It is 1856, a year before the Great Indian Mutiny and Lucknow, the capital of the kingdom of Awadh is steeped in sensual stupor. Its ruler, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah (Amjad Khan) is more interested in the pursuit of art and culture than ruling his kingdom while two of his fiefs – Mirza Sajjad Ali (Sanjeev Kumar) and Mir Roshan Ali (Saeed Jaffrey) are obsessed with the game of chess at the expense of their administrative and domestic duties. The British sets its eyes on Awadh and wants to annex it on the pretext of misrule, despite the fact that the kingdom is already under a friendship treaty with the East India Company and provides it with soldiers and money whenever required. The Indian Governor General of that time, Lord Dalhousie entrusts the Resident of Lucknow General Outram (Sir Richard Attenborough) with the unholy job of convincing the Nawab to hand over his kingdom by signing a new treaty. Despite grandiose posturing not to comply with the demands of the Company, Wajid Ali Shah eventually acquiesces and the British army marches into Lucknow while the two landlords continue to play chess at a deserted landscape, indifferent to the historical changes that are occurring under their nose.

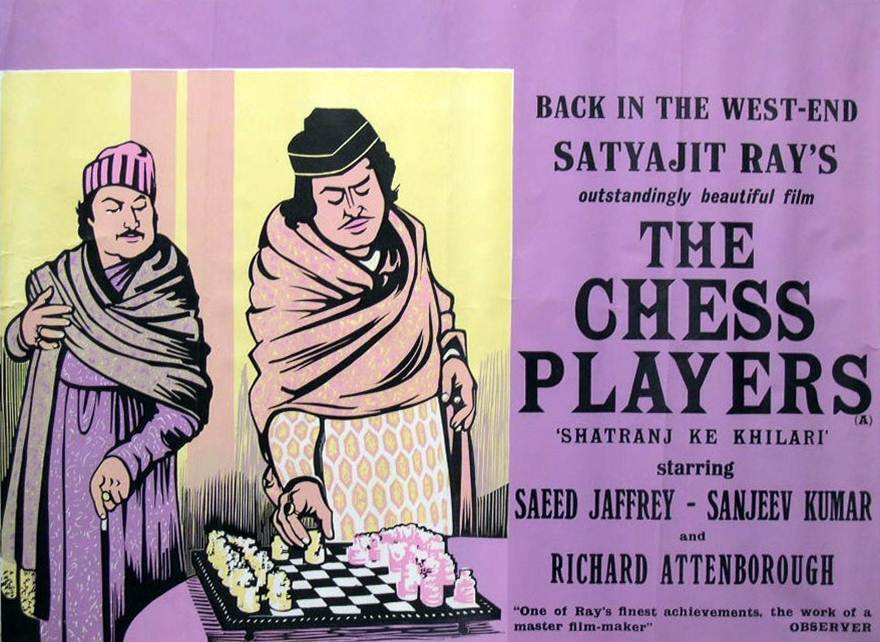

Satyajit Ray encountered the short story by the famous Hindi writer Munshi Premchand in the early 1940s and was immediately drawn towards it because of his interest in “chess, the Raj period, and the city of Lucknow itself.” When he finally adapted it in 1977 into a Hindi film which was his first foray into that language and his most expensive film, he re-hauled the story and widened its scope. The original story had only the two main characters, the jagirdars Mirza Sajjad Ali and Mir Roshan Ali and dealt with their obsession with chess in the vortex of sweeping historical changes. In the film he introduced another strand – Nawab Wajid Ali Shah and the British’s manoeuvres to annex his kingdom. The resultant film is an elaborately balanced and clever allegory. The two strands never meet in the film, but are nevertheless united by a wider historical purpose and context.

Painstakingly researched and extremely well written, this political satire has lent itself to abundant interpretations over the decades because of its rich subtexts and multi layers in which it operates. To begin with, the game of chess from which the film derives its name operates at least at three different levels. First there is the literal chess game being played between the two landlords; then there is the metaphorical chess game which his being played between Wajid Ali Shah and the Lucknow Resident; and thirdly it is reflected in the manner in which the respective wives of the two landlords engage their husbands: Mirza’s wife Khurshid (Shabana Azmi) engages in a variety of tactical moves to regain her husband’s attention; she feigns headache, tries to seduce him and when that fails, steals his chess pieces; while Mir’s wife Nafisa (Farida Jalal) is more proactive; she takes on a lover (Farooq Sheikh).

