Meet Arghyakamal Mitra. He is one of the most outstanding film editors in India with around 100 films in his rich and varied portfolio. He has also tucked in a National Award for Best Editing for his outstanding work in the late Rituparno Ghosh’s Abohomaan (2009). He is quite happy within his home landscape Kolkata and has stuck almost exclusively to Bengali cinema. The one thing he knew is that he just did not want to be an engineer, which his family was intent on.

Mitra is warm, accessible and like most technicians who work behind the scenes – literally – unassuming and grounded. He is almost always present at film premieres, easily noticed by his long, grey sideburns and a fitted cap on his balding pate, dressed in Western dapper wear, forever smiling and ready to talk on any subject , not necessarily linked to cinema.

“I was reasonably good at fine arts – drawing, sketching and painting and wanted to join the Kala Bhavan at Santiniketan. But that was not to be because I missed the last date for applying. I was devastated but I could not confess this to my parents who thought I was doing engineering, which I had joined but did not ever go to college,” says Mitra with a chuckle, going on to say that he did feel guilty but could do nothing about it. “I also visited the painter Ganesh Haloi, who lived in the neighbourhood to request him to teach me. He said he could not teach me but would take a look at my work and make suggestions. That is when the idea of Kala Bhavan came to me. But destiny nullified that too.”

Recalling his first ever brush with watching a film is rather blurred. ” I do remember, however, the film was Erich von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives (1922). The occasion was silent film festival at Sarala Ray Memorial Hall. The year was 1967/68, I think. Not finding a suitable babysitting place my parents brought me along with them. Surrounded by grown-ups, I was constantly shifting in my seat to catch a glimpse of what’s happening on screen. It was black and white and had a lot of writings which I thought I understood. The familiar and comprehensible ones were ‘The’, ‘are’, ‘but’. ‘An’, etc. Then sometime later came the most enjoyable movie experience, The Sound of Music (1965). And somewhat after, came my summer interludes with the Children Film Festival held every year during summer vacations for about a week or so.”

Explaining what pulled him to films, Mitra says, “When I was in my eighth or ninth grade, my interest in cinema started brewing. Thanks to Doordarshan, I was exposed to Charlie Chaplin, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak and various other filmmakers. But it was Ray’s multidisciplinary brilliance that appealed to me the most. He became an icon to look up to. Before I could see his whole range of cinema, I started reading about them. In particular, his Pather Panchali and Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne created a tremendous impact on me. His wrings on cinema in Bengali and English seeded the initial thought – why not be a filmmaker? As the years rolled by, I kept watching a whole lot of films (Indian and international) through gatecrashing various film society screenings, and reading highly engaging books and periodicals on cinema available at the then USIS library. It had a free access reading room and was open to all and sundry during the week days. During this period, I also got deeply interested in Western classical music, Indian classical music and American folk music and I must say that all this impacted greatly on my later work as an editor. My elder brother, who was doing his Economics Honours at Presidency, encouraged me in all my pursuits, specially watching films.”

He adds that growing up in Calcutta helped him greatly in later days in his career in films. “During my impressionable years, Calcutta offered the richest exposure to the best in Indian and world cinema. I lapped them up as much as I could. Attending film festivals, reading on various films and filmmakers, attending open seminars – I was the wide-eyed all devouring cinema buff.”

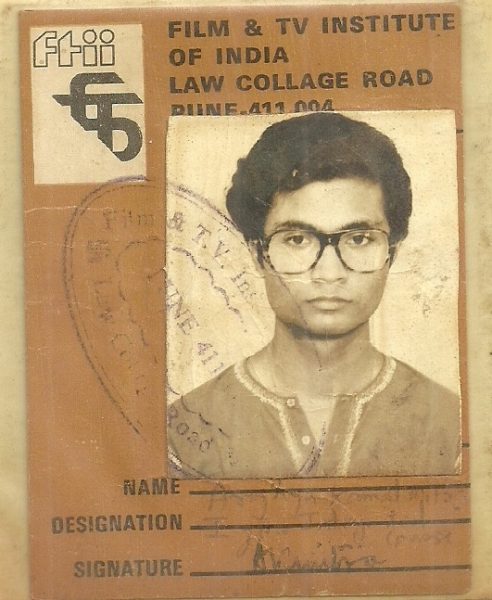

In 1983, Mitra chanced upon an advertisement in the newspaper inviting applications for admission to the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune. He applied without the knowledge of his parents and when the call for the test came, he had to come out with his secret. He went to Pune, where his older sister lived, and stayed on for three months till the FTII began its new session since he had cleared the entrance test, much to his surprise.

But what pushed him to choose film editing at the FTII to train in? To this, Mitra says, “While I was devouring books and periodicals on cinema, I came across several references to editing and its importance in cinema. I had already read The Liveliest Art and When the Shooting Stops the Cutting Begins. The first one talks in detail about editing in Battleship Potemkin (1925). The more I read about editing, the more I got curious about it, as I could not liken it to anything I knew. This intrigue focused my attention more on this discipline. The closest analogy was magic which always fascinated me. So, when I applied for FTII, I knew I had to learn this mysterious aspect of cinema known as editing. Frankly, I had no idea of editing in the real sense. It was a sense of mystery that prompted me to choose this field of filmmaking.”

