“My rebellious notes make the world think that my heart abhors the lyrics of love, that I find solace in strife and war, that my very nature relishes blood-letting, that my world cares not for life’s finer things, that the noise of revolt is music to me.”

These lines, translated from Urdu, were written more than 50 years ago under the title, Mere Geet. They remain largely obscure because they are not among the work their author became more famous for: film lyrics. The above lines — and the reason the poet gives for that state of mind — reflect, however, an important facet of his personality. The author of these lines, Sahir Ludhianvi, was different. Unable to sing hymns to Khuda (God), Husn (beauty) and Jaam (wine), his pen would rather pour out his anguish and bitterness over social inequities, political cynicism, the artificial barriers that divide mankind, the senselessness of war, the domination of materialism over love. His loves, and love poems, were tinged with sorrow, with the realisation that there are stark realities more important than romantic love. This facet was seen in his lines for the film Didi: Zindagi Sirf Mohabbat Nahin Kuch Aur Bhi Hai Zulf-o-Rukhsaar ki Jannat Nahi Kuch Aur Bhi Hai Bhookh Aur Pyaas ki Maari Hui Is Duniya Mein Ishq Hi Ek Haqeeqat Nahin Kuch Aur Bhi Hai. And in Pyar Par Bas To Nahin Hai Lekin Phir Bhi Tu Bata De Ki Main Tujhe Pyar Karoon Ya Na Karoon in the film Sone Ki Chidiya (1958).

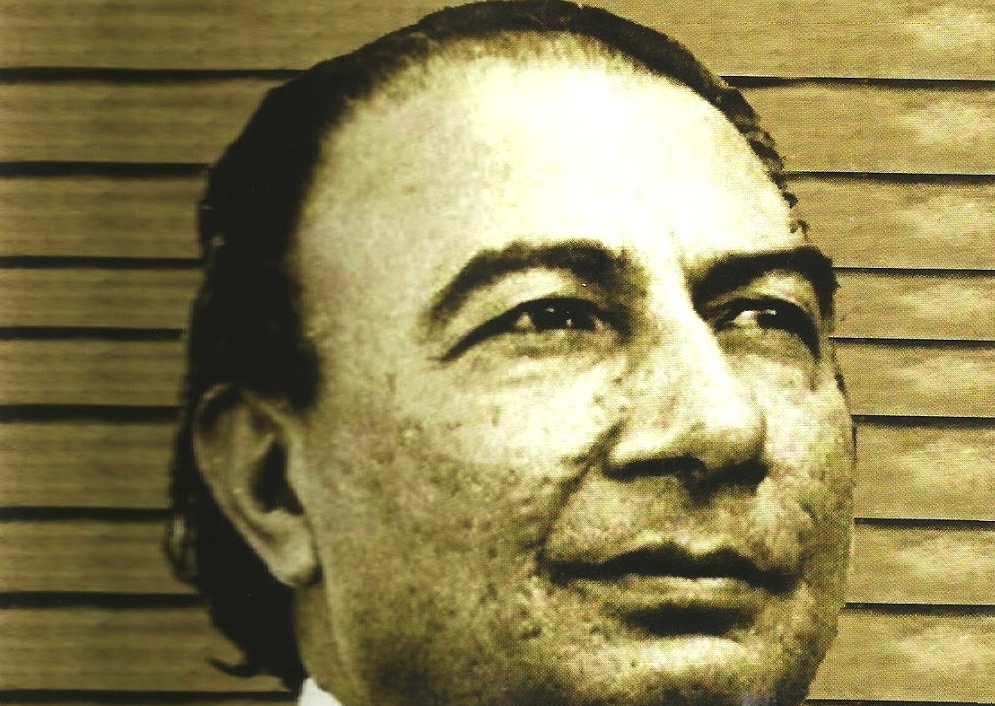

Born Abdul Hayee on March 8, 1921, Sahir was the only son of a Ludhiana zamindar. His parents’ estrangement and the Partition made him shuttle between India and Pakistan. It also brought him face to face with a struggle called life. A member of the Progressive Writers’ Movement, he edited the publications Adab-e-Latif, Pritlari, Savera and Shahrab. An arrest warrant issued by the Pakistani government of the day made him flee to Bombay in 1949. By now, he had managed to publish his anthology Talkhiyaan (Bitternesses). Besides Talkhiyaan and the hundreds of film songs he penned in a career spanning three decades, Sahir also authored the anthologies Parchaiyan, Ao Ki Koi Khwab Buney and Gaata Jaaye Banjara.

