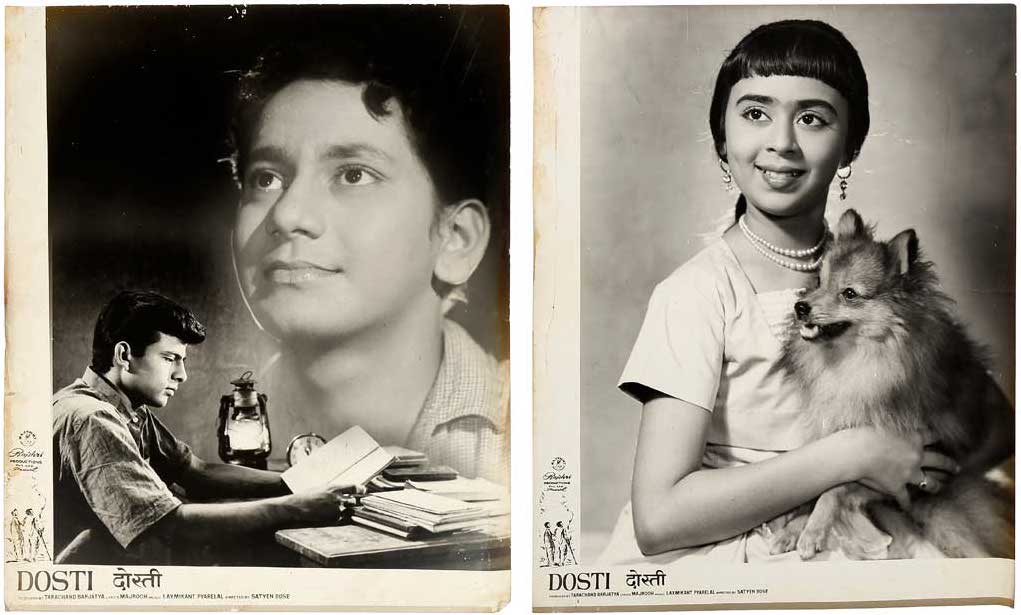

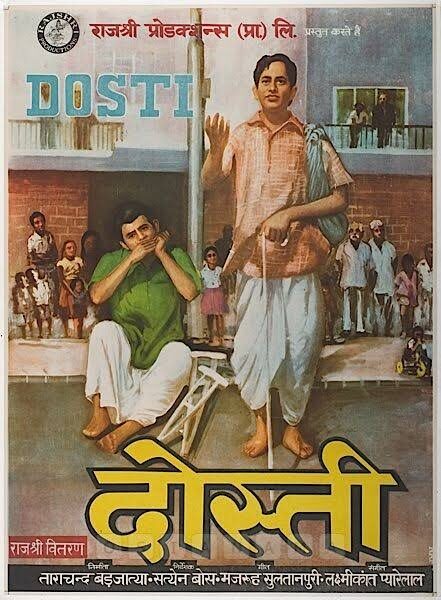

It was a mildly winter day in Bombay, on November 6, 1964. A bunch of us kids weren’t quite thrilled about zipping to the Naaz cinema for the first day, first show of the starless, no buzz-about-it, black-and-white, barely advertised film, Dosti, directed by Satyen Bose (1916-1993). This was the second offering of Rajshri Productions’ Tarachand Barjatya after Aarti (1962).

That Ashok Kumar-Meena Kumari-Pradeep Kumar triangular melodrama, directed by Phani Majumdar, concerning the conundrum of medical ethics, had been much too heavy duty for us pre-adolescents. The film had picked up a Filmfare Best Supporting Actress Award for Shashikala whom we dreaded for her wicked, wicked ways on screen. Moreover, the radio would keep blasting its songs Kabhi Toh Milegi and Ab Kya Misaal Doon Main Tumhare Shabaab Ki composed by Roshan, at a time when we were crazily into rock and roll. All indications pointed towards Dosti being more burdensome than baggage carried by a coolie.

Since a friend’s father, a film financier, had handed over free tickets, intending to get feedback from us after the show, the four of us dost log, weren’t the sort to refuse. To our lifelong astonishment, at the end of the 2 hour 43-minuter we came out of Naaz, chastened after crying a river of tears. Our feedback to the financier was that after a week or two, we would like to see the film again, to which our benefactor beamed like a lighthouse.

Something had changed perceptibly in us, this story of two physically-challenged buddies – one blind and possessed of a golden voice, the other lame a proficient harmonica player — was as much of a heart-marauder as the Raj Kapoor produced Boot Polish (1954) directed by Prakash Arora, Bimal Roy’s Devdas (1955), and V Shantaram’s Rajkamal Studio’s Toofan aur Diya (1956) directed by Prabhat Raj. Help, we must have said to ourselves, “We are suckers for tear-jerkers”, never mind if we would invariably return home separately under a cloud of depression, and preferred upbeat, sunshiny endings. Now, the divide between ‘sad’ and ‘happy’ movies was fading for us, forever.