Ray takes an almost non-partisan view of the political game to the risk of being overly polite. He neither sides with the Nawab nor the British, though there are well-crafted moments when we feel sympathetic towards both the kohl-eyed king and the reluctant General and appreciate their respective stands. Sometimes the director seems to be amused, sometimes meditative. This apolitical stance the film takes further illustrates Ray’s fundamental point: extreme ennui. Ray himself has said that he was “portraying two negative forces, feudalism and colonialism. You had to condemn both Wajid and Dalhousie. This was the challenge. I wanted to make this condemnation interesting by bringing in certain plus points of both the sides. You have to read this film between the lines.”

The film opens in absolute black, as the two chess players sit and play, their vacuum accentuated only by the hookah lying next to them. The game is afoot, and as Amitabh Bachchan’s magnificent voice tells us, this seems a constant state of affairs. The mood and tone are immediately set and we are drawn into the history of the period and the ennui that was Lucknow. The director resorts to some incredibly quirky and simplistic animation to aid his narrative and for a considerable stretch of time it looks like a docu-drama.

The film packs in a lot of information like this, some directly, through voice-over and animation and at other times in an oblique manner that throbs with subtexts. One recalls a scene at the beginning when their game is interrupted by the visit of a dewan (played by David) who informs them of the new rules that the British follow to play the game that had originated in India. He sets about explaining to them the nitty-gritties of the new method which is faster and where the queen has a bigger role to play. But the jagirdars are not impressed; they want to stick to the age-old rules. They also don’t pay heed to his warning that the British are planning to take over Awadh. They laugh it away by saying that the kingdom provides soldiers and taxes to the British; so why would they bother to annex it? This scene does not move the story forward in any way; but what it does is provide a lot of dope on the impending historical makeover, the indifference of the people who should have been privy to this fact and done something to stop it, but who cannot read the writing on the wall. It also serves to underline their pathological obsession with the game, which would prove costly. And of course, the new method of playing chess faster is a direct metaphor for the impatient but crafty maneuvers by which the British are about to take over the kingdom of Awadh without a single shot being fired.

Nawab Wajid Ali Shah comes across as a most colorful regent. He has a ‘harem the size of a regiment’ (400 concubines and 29 muta or pleasure wives to be precise); he composes songs in the middle of a crowded durbar if he ever condescends to summon one; he ties ghoongroos around his ankles and dances thumri and plays rasaleela with his concubines; watches mujras and wallows in the depths of sensual pleasure. But he also prays five times a day and does not drink! Governance is his last priority, but he is sure that his subjects are happy because they sing his compositions in the lanes and interiors of Lucknow! He proudly proclaims that not even the British Queen could match his skill in poetry and popularity. But what he is blissfully unaware of is that the British are not impressed by his patronage of art and culture and hold him directly responsible for the misrule and decadence of Awadh. His prime minister (played by Victor Banerjee) tries to drill into his head the imminent danger of a takeover, but he, like a stuffed toy in regalia declares that he will not give up without a fight. But he does, eventually, when he realizes that he is really incompetent; he hardly has an army who could put up a brave fight and most of the young men have already been enrolled by the Britishers. Wajid Ali cuts a sorry figure in the history of one of the most important epochs in 18th century India; he lets himself be moved like a chess piece on the historical board of colonial India without any resistance.

Sir Richard Attenborough in the role of General Outram enacts some of the most brilliantly written scenes in English along with his subordinate Captain Weston (Tom Alter). Outram is troubled with the illegal means he must follow to take over Awadh despite a treaty of friendship with the kingdom, but he feels bound by his duty to the British Empire. More as an excuse for the justification of the dirty work that he is required to do, he engages in some of the most sparkling and witty lines of dialogues that throw a lot of light on the king’s character and the state of affairs.

There are no heroes or villains in this film. Only tragic-comic figures whose fate is manipulated from London through their representatives in India for the sake of greater profits. It is futile to take potshots at these puppets, both white skinned and brown. One can only laugh at the immense absurdity of the grim historical canvas that has been meticulously built up through minute details that is reflected in the impressive art direction by Ray’s old time companion Bansi Chandragupta and his young associate Ashoke Bose. The period setting is established by lavish sets, elaborate costumes (Shama Zaidi doubles up as costume designer) and well-decorated yet smallish interiors of the two landlords.

