A lower middle-class, newly wedded Muslim couple, Hamid and Salma (Sanjeev Kumar, Rehana Sultan), find affordable accommodation in the city of Bombay in a flat that was previously the dwelling of a courtesan/prostitute, Shamshad Begum (Shakeela Bano Bhopali). Even as Hamid, a honest clerk in a company, and Salma try to live their lives the best they can, the courtesan’s old clients keep landing up and disturbing them, playing havoc with their married life as they take Salma also to be a prostitute. A short but happy break in Salma’s village is but a brief period of bliss before they return to Bombay where events start spiraling out of control. Beset by financial problems, Hamid casts aside his principles and agrees to take a bribe and Salma too performs for one of Shamshad’s clients. However, the young couple pull themselves back just in time and look forward to sharing what they hope would be a better future ahead with Salma being pregnant…

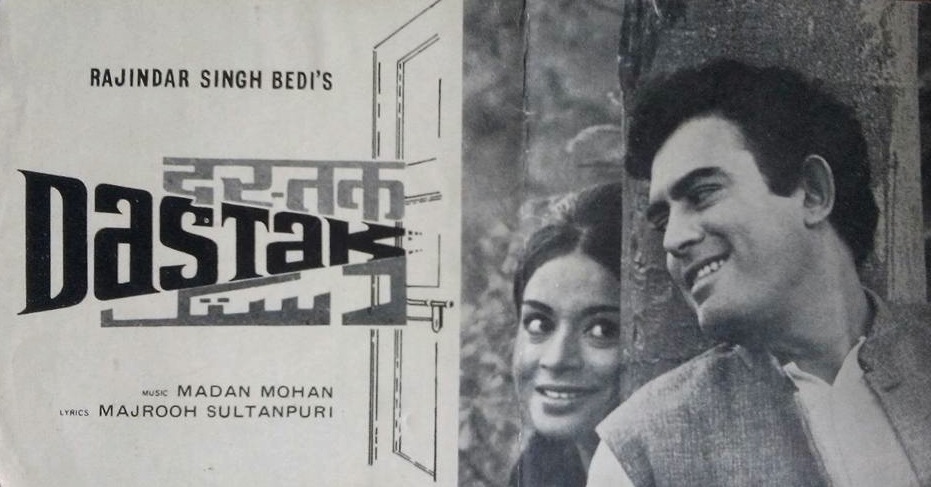

Dastak, directed by Rajinder Singh Bedi and based on his own radio play Naqi-e-Makani from the 1940s, is one of the more important films of India’s middle-of-the-road cinema of the 1970s. Through the efforts of filmmakers like Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Gulzar, Basu Chatterjee in Hindi and KG George in Malayalam, these films offered a more realistic look at life of real people and their issues without totally abandoning the typical tropes of Indian mainstream cinema. In that sense, they satisfied both the masses and the classes through some fine films like Anand (1970), Piya Ka Ghar (1972) and Achanak (1973). So while on one level, Dastak does offer a more natural look at the struggles of the just-married couple, on the other, it also utilizes elements of melodrama, typical metaphors and songs. While no doubt, Madan Mohan’s music in the film is superb, the film, shifting between realism while not totally abandoning mainstream Hindi cinema’s prototype cinematic grammar, does fall at times in no man’s land. Apart from some incredible highs – and there are quite a few – there are enough moments that today appear pedestrian, typical and even dated. That said, Dastak has more than enough going for it and is able to overcome its inconsistencies and largely makes for engaging viewing.

