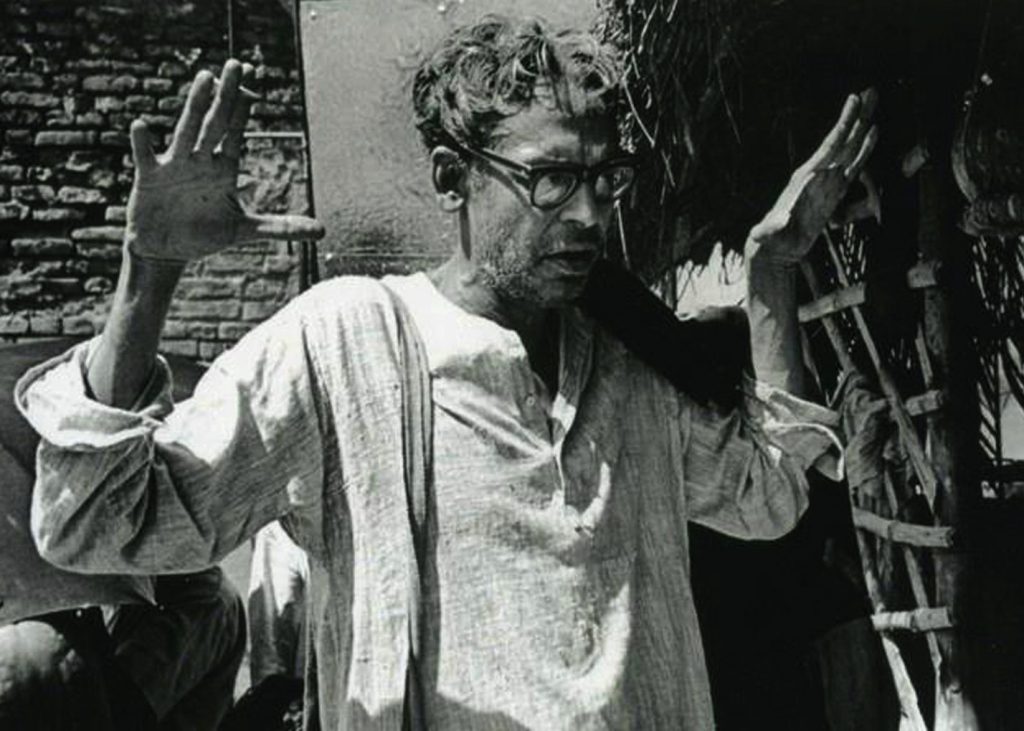

It is one of life’s greatest ironies that Ritwik Ghatak who is today something of a cult figure in Bengal was so little understood and appreciated during his lifetime. Today, his films have won much critical acclaim but the fact remains that in their time, they ran to mainly empty houses in Bengal. It’s a huge tragedy because Ghatak is an auteur whose films project a unique sensibility all of his own. Though it has to be said, they are often brilliant, but almost always flawed as well.

A contemporary of both Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen, Ghatak was born in Dhaka now in Bangladesh on November 4, 1925, one of nine children. His family moved from Berhampore, Murshidabad and then finally to Calcutta (now Kolkata). Calcutta saw a flood of refugees in this period, first to escape the horrific Bengal Famine of 1943, and later on the partition of India. In fact, the partition of Bengal, the division of a culture, was something that haunted Ghatak forever and would feature repeatedly in his work revolving around two central themes: the experience of being uprooted from the idyllic rural milieu of East Bengal and the cultural trauma of the partition of 1947.

Ghatak wrote his first play, Kalo Sayar, in 1948. He then joined the left-wing Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) where he worked for a few years as a playwright, actor and director. During this period, He wrote, directed and acted in plays and even translated works by landmark playwrights Bertolt Brecht and Gogol into Bengali. When IPTA split into different factions, Ghatak turned a greater part of his attention to filmmaking.

Ghatak had already got his introduction to filmmaking in 1950 itself with Nimai Ghosh’s Chinnamul, where he doubled as an actor and as an assistant director. He then began his first film, Nagarik (1952). The film is about a young man’s search for a job and the erosion of his optimism and idealism as his family sinks into abject poverty. Sadly, the film could not release at the time of its making and finally made it to the theatres in 1977, a good 25 years later, and after the death of its maker in 1976.

Ghatak accepted a job with Filmistan Studio in Bombay in the mid 1950s but his ‘different’ ideas did not go down well there. He did, however, write the scripts of Musafir (1957) and Madhumati (1958) for Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Bimal Roy respectively, the latter becoming an all time, evergreen musical hit with an extremely clever climax in which the ghost gives the villain his comeuppance.

