How old is Tamil cinema? When was it born?

An automobile spare part dealer, Nataraja Mudaliar, was so fascinated by moving pictures when he watched them in Madras that he decided to make films himself. He traveled to Pune, sought and met Steward Smith, a cinematographer of the British Government and learnt film making. It took only a few days to learn to handle the primitive camera operated by hand cranking. Returning to Chennai he set up a studio, India Film Company in Kilpauk and made Keechakavatham/The Destruction of Keechaka the first Tamil film in 1916. The characters spoke Tamil: However, sound in film had not been invented yet, so what they spoke was written in cards that appeared on the screen between shots: The viewers, instead of hearing, read the dialogue. For the benefit of those who could not read, a man stood near the screen and read the dialogue aloud. Soon a few other studios were set up in Madras. In the following eighteen years, nearly 110 Tamil silent films were produced.

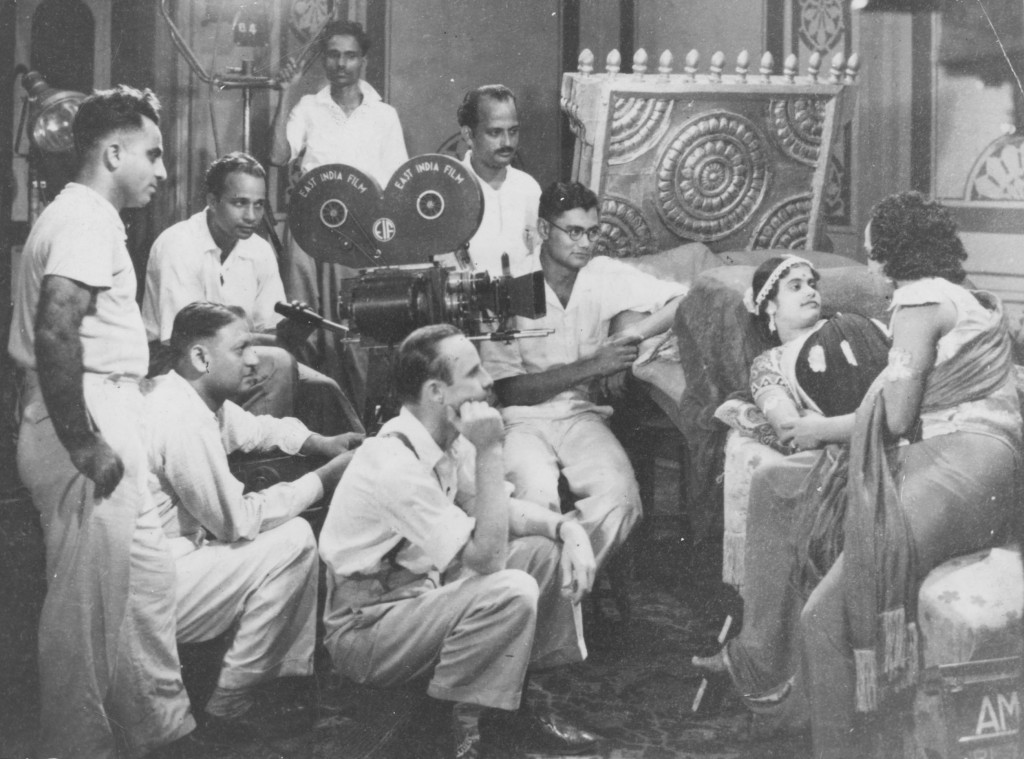

In Madras, there were at least three studios regularly producing films. The leading company was General Pictures Corporation, known as GPC, founded by A Narayanan. It was here that many of the later directors and actors of the talkie era had their initial training. It was a school for filmmakers. Many films were based on stories from the Puranas, like Machavataram (1927). There were also films from folk lore such as Peyum Pennum/The Devil and the Damsel (1930). Some were from the epics, like the film Kovalan (1929). A few socials also came out:the film version of Vai. Mu. Kothainayaki Ammal’s novel Anadhai Penn/Orphan Girl (1931) was directed by the legendary Raja Sandow. These films were reviewed in contemporary Tamil magazines.