The film is peppered with brilliant and witty scenes that depict the two characters Mirza Sajjad Ali and Mir Roshan Ali in their endeavor to play chess against all odds. They come up with the funniest methods and solutions to continue with their obsession. When Mirza’s wife Khurshid (Shabana Azmi) fails to seduce her husband, she steals the chess pieces, assuming that this would bring him back to her amorous arms. Not one to be daunted, the sexually wasted Mirza substitutes the pieces with vegetables and fruits. A hurt and resentful Khurshid walks through the corridor as the camera speedily tracks along with her (reminiscent of Charu’s walk holding the binocular through the grills of the balcony in Charulata (1964)); as she reaches the threshold of the drawing room, she throws the pieces back through the door at her husband and the two players, like kids, bend down on the floor and begin to pick up the pieces. Mirza realizes the gravity of the situation and decides to shift venue to Mir’s house. Mir’s wife Nafisa is almost caught with her lover Akhil when Mir accidentally enters the bedroom and Akhil tries to hide below the bed. In this brilliantly directed humorous scene, Mir is taken in by his wife’s explanations that Akhhil is trying to hide to evade the forced conscription by the Nawab’s forces to fight the British army. A zapped Mir tells his nephew not to worry and orders his wife to give him hot milk and then walks away to rejoin his friend who is waiting to resume the game while the lovers laugh away to glory.

In another outstanding scene before this, the two friends go to a lawyer’s house because they recall that he has a chessboard at his drawing room. They begin to play surreptitiously as the old lawyer lies on his deathbed inside. Out of politeness, they interrupt their game and go to the interior to have a look at the lawyer who immediately has an attack on seeing them and dies. Their game is thwarted, wails fill up the house and the two friends steal out of the house like thieves to look for alternative locations. This is amongst the most comic treatments of a death scene in Indian cinema.

In an earlier scene where Mir is left on his own at the chessboard while Mirza goes off to ‘see what the trouble is’ with his wife, the camera follows Mir as he gets up and goes out into the hallway to see where his friend has got to. The camera then stays still as he retraces his steps, tracks back along with him and in the vertical slice of light caused by a gap between two curtains that separate the hallway and the chess room, we see framed the precise point on the chessboard where Mir’s hand slowly and surreptitiously comes into view as he sneakily moves one of the pieces. A virtuoso piece of camerawork and compositional framing that, like the film as a whole, never fails to enchant.

The show must go on, seems to be their motto, come what may: The game must continue, damn the British army who have already started marching in. Mirza and Mir have taken shelter in a deserted spot to escape recruitment by the Nawab’s army and play their favourite game in peace. Mirza gets irritated by the mosquitoes and his impending defeat at the hands of Mir. To take out his frustrations he casts aspersions on Mir’s wife. Mir takes offence and an argument ensues. Mir draws his gun and accidentally shoots Mirza. Mirza is not hurt but is zapped out of his wits; so is Mir. Thankfully, the two of them realize the gravity of the situation and futility of their argument and Mir comes to terms with his wife’s infidelity. Mir famously admits that how can they defend their kingdom when they cannot take care of their wives? Under the given circumstances, there is nothing more important than another game of chess and the two friends sink their differences and engage in yet another round, but this time following the British method, maybe as a token of the takeover signaled by the marching British army in the long shot.

In the original story by Premchand the two fiefs kill each other. But in the film they are kept alive by the director, perhaps to justify that the two generals were already emasculated even before the British takeover; so it is futile to kill them, though opinions are still divided as to which one was the better ending.

Shatranj Ke Khiladi is a sumptuous audio-visual feast that is still delightful to watch. The songs and the dances (Birju Maharaj as the choreographer) successfully evoke the sights and sounds of a bygone era and we are offered a rare glimpse of nawabi Lucknow that we have heard so much about. All the main actors give remarkable performances. The casting of Amjad Khan as Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was a masterly stroke because the late actor bore a striking resemblance to the original king of Awadh, almost to the point of being uncanny if one looked up representations of Wajid Ali in oil paintings from that period. And one can’t help but smile at the irony that Sanjeev Kumar’s character spends most of his screen time with his arms cloaked into invisibility.

The film went on to win the National Awards for the Best Hindi Feature Film and the Best Colour Photography.

Hindi, Historical Drama, Color