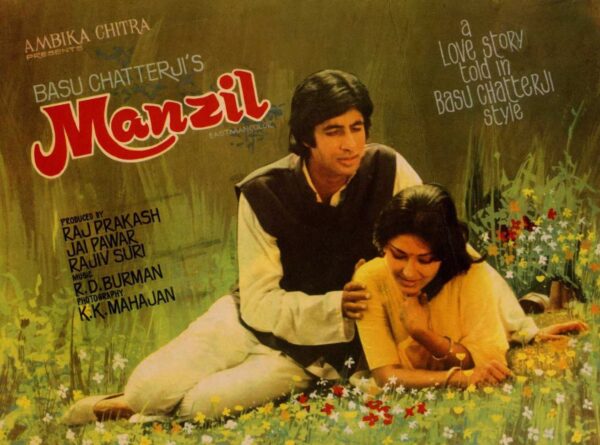

He wouldn’t react to a lousy review by me in The Times of India, except for one occasion. I had pointed out that his film, Manzil (1979), with Amitabh Bachchan and Moushumi Chatterjee, had a pretty similar plot to Mrinal Sen’s Bengali film, Akash Kusum (1965), with Soumitra Chatterjee and Aparna Sen, about a low-rung middle-class white collar workeraspiring to crash by any means into the corporate world. “Tell that boy,” he had sent word, “that he’s written pure nonsense. He should not be permitted to write reviews anymore.” That was so uncharacteristically vindictive of him. A week later, word came again, “Tell him not to get upset with me. I shouldn’t have reacted that way.” That was Basu Chatterji (1927-2020). His fourth death anniversary passed by quietly on June 4. His daughter, Rupali Ghosh, reminded us of the day through social media with memorabilia, photographs and that was that.

Chatterji was born in Ajmer to a Bengali family. He was one of the filmmakers from the Bengali School, as it were, who was a major force in his own individualistic way within the Bombay film industry — just like the redoubtable Bimal Roy, Asit Sen, Shakti Samanta, Satyen Bose, Dulal Guha, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Anil Ganguly and Basu Bhattacharya, all of whom had their separate distinct styles and thematic concerns.

More prolific than most, Basuda helmed forty-one films in Hindi and Bengali, and as many as eight TV series, stamping his seal on stories revolving around little big people of the rising social strata, described somewhat facilely as the middle class. I say facilely, because within this class there were sub-stratae, be it a landed family on its last legs, the unemployed or the more secure white collar workers.

This remembrance is belated, yes, but for me it’s important to recall him for a personal reason: he was my mentor (though I never told him that) and a gateway to world cinema since he was one of the chief pilots of the strong film society movement dominant.

From the minuscule library of film-related books at the office of the film society, Film Forum, besides Dadar Railway Station, he would press upon me volumes of studies on the great directors be it of Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa or Satyajit Ray, and of the critics – Andrew Sarris, Penelope Houston and Pauline Kael, to cite random examples. “Return what you borrow within a week or a fine will be imposed on you,” he’d stay strictly but would ignore the stricture if I ever erred which was quite often.

On being asked why at times he spelt his surname as Chatterji instead of the usual Chatterjee, he had laughed lightly, “You do ask inane questions. Both ee and i are fine by me.”

As Basuda advanced in years and was largely housebound, monthly visits to his first floor apartment in a tree-shaded lane of Khar-Santa Cruz building were a must. His wife would retreat into another room or to the kitchen to rustle up tea and pakoras for snacks. And he would often ask me, as seriously as magistrate, “Why don’t you remake Rajnigandha (1974)? It’s still relevant. I won’t charge you except for a bottle of Black Label Scotch. Do make sure it’s not fake stuff.”

Once, he whipped out a script from his desk’s drawer titled The Window about a cloistered Muslim girl, who’s romanced by a stranger on a motorcycle. He waits on the street below her house’s window till she waves back to him every day and accepts the roses he flings to her. She’s attracted to him, their marriage is finalized, which means that her Dubai-based brother has to make it to the wedding ceremony. He does so reluctantly only to be arrested by the groom-to-be, an undercover police officer , who had conned the girl so he could arrest the brother, suspected to be working with a mafia syndicate. The girl never opened her window again.