Incidentally, we were hopelessly addicted to songs on Radio Ceylon’s Binaca Geetmala, curated with tremendous elan by Ameen Sayani. Instantaneously, after the release of Dosti, the upcoming composers Laxmikant-Pyarelal had clearly created a series Binaca Geetmala toppers, an unforgettable soundtrack with the five Mohammed Rafi songs, Chahoonga Main Tujhe Shyam Savere, Mera Toh Jo Bhi Kadam Hai, Koi Jab Raah Na Paaye, Raahi Manwa Dukh Ki Chinta, Jaanewalo Zara Mudke Dekho Mujhe, and the Lata Mangeshkar rendered lullaby Gudiya Humse Roothi Rahogi.

Of the acting crew, Sanjay Khan, a newbie at the time, was the only familiar face in a brief role. Baby Farida,portraying his kid sister, was shown suffering from a rheumatic heart disease. A kind soul, she befriends the beleaguered friends and hopes to rehabilitate them. A much sought-after child actor then, she now goes by the name of Farida Dadi and is seen as aunts and grandmamas in films and TV series.

Grossing over Rs 2 crore, in those days, Dosti won six Filmfare awards from the seven nominations that it received. Best Film: Tarachand Barjatya, Best Music: Laxmikant Pyarelal, Best Story: Ban Bhatt, Best Dialogue: Govind Moonis, Best Male Playback Singer: Mohammed Rafi for Chahoonga Main Tujhe Saanjh Savere, and Best Lyricist: Majrooh Sultanpuri for the same song. Tarachand Barjatya’s gambit of an unshowy, devoid of glamour, small-budget film, had paid off and how! It was screened at the fourth Moscow International Film Festival. At home, a Telugu remake, Sneham (1977), followed. And as late as in 1999, there was a ‘inspired’ Malayalam remake titled Vasanthiyum Lakshmiyum Pinne Njaanum.

Piquantly, there was a Pakistani clone of Dosti. According to a link from Pakistan Film Magazine (pakmag.net), “A memorable patriotic and musical film with President of Pakistan, Field Marshal General Muhammad Ayub Khan (in attendance) was screened after his famous speech on the morning of September 6, 1965 when the Indo-Pak war erupted… in the background was the patriotic song Yaad Karta Hai Zamana Unhi Insanon Ko… Ironically, the film Hamrahi was a copy of India’s Dosti, and the story was about two disabled persons and their friendship.” By the way, Pakistan’s Hamrahi (1966) is on YouTube and the full film can be viewed here.

So that was the Satyen Bose-directed Dosti, which still hasn’t assumed, the status of a cult film. Yet for sure, on watching it today, it reconfirms that cinema possesses the manipulative, no-tear-ducts-barred power to make us conjoin with luckless characters, and become one with their harrowing trials and tribulations.

In addition, after the re-look I couldn’t help wondering about the lead actors Sudhir Kumar and Sushil Kumar – whatever happened to them? Where are they today? Real life wasn’t as cruel to them, was it? The answer’s yes and no. Sudhir Kumar is no more; Sushil leads a low-profile, hopefully content life.

Sudhir was around two and half years younger and lived in the industrial neighbourhood of Lalbaug. Sudhir and Sushil were family friends who often visited each other’s homes. Of the two, Sushil had already featured in Arjun Hingorani’s Abana (1958) as a child actor. The film was headlined by Sheila Ramani, besides marking the debut of Sadhana Shivdasani. A Sindhi language film, set between pre- and post Partition, Abana was the first look at the Sindhi Hindu community having to leave Sindh and migrate to India.

Alarmingly, Sudhir Kumar (birth name Sudhir Sawant) — who portrayed the blind singer Mohan — the social media grapevine, had claimed was involved in a fatal freak accident while having a meal. Others insisted that after acquiring fame with Dosti, he had become enmeshed in the underworld and had been murdered in gang warfare.