Sahir broke through in films in Bombay with his lyrics for Naujawan (1951). Even today, the film’s lilting song Thandi Hawayen Lehrake Aayen makes hearts flutter. His first major success came the same year with Guru Dutt’s directorial debut, Baazi, again pairing him with composer SD Burman. Together, S D Burman and Sahir created some of the most popular songs ever: Yeh Raat Yeh Chandni Phir Kahan – Jaal (1952); Jaayen to Jaayen Kahan – Taxi Driver (1954); Teri Duniya Mein Jeene se Behtar Ho Ki Mar Jaayen – House Number 44 (1955); and Jeevan ke Safar Mein Rahi – Munimji (1955). The duo reached their creative zenith with Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (1957), the very basis of which was Sahir’s poetry.

All good things, as they say, come to an end. SD Burman and Sahir parted ways after Pyaasa and sadly, never worked together again. Sahir, already a stalwart as the 1960s approached, wrote gems for films like Hum Dono (1961), Gumraah (1963), Taj Mahal (1963), Waqt (1965), Humraaz (1967) and Neel Kamal (1968), teaming up with composers Ravi, Jaidev, N Dutta, Roshan, Khayyam, RD Burman and Laxmikant-Pyarelal. Sahir’s work in the 1970s was mainly restricted to films directed by Yash Chopra. Though his output in terms of number of films had thinned out, the quality of his writings commanded immense respect. Kabhi Kabhie (1976) saw him return to sparkling form. These songs won him his second Filmfare award, the first one being for Taj Mahal.

Sahir’s poetry had a Faizian quality. Like Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Sahir too gave Hindustani/Urdu poetry an intellectual element that caught the imagination of the youth of the forties and fifties and sixties. He helped them to discover their spine. Sahir asked questions, was not afraid of calling a spade a bloody spade, and roused people from an independence-induced smugness. He would pick on the self-appointed custodian of religion, the self-serving politician, the exploitative capitalist, the war-mongering big powers. Aren’t they familiar? Close to Sahir’s heart were the farmer crushed by debt, the young man sent to the border to fight somebody’s dirty war, the lass forced to sell her body, the youth frustrated by unemployment, families living in dire poverty… The underdog remains; his bard is gone.

Whether it was the arrest of progressive writers in Pakistan, the launch of the satellite Sputnik, or the discovery of Ghalib by a government lusting minority votes, Sahir reacted with a verve not seen in many writers’ work. Kahat-e-Bangal (The Famine of Bengal), written by a 25-year-old Sahir, bespeaks maturity that came early. His Subah-e-Navroz (Dawn Of A New Day), mocks the concept of celebration when the poor exist in squalor.

Writing for films occupied much of Sahir’s time and energy in and after the fifties. Never one to compromise while writing for a “lesser” medium, Sahir wrote such evocative songs like Aurat Ne Janam Diya Mardon Ko, Mardon Ne Use Bazar Diya for Sadhna (1958) and Tu Hindu Banega Na Musalman Banega, Insaan Ki Aulad Hai, Insaan Banega for Dhool Ka Phool (1959). Then who can ever forget Yeh Duniya Agar Mil Bhi Jaaye To Kya Hai or Jinhe Naaz Hai Hind Par Woh Kahan Hain from Pyaasa? Pyaasa, a movie that many suspect was his biography, was the high point of Sahir’s genius. By now, Sahir was also disillusioned over the state of the nation following the first decade of Indian Independence. His dissatisfaction with Congress policies found voice in songs like Jinhe Naaz Hai Hind Par Woh Kahan Hain and Chino Arab Humara – Phir Subha Hogi (1958). This combination of political awareness and humanitarian compassion is found all through in Sahir’s poetry, whether written for films or not.