“This script is for free. Just do a good job of it, no item numbers please,” he had said sombrely. Regretfully, I could never raise funds to make it. ‘Muslim’ stories were and still are considered risk-prone by the film trade cash bags. On facing an impasse, I asked Basuda if I could edit the script and use it with his byline in a compilation of short stories titled Faction. His disappointed response was, “Do people still read books? Anyway I’ve given it to you. Just send me a copy of the book whenever it’s published.”

Clearly, Basuda was still itching to make yet another film himself, on half a shoestring budget if needed. And despite his deteriorating health, he would often take off to Kolkata to confect a Bengali film, which required neither outlandish finance nor brain-curdling plots. At the age of 93, he had retreated into himself but still had countless stories to tell of the people he knew best – upright men and women in a big city buffeted by plausible crises, which were overcome with honesty and humor. No French-bearded baddies, cigarillo-puffing vamps and stunt-addicted superheroes marred his oeuvre of feature films not to forget those vintage, trend-setting TV series: Rajani (1985) showcasing a firebrand housewife and Byomkesh Bakshi (1993) following the adventures of a Sherlock Holmes-like sleuth.

Garbed in a navy blue lungi, bare-chested (unless an unfamiliar visitor was expected) and relishing his evening quota of blended Scotch whisky (“Single malt-valt I don’t like”), Basuda couldn’t ever reconcile himself to the notion of semi-retirement. “I keep doing small films whenever a financier is interested,” he would shrug in a study equipped with a state-of-the-art computer. “I surf the Internet,” he continues. “There’s so much going on. Making films on high definition is everywhere (the streaming giants like Netfilx were still to arrive). Just one digital film, blown up to 35 mm has to click in a big way in the Mumbai film industry, and everyone will be running towards the medium. It’s here but hasn’t become as strong as it has in the West.” The entries at the Berlin International Film Festival three years ago, he recalled, were largely digital.

He was amazed, that even the Hollywood blockbusters like Avatar (2009) had opted for digitally enhanced visuals. But beyond a point, conversations on techno-flash, bored him. Frequently, I would wonder why he hadn’t agreed to an authorised autobiography, hinting that I would be grateful to do it. Pouring us Patiala pegs, he would grin wryly, “A book? Forget it. I would have to lie through my teeth, say I’m nice and everyone has been nice to me. I’ve always hated politically correct biographies. They don’t inform readers about what they don’t know already. Who needs that?”

I’d argue that he’d been a professional cartoonist and illustrator with the weekly tabloid, Blitz, and had been on the frontline of the Film Society Movement since the mid-1960s. For the book, Basuda could surely dwell on topics that weren’t personal or gossipy. To that, he’d retorted that not many would be interested. “Film societies, aah! That era has gone. And look at the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC), either dead of making rubbish.”

The 1960s and the beginnings of the ‘70s were the time to crusade for better cinema and to expose viewers to world cinema. The snow-haired stalwart would insist: “Screenings of short films from the Oberhausen festival in Germany, a collection of Czech films and the French New Wave masterpieces were jampacked and in fact, have influenced so many of our quality-conscious Indian film directors. Digital has ruined everything from what I hear, downloading any film from any part of the world. People don’t travel miles to see rare masterworks anymore – like they would for the morning shows of Satyajit Ray films at the Chitra cinema in Dadar.”

Trusting two callow students from St Xavier’s College – Abbas Abbas and me, Basuda had asked us to take over the editorship of Film Forum’s quarterly magazine Close-Up. We were over the moon – writing, commissioning and I dare say finessing articles, imagining up headlines, ferreting photographs and placing every issue for two years to bed at a darkly-lit Byculla printing press, never once missing a deadline. The Forum’s members were pleased with the outcome, earning ‘shabashes’ even from the then Times of India critic, Bikram Singh. And then Abbas in a fit of independence, penned an article on the seasoned writer, filmmaker and social activist, KA Abbas, calling him ‘mediocre’ and a ‘charlatan’.

Basuda was furious. Our apprenticeship, at a token fee, was over and the magazine went back to an office-bearer of the Film Forum. Gratifyingly, we weren’t exiled from the Film Society. In private, Basuda told us, “You guys did nothing wrong. It was your opinion. But you know how it is, the majority of the editorial board voted against you and called you irresponsible kids.”

That was a learning experience for me, vis-a-vis the career in journalism I would eventually opt for. Write what you truly feel and if there are repercussions, take them in your stride. Anyway as it happened, the office-bearer couldn’t handle the extra work burdened on him. Abbas and I were back at the Byculla printing press, chastened but wiser, and continued to bring out our baby, Close-Up. Sadly, Abbas Abbas passed away just before college graduation of a sudden ailment. I asked politely to withdraw from the responsibility of Close-Up.