And what was life at FTII, where he studied from 1983-1986, like? “I think they were the best three years of my student life. FTII was a dreamland. I joined with a sense of wonder and it carried on till I walked out of its portals after my three-year stint as a film student. I was like a sponge soaking in every little experience that came my way. I was in awe of the whole process of filmmaking and was happily sucked into it. Getting barraged by such a huge variety of films from all over he world was an experience unto itself. It was heady.”

He goes on to add that it is very difficult for him to point out which particular films that he watched at FTII impacted on his work as an editor because, “I was too naive to form any concrete opinion on any film. Teachings in my discipline also did not let me choose any particular film or a filmmaker to be my favourite. Entirely my fault perhaps, but I was happy with that. The whole wide world of documentaries, experimental films, underground films and various kinds of fiction narratives (Indian and international) drowned me. Actually, I did not want to perhaps make any conscious effort to stick to a genre and follow it. The films we were exposed to were mostly made by the masters and it’s difficult to choose from them.”

After graduating from the FTII, the world of work had both its good and bad sides. “When I graduated from FTII, it was boom time for television. There was more work in Calcutta than one could handle. But it was all on video. Film work was hard to come by. I was pretty deep into the video world busy making a living. And being a freshly minted film school editing graduate, I was also taken to shoots to provide that extra editorial edge. I happily did that as it also gave me a good exposure of the shoot politics and an opportunity to travel. But I/we (the institutewalas) had to swim through a lot of petty politics that were designed to thwart us from making much headway into the film-industry. So, it was neither the best of times nor the worst of times.”

But in reality, Mitra did not find it tough to land his first job. And that too, as an independent editor for an advertisement film directed by Raja Dasgupta within a week of his coming back to Calcutta. “But it took eight long years for me to land my first ever feature film. I filled in this gap with lots of work for television and video. I slowly realised that I would never get a film work from regular filmmakers. The only way I could land a film work was if the film was directed by one of the directors I had worked with in the video world. Malay Bhattacharya, with whom I had worked on in his television serial, was gearing up to produce and direct his first feature film. It was an FTII meet of sorts. Cinematography was done Sunny Joseph. Sound was done by my FTII batch mate Chinmoy Nath. And edit yours truly. The film went on to win the National Award for Best Debut Film of a Director at the 43rd National Film Awards. It was called Kahini (1995).”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=csKXg3N1hvk

Mitra states that the shift from Steinbeck to Video to Non Linear Editing (NLE) platforms was not difficult for him. “Machines and technologies are supposed to undergo paradigm shifts, but an editor should remain unruffled by them. It should not affect the inner workings of an editor. To me, it is like different kinds of rushes from different directors for different films.”

What criteria does he apply while accepting an editing assignment? Mitra is lucid in is explanation. “First, the cinematic possibility. Second, the narrative plausibility and the third, financial viability. But, as in a non-linear structure, not always in the same order. Most of the time, when the first two work out well, the third fails miserably.” But once he is on board, “I make it a point to understand the demands of the script, the director’s expectation from the film (structure, look and feel, etc.) and my own reading of the film. I make notes of my suggestions, understandings, observations (both positive and negative) and try to have a free-flowing no-holds barred frank discussion with the director. I do not talk about the edit pattern, as I feel that may unnecessarily bog the director down. I try and develop the edit pattern once I get my hands on the rushes.”

About his work along with the director, he explains that he has never worked in the film-school kind of shot breakdown scenario. He prefers to keep away from the floors when a film he is going to edit is being shot. “I like to interact with absolute unknown material and strike a happy friendship in the course of time. But dropping in once in a while to join the fun is always on the cards.”

He explains in meticulous detail, the process of how he makes the first cut of the film and then goes on from that point. “After the synced and scene-wise assembled rushes come to me, I watch them all, the NGs as well. Then I start doing my first cut according to the script. I prefer my director’s absence during this phase. I prefer to work in solitude during this time, because I do not want any interference when I am befriending an unknown entity. Secondly, I do not want any biased opinion to colour my judgment of the material. Once I have come to terms with the material and its first shape, I engage with the director. By this time I already have formed an opinion of the film’s flow, have concrete suggestions on various improvement possibilities, which I share with the director and try and understand his or her viewpoint. I find this approach beneficial for the film and acceptable by most directors.”

Asked to pick out his personal favourites from the 100-and-odd films he has edited over the past 20 years, Mitra says, “Most of Rituparno Ghosh’s films have lived up to their cinematic possibilities. I have edited all his films except two. Then there’s Anup Singh’s Ekti Nadir Naam (2003), Malay Bhattacharya’s Kahini, Suman Mukherjee’s Herbert (2005), Anik Dutta’s Bhooter Bhabishyot (2012), Bauddhayan Mukherjee’s Teenkahon (2014), Aparna Sen’s Paromitar Ek Din (1999) and quite a few more.” He adds that even if he dons the directorial hat in the future, he will never stop being an editor.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Kq0kLS_4N4

Asked to mention memorable sequences he feels he managed to give an extra life to outside the script and the way it was shot, he mentions “some sequences in Kahini, Abohomaan, Chitrangada (2012) and Open Tee Bioscope (2015), to name a few. His National Award citation for Abohomaan says the film’s editing was awarded “For a very precise juxtaposition of time and space, allowing every frame to unravel the story with a keen sense of rhythm and pace.” However, Mitra declares, “What drives me is the work, which is rewarding unto itself. Awards, if they happen are welcome.”

And on that note, we end.