Ghatak returned to Calcutta and made Ajantrik (1958) about a taxi driver in a small town in Bihar and his vehicle an old Chevrolet jalopy. An assortment of passengers gives the film a wider frame of reference and provided situations of drama, humour and irony. The film, an early attempt in an Indian film to use an inanimate object as a character, was shown at the Venice Film Festival in 1959 and preceded the Herbie films that came from hollywood. Film critic Georges Sadoul, who saw the film at the festival, remarked, “What does Ajantrik mean? I don’t know and I believe no one in Venice Film Festival knew…I can’t tell the whole story of the film…there was no subtitle for the film. But I saw the film spellbound till the very end”. That year, Ghatak also made Bari Theke Paliye (1958), which looks at a young mischievous boy, who regards his father as a tyrant and runs away from his village to Calcutta only to be wizened by the harsh life in the city and return back.

Perhaps Ghatak’s best work, certainly his most well-known one, is undoubtedly Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), the first film in a trilogy examining the socio-economic implications of partition. In the film, the protagonist Nita (superbly played by Supriya Choudhury) is the sole breadwinner in a refugee family of five. Everyone exploits her and ultimately the strain proves too much as she succumbs to tuberculosis. In an unforgettable moment, as the dying Nita cries out “I want to live…”, the camera pans across the mountains accentuating the indifference and eternity of nature even as the echo reverberates over the shot. Meghe Dhaka Tara reaches out to the audience with its directness, its simplicity, and its unique stylistic use of melodrama but it also goes into far deeper complexities To quote filmmaker and critic Kumar Shahani, “The triangular division, taken from Tantrik abstraction, is the key to the understanding of this complex film. The inverted triangle represents in the Indian tradition, fertility and the femininity principle. The breaking up of society is visualized as a three-way division of womanhood. The three principal women characters embody the traditional aspects of feminine power. The heroine, Nita, has the preserving and nurturing quality; her sister, Gita, is the sensual woman; their mother represents the cruel aspect. The incapacity of Nita to combine and contain all these qualities… is the source of her tragedy. This split is also reflected in Indian society’s inability to combine responsibility with necessary violence to build for itself a real future. The middle-class is also seen in triangular formation, at the unsteady apex of the inverted form.”

Ghatak followed Meghe Dhaka Tara up with Komal Gandhar (1961) concerning two rival touring theatre companies in Bengal and Subarnarekha (1965). This last film of the trilogy is a strangely disturbing film using melodrama and coincidence as a form rather than mechanical reality. To quote Ghatak himself, “I agree that coincidences virtually overflow in Subarnarekha. And yet the logic of the biggest coincidence , the brother arriving at his sister’s house provoked me to orchestrate coincidence per se in the very structuring of the film. It is a tricky but fascinating form verging on the epic. This coincidence is forceful in its logic as the brother going to any woman amounts to his going to somebody else’s sister.”

Ghatak also had a brief stint as Vice-Principal of the Film & Television Institute of India Pune (FTII) in the 1960s, a time he recalled as a happy experience. His presence tremendously influenced filmmakers like Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, John Abraham and Subhash Ghai, then students at the FTII. In fact, Ghai, though working in hardcore Bollywood, mentioned in an interview that whatever few moments of cinema were there in his films, they were entirely due to Ghatak!

Ghatak’s next feature film coming much much later after Subarnarekha, Titash Ekti Nadir Naam (1973), done for a young Bangladesh producer was not something that went off well. The film, on the life and eventual disintegration of a fishing community on the Titash, was completed after many problems at the shooting stage including his collapse due to tuberculosis and in spite of moments of true brilliance, was a commercial failure.

Ghatak made one more film before his death Jukti Takko Aar Gappo (1974) the most autobiographical and allegorical of his films. He himself played the main role of Nilkanta an alcoholic intellectual and the film is remembered for his stunning use of the wide-angle lens to most potent effect. The film also won the National Award for Best Story. Besides feature films, Ghatak also directed several documentaries and wrote various essays on film. He also wrote short stories and scripts for a number of films including Swaralipi (1961), Kumari Mon (1962) and the Uttam Kumar starrer, Rajkanya (1965). He also enjoyed a second stint at the FTII in the mid 1970s influencing a new generation of filmmakers such as diverse as Saeed Akhtar Mirza and David Dhawan, the latter remembering being blown away by Meghe Dhaka Tara.

Unfortunately for Ghatak, awarded the Padma Shri in 1970, his films were largely unsuccessful, many remained unreleased for years and he abandoned almost as many projects as he completed. Ultimately the intensity of his passion, which gave his films their power and emotion, took their toll on him, as did tuberculosis and alcoholism as he passed away on 6th February, 1976. However, he has left behind a limited but immensely rich body of work that no serious scholar of Indian Cinema can ignore.