It was a strange and difficult time. The Covid-19 pandemic had engulfed the world and one was caged in one’s typical matchbox apartment in the megapolis that Mumbai is. The empty roads and clear blue sky seemed dystopian in a city that never slept. One way to beat all this was, of course, watching films. Along with my group of friends, I started to discover masters hitherto unseen, like Samuel Fuller and Agnès Varda, whose films for some reason I had hardly seen. They were a revelation for me, not just for their cinematic aesthetics but more importantly, reawakening a ray of hope that good films could be made without investing mega bucks. Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave cracked this pretty early, Varda being a fine example. As I watched more and more films, I returned to a filmmaker who is very dear to me and quite simply a phenomenon in his own right, Éric Rohmer! His masterpieces like My Night At Maud’s (1969), Claire’s Knee (1970), The Aviator’s Wife (1983) and Pauline At The Beach (1983) opened many mental blocks we film school graduates, in particular, carry. I was itching to make another film since my previous one, Ek Betuke Aadmi Ki Afraah Raatein, which had its theatrical release in the September of last year, and Rohmer and Varda cracked the code for me. I thought why not make a walking-talking film the way Rohmer loved to do?

As the idea began to take root, I revisited my days at the Film & Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune as a student. The urban youth in our cosmopolitan cities deal with similar problems and anxieties as any young population of the Western world. But what makes us different is our acceptance of the inevitable and transcendence, which are essentially Eastern beliefs. Keeping that in mind, I started to flesh out the characters of four youngsters in their mid to late twenties – two in a traditional relationship for a bit and two who hook up on and off – who plan a weekend trip from Bombay (now Mumbai) to nearby Khandala at a homestay run by a middle-aged lady. Truth be told, all these five characters were modelled after someone or the other I know. The script followed rather effortlessly once the characterizations and their relationships were clear.

Now came the real difficult part, or so I thought, getting the film off the ground. I had to convince my cast, the crew and the owner of the bungalow I wanted to film in to become good Samaritans. Lo and behold they did! And so, the film was on its way!

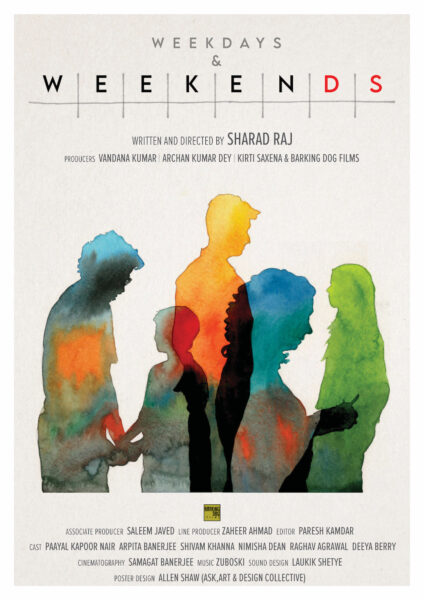

Weekdays & Weekends takes a leaf out of the films of the French New Wave in terms of its form and aesthetics but adapts it for our purposes here. Agnes, Eric (yes, my homage to Varda and Rohmer), Aakil and Shahana urf Sherry are friends working in Mumbai when they decide to go for a break where Aakil meets Tapti the homestay owner. Their relationships, desires and fidelities are put to test over the weekend before they return to Mumbai on Monday. The film dwells quite nonchalantly on whatever transpires between the principal characters through small interactions like walking, sitting, and talking. As their anxieties come to the fore, they introspect on their lives. But whether they leave wiser or not is never explained. Perhaps, they just leave in a state of flux that can go either way. The film never points to any sort of definite ending though the events do culminate in a climax of sorts.

The choice of the bungalow, naturally, was critical. Sukoon Bungalow in Khandala, where I shot the film, had immense possibilities in terms of its ups and downs, dynamic angles and exterior lawns with the forest area behind. This made my task simpler for though I was in a solo location, I knew I could go far beyond the ‘four walls’ the bungalow offered me. During the technical recce, my Cinematographer or DOP, Samagat Banerjee, and Chief Assistant Director, Aryan Singh, and I blocked all the scenes room wise as well as those scenes outside of the bungalow as well. We had just 5 days to shoot the whole in Khandala and then a day in Mumbai, so our prep and planning was critical. I had told Samagat, “No lights!”, so he made do with just some Chinese lamps and 4 RGB Godot lights. The three of us explored every possible angle in the bungalow keeping in mind that it should give an expansive feel despite being a single location. I think we succeeded because later at a closed door preview of the film, the owner of the bungalow, Nasreen Contractor said,” I had no idea my bungalow has so much variety to offer!”

Like I said, our prep was critical. Following the technical recce, Samagat made a mood board of the entire film in terms of lensing, framing and lighting. I was amazed how extremely meticulous he was knowing that he had an extremely difficult task at hand with minimal lights. It is to his credit that not only did he deliver, he got a huge pat on the back from a brilliant DOP like Rafey Mahmood, no less.

I then cast for the film and began to rehearse with the actors. My approach to acting is observational wherein the camera stays away from the characters at a distance, most of the time just ‘observing’ the action. Meanwhile, my brief to the actors was simple. “Just be yourself. The character must become you and not the other way round. You have the freedom to walk and talk the way you want to, just don’t be in a rush or else it will appear as if an actor wants to deliver his or her lines.”

When a revered mentor to some of the best films made in India, Paresh Kamdar (also my senior from the FTII), saw the edit lineup, he was quite pleased overall with the scheme of things. He did suggest that it would help the film immensely if I add more shots of the jungle for Sherry to wander in. So, we shot for another day at the Borivali National Park in Bombay with Nimisha Dean, who plays Sherry in the film. And then Paresh did the final edit. The biggest advantage of having someone like Paresh edit the film is that we both have a similar approach to rhythm and tempo. And Paresh doesn’t simply edit the footage according to the script but constructs the film from scratch from the footage shot. For the first time in my life, I understood what Robert Bresson meant when he said, “The film dies at the edit table.”

I was extremely fortunate to have a sound designer like Laukik Shetye whose delicate work had impressed me as a student. Following the shoot, Laukik revisited the location in Khandala and recorded about 8-10 hours of ambience sounds. Mentored by his faculty, Bhasker Roy, he adhered himself to a very minimalist soundtrack for the film, choosing one signature sound for each room. When Bhasker mixed the film, one realized why he is such a sought-after Mixing Engineer. He is not a technician but a poet when it comes to Sound Engineering! In this day and age, where films in multiplexes are blaring with extreme loud-in-your-face sound designs, Laukik and Bhasker’s approach came as a refreshing breath of fresh air.

Weekdays & Weekends is made at a modest budget of 5 lakhs with invaluable support from not only its cast and crew but also the people at Whistling Woods International (WWI), where I teach filmmaking. I cannot thank Head of Academics, Mr. Rahul Puri, and all the students and faculty of (WWI) enough for all their help. The film would also not have been possible without Saleem Javed, my partner and associate producer of the film, and Zaher Ahmed the line producer. They have been a huge, huge support to me since we collaborated together on Ek Betuke Aadmi Ki Afraah Raatein.

Weekdays & Weekends is a humble attempt in making a film with limited characters and filmed by and large in a single location. I hope I have succeeded in telling my story the way I wanted to and the film could be a significant reference for aspiring filmmakers to understand its exploration of space and how the budget constraints and production restrictions can sometimes become an extremely effective tool to explore formal possibilities and arrive at exciting results. The film is now available to view worldwide on the T-VOD platforms of Apple TV (iTunes) and Google Play.