Ever a sensitive soul, Sahir reacted to the world around him, pouring his sentiments into the songs he penned for films. Coming from his pen, even the most mundane song would have a message. For example, this song from Neelkamal: Khali Dabba Khali Botal Le Le Mere Yaar Khali Se Mat Nafrat Karna, Khali Sab Sansar. His poetry could at once be sublime – Tora Man Darpan Ehlaye Bhale Bure Sare Karmo Ko Dekhe Aur Dikhaye from Kajal (1965), introspective – Man Re Tu Kahe Na Dheer Dhare from Chitralekha (1964), invoking divinity – Allah Tero Naam Ishwar Tero Naam Sabko Sanmati De Bhagwan from Hum Dono, esoteric – Khuda-e-Bartar Teri Zameen Par Zameen ki Khatir Jung Kyon Hai from Taj Mahal, and philosophical – Jahan Mein Aisa Kaun Hai Ki Jisko Gham Mila Nahin again from Hum Dono. There lay Sahir’s spirituality. Ingrained in this spirituality was a quest for a greater humanity, better people, a livable world. Paradoxically, it always involved, and was about, the material rather than the metaphysical.

A colossus among song writers, Sahir fought for, and became the first film lyricist to get, royalty from music companies. He would deeply involve himself in the setting of tunes for his songs. Any wonder why they are extra melodious? There was a negative trait too: Sahir would insist he be paid a rupee more for each song than Lata Mangeshkar was. Call it a left-over of his zamindar background, or an example of success gone to the head, this egotism of Sahir has been heard of and written about.

A bachelor to the end, Sahir fell in love with writer Amrita Pritam and singer Sudha Malhotra, relationships that never fructified in the conventional sense and left him sad. Ironically, the two ladies’ fathers wouldn’t accept Sahir, an atheist, because of his perceived religion. Had they seen the iconoclast in him, that would have been worse; being an atheist was worse than belonging to the ‘other’ religion. Sahir, perhaps, had an answer to such artificial barriers in these lines written for Naya Rasta (1970): Nafraton Ke Jahan Mein Humko Pyaar ki Bastiyan Basani Hain Door Rehna Koi Kamaal Nahin, Paas Aao Toh Koi Baat Bane.

A young Amrita Pritam, madly in love with Sahir, wrote his name hundreds of times on a sheet of paper while addressing a press conference. They would meet without exchanging a word, Sahir would puff away; after Sahir’s departure, Amrita would smoke the cigarette butts left behind by him. After his death, Amrita said she hoped the air mixed with the smoke of the butts would travel to the other world and meet Sahir! Such was their obsession and intensity.

Sahir died after a heart attack he suffered while playing cards on October 25, 1980. One suspects the poet, whose heart bled for others, never paid enough attention to his own life. There was a card-player nonchalance about himself, as seen in this Hum Dono song: Main Zindagi Ka Saath Nibhata Chala Gaya Har Fikr Ko Dhuein Mein Udata Chala Gaya… Decades after his death, his songs remain immensely popular. His poetry continues to inspire radical groups and individuals and strikes a chord in sensitive people, leftist or not. Why else would a Vajpayee invoke Sahir while taking a dig at Pakistan? Woh Waqt Gaya Woh Daur Gaya Jab Do Qaumon Ka Naara Tha, Woh Log Gaye Is Dharti Se Jinka Maqsad Batwara Tha…

Had Sahir not allowed drink and cigarette smoke to consume himself, had he lived a fuller life like contemporaries Majrooh Sultanpuri and Kaifi Azmi did, it would have been interesting to watch him react to changing social values, to politics touching its nadir, to ‘secular’ becoming a dirty word, to the abuse of religion to spread hatred and get votes, to the supposed failure of communism, to the never-ending dowry deaths, to the intellectual inertia of the intelligentsia…. Perhaps he would have influenced thought as he did in the past. Maybe his message to the masses would have been the same as it was decades ago: Tumse Quwwat Lekar, Main Tumko Raah Dikhaoonga Tum Parcham Lehrana Saathi, Main Barbat Par Gaoonga. Aaj Se Mere Phan Ka Maksad Zanjeeren Pighlana Hai Aaj Se Main Shabnam ke Badle Angaare Barsaoonga (Drawing from your strength, I shall show you the way you wave the flag, comrades, I shall sing for you, my art will now melt your chains From now on my poetry will rain embers).

This is absolutely beautiful.

Like poetry.

I couldn’t have imagined a more poignant ode to a legend than this.

Mesmerized by the writing.

Wow.

Just wow.

Completely Jawad Daud’s thoughts on reading this.

I meant completely echo his thoughts.