No cinema in the world disowns its silent era. That is where the roots of any cinema lie. Every cinema in the world, be it French or German, glorifies its silent films and count its own history from the silent era. Much of Charlie Chaplin’s films, including the classic, The Gold Rush, a silent film are part of American film history. Russian filmmaker Eisenstein’s unforgettable silent film Battleship Potemkin is almost a symbol of Russian cinema. The rules of film grammar were formed during the silent era. It is alike a childhood of a human being.

There were some pioneers in Tamil Nadu who had made ‘short’ films, even before Nataraja Mudaliar’s Keechakavatham. Marudamuthu Moopanar, a land lord from Thanjavur, filmed the coronation of King George V in 1911 in London and screened it in Chennai. When the first airplane landed in Island grounds, he filmed it.

To say that Tamil cinema is 75 years old is not only a mistake but it disowns a precious heritage of the industry. It was the pioneers of the silent era, like Nataraja Mudaliyar, and A Narayanan who laid the foundation for Tamil cinema. Hopefully, when we celebrate the centenary of Tamil cinema in 2016, we will remember these pioneers.

This is great and refreshing. It is nice to read about cinema other than Bollywood and one hopes for many more such informative pieces from you, Sir. It is about time we stopped giving step motherly treatment to our regional cinemas, which often do better work than their Hindi counterparts and are far better rooted as well.

Wonderful to get in touch with you through the language we share – writing on and about cinema. I look at your writing as a learning experience because we know very little about cinema in the South be it Tamil Nadu or Kerala or Andhra Pradesh or Karnataka. It is not that we do not care to know but because there is little perpetuation of this kind of knowledge and information available in the normal course. The information and media highway is filled with Bollywood which, though good, is all sound and little fury. It has the financial and infrastructural network few regional cinema pockets have. Those that do have the money, immediately begin cut-and-paste jobs from Hindi hits. In Bengali cinema, they are even buying copyrights to language version of Kannada, Tamil, Malayalam and other hits. Regional cinema in this sense, at least in Bengal, has almost lost its cultural and ethnic identity. I know as a critic of Bengali cinema today, I am rubbing people up the wrong way but it is the truth and at my age, I do not think we need to shy away from the truth. The intellectual filmmakers who belong to off-mainstream cinema in Bengal do not have mass viewership and they do not seem to care about mass viewership much. Why, I really do not know unless the National Awards and International Film Festivals are their specific targets. This means that they will not be remembered by the masses who would have hardly have seen these films.

Gone are the years of Golden Cinema in Bengal where we had the Uttam-Suchitra screen chemistry enough to set the audience craving for more; educated directors like Tapan Sinha, Ajoy Kar, Arabindo Mukherjee, etc making it to the hearts of the Bengali audience with their mainstream films that were very well made, had solid story lines, good acting and memorable music.

Thanks Theodore, for bringing back golden days of Tamil cinema we all knew so very little about.

Nice informative article on Tamil cinema. Thanks a lot sir, and keep us posted on more such stuff because we – who are not from the South, hardly get to hear about vintage Tamil cinema. Would like to read on Sivaji Ganeshan, MGR, Gemini Ganeshan and other great entertainers and technicians.

I loved the story of the very beginning of Tamil cinema. One man’s passion, and an industry is set up. It would be great to see these silent films. I agree with you totally that they are the roots of what came later.

But is this being disowned in the Tamil industry? Sorry for sounding so ignorant, but I know very little about the Tamil industry. If it is, then it is a shame.

Lucid but very informative article. Eagerly awaiting more such articles on Tamil cinema – perhaps one of the most vibrant and innovative filmmaking industry in India.