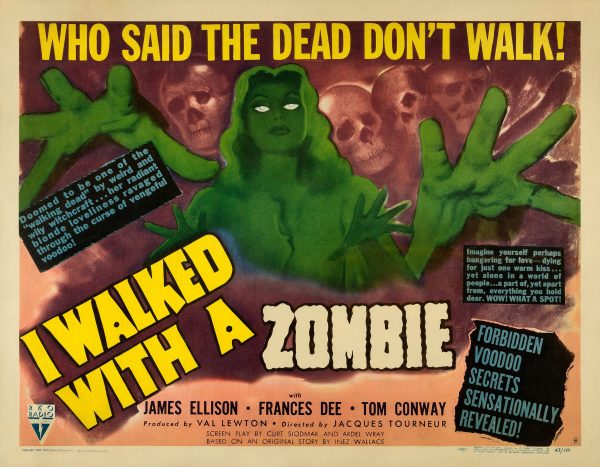

I Walked With A Zombie (1943)

This one, also referenced by Scorsese, deals with voodoo, witchcraft, black magic and the occult as a Canadian nurse (Frances Dee) takes up a job as a nurse to care for a catatonic woman (Christine Gordon), also the wife of a sugarcane planter (Tom Conway) in the island of St Sebastian in the West Indies. When the ‘zombie’ woman fails to respond to modern medicine and the nurse’s tender care, the latter, having fallen in love with the planter, resorts to get his wife back to him no matter what by taking the woman to the local witch-doctor to try and cure her…

The plot mixes the horror-sorcery genre quite successfully with elements borrowed from Charlotte Brontë’s novel, Jane Eyre (1847). To Tourneur, it was a West Indian adaptation of the Brontë classic even as he pits the voodoo rites of the natives against, of course, the scientific and benevolent ‘saner’ methods of the white people. Sure enough, taking the woman to the locals for ‘treatment’ leads to a chain of events that ends up in tragedy. The political incorrectness aside, though Tourneur does mention the evil effects of colonialism and slavery, the filmmaker majorly succeeds again, as in Cat People, more in creating an eerie and tension-filled mood through the noirish lighting and his smart selective choice of what to show and what not to. A particularly well-executed sequence is when the nurse takes her patient through the sugarcane fields at night towards the location where the natives indulge in their rituals.

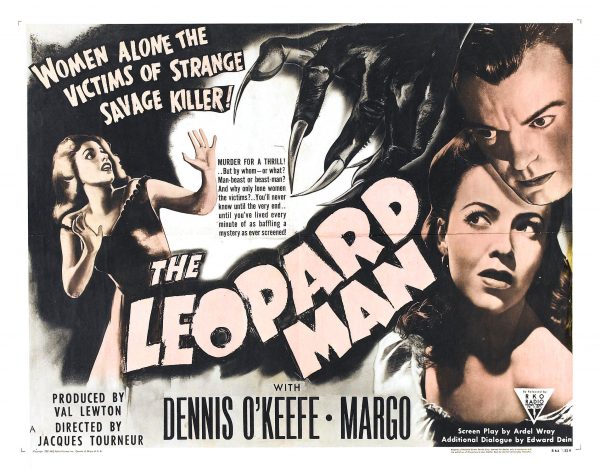

The Leopard Man (1943).

While no doubt having its strong moments, The Leopard Man is perhaps relatively – and I stress on relatively – the weakest of the three Tourneur B-films though effective enough. In the film, a publicly stunt involving a nightclub singer (Jean Brooks) walking into the club where she performs with a leopard as a pet on a leash goes horribly wrong when the beast escapes. Soon, more deaths occur of three women ostensibly done by the leopard. But doubts persist. Is it really the leopard? Or is it a man behind the gruesome killings?

The Leopard Man sees some wonderful cinematic flourishes like the first killing ‘seen’ from the other side of a wooden door (see accompanying clip), and the killings, true to the Cat People formula of not showing the creature, are never shown directly on camera but off-screen thereby being all the more effective. The film is further aided by some great expressionist cinematography and fine, suspenseful build ups leading up to each of the murders. However, the script has less meat as compared with Cat People and I Walked With a Zombie. The end, too, is none too satisfying with the identity of the killer seen a mile away and his motivations for the killings aren’t dealt with much depth either.

Sadly, Tourneur never got his due post the 1950s. It was said that he was so determined to direct Stars in my Crown (1950) – starring Burt Lancaster and Virginia Mayo and another fine film in his oeuvre – that he took a ridiculously low salary just to direct it. This is thought to be the death knell in his career as he was thereafter mostly relegated to marginal B-films and TV episodes befitting his new salary. It’s a pity that this time, he couldn’t rise above his material as spectacularly as he did in his glory days. Fortunately, these 3 films and Out of the Past show us just what Tourneur was capable of at his best. And why exactly the next generation of filmmakers like Scorsese rates him ever so highly.