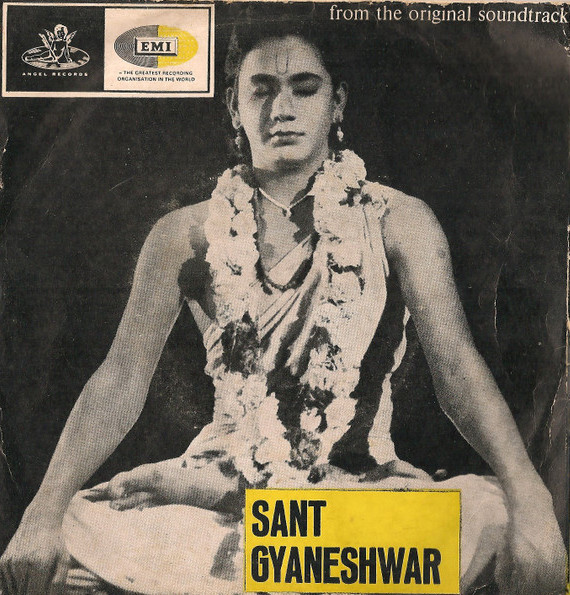

In response, the youngest of his two sisters, Mrs Suchitra Khopkar, has categorically stated, “I would like to clarify that neither did Sudhir die of a chicken bone stuck in his throat nor was he ‘murdered’. The fact is that he passed away because of cancer on January 12, 1993.” With a sense of pride, the sister added that Sudhir who portrayed the blind friend, Mohan, wasn’t jobless after the whopping success of Dosti. His filmography comprises Sudarshan (1967), Annapurna (1968), and Gharchi Rani (1968), all in Marathi, and Sant Gyaneshwar (1964), Laadla (1966) and Jeene Ki Raah (1969) in Hindi. “Unfortunately, after that he didn’t receive much support” she added stoically, “from either Marathi or Hindi filmmakers.”

Harsh and debatable reports have claimed that Sudhir Kumar “could have shown maturity when he achieved public recognition by sticking with the Rajshris and waited for the second film which the production banner wanted to launch with Sushil and him. But Sudhir acted up and signed AVM’s Laadla, not without paying a hefty compensation for breaking his contract. As a result his name was tarnished forever in the film business in which Tarachand Barjatya, as a distributor and producer, commanded high respect.”

By contrast, Sushil Kumar (surname Somaya), who enacted the lame Ramu, perhaps understood that patience pays. He was featured in the cast of Rajshri’s Taqdeer (1967), directed by A. Salaam from his own Konkani film Nirmon (1966), another weepie with Bharat Bhushan, Farida Jalal and Johnny Walker. Although lauded for its music by Laxmikant-Pyarelal (Jab Jab Bahar Aaye Tum Mujhe Bhaut Yaad Aaaye and Saat Samundar Paar Se were a rage) the family melodrama did not create the desired waves at the ticket windows. Subsequently, Sushil in the quest of security, joined Air-India as a cabin manager, and was last heard of as a retired family man residing at the Navjivan Society, Chembur.

A sleeper hit like Dosti happens rarely. The two lead actors had knocked out incredibly believable performances. Their chemistry was so palpable, that of late analytical studies, have theorised that unwittingly their characters had obvious gay connotations. Gay activist Ashok Row agrees, going to the extent of stating, “I would even say Dosti was India’s first gay film. It showed homo-erotic elements between the two friends without demeaning either of them.”

Be that as it may, the more valid point is why cinema coerces viewers to a catharsis, of releasing our pent-up feelings, shedding tears even though we are aware that we are watching a make-believe story. One psychological reading of this is paradoxical: it could be either a sign of emotional weakness or an indicator of emotional strength.

Uncannily with Dosti, Satyen Bose, who had the knack for helming weepies — what with Jagriti (1954), the Daisy-Honey Irani sniffler Masoom (1960), Mere Lal (1966) and Aasra (1966), as well as the iconic comedy Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi (1958) — had routed us into the world of his characters Mohan and Ramu. We felt as Mohan and Ramu felt, identifying with their struggle to live in a world without pity. We knew they are not real, but we were so engrossed that we emotionally reacted as though they were.

The widely-respected American neuroscientist Paul Zak on studying the effects of compellingly touching stories, has theorised that these can cause the release of oxytocin – best known for its role in childbirth and breast feeding, increasing contractions during labour and stimulating the milk ducts. As social animals, our survival depends on social bonding. And oxytocin is critical, helping us to identify and attach with our essential caregivers and protective social groups.

Conventionally, it is believed that big boys don’t cry. Indeed,most boys learn from an early age that crying in public will make them look weak. However, this is nothing but a nonsensical limitation. Boys and girls, when they’re young, don’t differ at how much they cry. It’s a human response that is not related to any particular gender, and that is known to those who are not afraid to do it openly. They don’t fear being judged by those who believe that crying is a female trait.

There we are, then. Whether one believes in such notional theories or not, without a shadow of doubt, I’m sure if four of us friends in the autumn of our lives were to see Dosti together again, we’d be howling with tears. And this would be as much for ourselves, as for Mohan and Ramu, walking the streets of a city in quest for a better tomorrow.

Photographs courtesy Khalid Mohamed.