While spearheading the Film Forum society along with the Arun Kaul, Basuda had begun working on his debut black-and-white film, Sara Akash (1969), which delved into a young man’s resistance to an arranged marriage. It drew much praise from the mandarins. As for producers and distributors, they woke up to the director’s brand of intimate films, which could make cushy profits. And did so five years later with the sleeper success of Rajnigandha (1974). This little gem looked at the dilemma of a young woman (Vidya Sinha) dilemma in choosing a life with a mousy middle class clerk (Amol Palekar) or a city slicker (Dinesh Thakur) How can the mouse walk away with the heroine towards a comforting, happy ending, was the question.

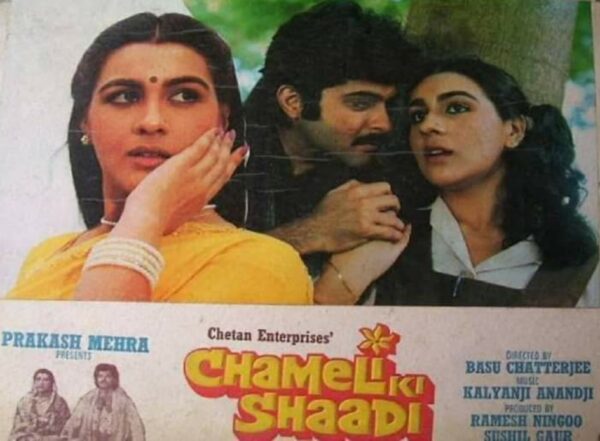

Chhoti Si Baat (1975) and Chitchor (1976) sided with the awkward simpleton over the diametrically contrary suave man-about-town. Intermittently, there’d be no denying that Chatterjee took on more on his plate than he could chew, resulting in the sub-standard Us Paar (1974), plagiarised from a Czech film, Romance for a Bugle (1974), Safed Jhooth (1977), and Do Ladke Dono Kadke (1979). Yet the director, after the downers, would bounce back with Priyatama (1977), Swami (1977), Khatta Meetha (1978), Baaton Baaton Mein (1979), Apne Paraye (1980), Shaukeen (1981) and Chameli Ki Shaadi (1986).

Quizzed about the film which was the closest to his heart, he’d immediately answer Jeena Yahan (1979), a barely remembered, uncompromised take – enacted by Shabana Azmi and Shekar Kapur – on a young couple’s adjustment to the rigours of urban pressures. Of his favourite actor, he’d say Amrita Singh in Chameli Ki Shaadi, adding that her spontaneous performance had bowled him over.

Inevitably, Basuda’s films have been compared with those of Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s for their modest budgets, solid storytelling and with time, accomplished performances from the top stars of the time including Rajesh Khanna, Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan and Jaya Bachchan nee Bhaduri. Monitor them closely, though, and both the auteurs reveal their separate signatures. Hrishida was fulsomely sentimental and emotive, Basuda more bemused and casual.

Incidentally, there has been scant if any exposure of Basuda’s last Hindi films – Prateeksha (2006), featuring Jimmy Sheirgill and Dia Mirza, and Kuch Khatta Aur Meetha (2007) with newcomers in the lead supported by Anupam Kher and Moushumi Chatterjee. “Don’t ask me why, ask the producers,” would be his terse response whenever I mentioned them.

Towards his end-years, I was determined to make a documentary albeit on a zero-budget, on his body of work. A team of videographers volunteered to work free of charge. However, it was much too late. Our first afternoon session at his home, merely drew monosyllabic answers. He was uneasy and couldn’t fathom why we had encircled him with technical paraphernalia. The documentary was eventually abandoned.

Much before that afternoon when we shot with him, I’d wished to know whether the champion of the everyday man’s ethos ever sat back and watch re-runs of his films on television? “Never!” was the answer. After the third Patiala peg, he’d scratch his ears as was his habit and emphasise that he would like to take off for the next Indian International Film Festival, wherever it was happening — Goa, Thiruvananthapuram, Kolkata, Delhi, wherever, That said, he’d clink crystal glasses, “Till then here’s to my next film – whether it happens or not. Cheers!”

Header photograph of Khalid Mohamed with Basu Chatterji courtesy Khalid Mohamed.