One primary reason for this are the brilliant performances of the lead pair, both of whom would go onto win the National Award for Best Actress and Best Actor, respectively. Rehana Sultan, an acting student from the then Film Institute of India, today FTII, makes an absolutely stunning debut. No doubt, the film favors Salma and stays with her more than Hamid, but she is more than up to it. Sultan captures every shade of her character perfectly starting from the excitement of the beginning a new journey in the city to finally a stoic acceptance of reality of her life. It is a refreshing, different and real performance, unlike those seen in mainstream Hindi cinema, and one of the earliest from the emerging Film Institute graduates to make a mark, thus setting the path for future actresses like Jaya Bhaduri and Shabana Azmi. One wishes her developing graph was more plausible though even though the film does its best to get into her mind and make us invest (heavily) in her. One of the most telling moments in her performance is when she tenses up hearing footsteps climbing up the stairs outside their flat terrified that it would be one of Shamshad’s clients only to be relieved as the sound of the footsteps recede and move on past their flat. Sanjeev Kumar, too, is spot on as the harried husband, wanting to live a life of honesty and dignity but having his own battles to fight, looking after Salma and her impoverished family in the village, while trying to buy his own little flat in Bombay.

With the film largely safe on the shoulders of these two, the supporting cast too do their part. Manmohan Krishna is his usual efficient self as the kindly old man of the locality, Anwar Hussain is perfect as the slimy paanwala as is Shakeela Bano Bhopali as the courtesan/madam. Anju Mahendroo manages to make a strong enough impact in a frustratingly underwritten track of Maria, a colleague of Hamid’s at work, who nutures a soft corner for him.

As mentioned earlier, there is much the film gets right especially in its visual treatment. Bedi, making his directorial debut in his 50s, effectively contrasts the claustrophobia and complexities in the big city with the openness and simplicity of Salma’s village. Salma’s life in the city is almost always indoors, the walls of her flat surrounding her or we (much too obviously) see her often behind the window grills of the house or besides her prized possession of a caged mynah, thus highlighting her ‘house arrest’. This is against the vast tracts of rural landscape, where she and Hamid run about in sheer bliss, signifying the liberty she enjoys in her own village. The film sensitively looks at the harrowing effects the big city has on outsiders who come there to make a living and how easily they would be eaten up if he or she are not careful. Even when the husband and wife spend the night out on Bombay’s streets to avoid Shamshad’s clients from disturbing them, they find themselves questioned by a cop about their credentials and there is even an attack on Salma. It is as if everywhere they go, they cannot escape her being objectified. Which perhaps Bedi could be a little guilty of as well, even if he meant otherwise, as we see in the sequence where Sultan takes of her clothes and lies naked under the sheet in the Mai Re song. I feel this because the ending with her being pregnant is looked at with hope that she is now going to be a complete woman beyond objectification after all she has gone through.

Dastak handles its adult themes, particularly the sexual tension of the newly-married couple, pretty well as they struggle to get some quality time alone only to culminate in a horrific marital rape as Hamid’s frustrations build up. Sadly, the film abandons this track as the husband and wife are perfectly normal in the very next scene. One is confused with Bedi’s treatment here as one is not sure whether he felt it best not to go too forward with this daring angle or whether to him, such acts were typical and no big deal in India’s terribly patriarchal society that is largely accepted by both genders. As Dastak shows, it’s always the woman who suffers the brunt much more than the man.

The other big, big highlight of the film is Madan Mohan’s exquisite National Award winning music with some deep and truly thought-provoking lyrics by Majrooh Sultanpuri. Each of the songs is situational and rendered perfectly by Lata Mangeshkar and Mohammed Rafi. Lata, in particular, is in absolutely sublime form, particularly in the Hum Hain Mata-e-Koocha Bazar Ki Tarah lament, easily one of the best songs of her career. Special mention also has to make of Kamal Bose’s evocative black & white cinematography and Sudhendu Roy’s art direction. The editing by Hrishikesh Muherjee appears surprisingly choppy giving the film an uneven narrative flow but then an editor is bound by the filmed material. I suspect some of the inconsistencies in the rhythm and pacing of the film are more due to Bedi’s filming of them rather than any shortcomings on Mukherjee’s part.

All in all, for all its inconsistencies, the highs easily outweigh the low, thereby making Dastak one of the more relevant films of its time. Sadly for Rehana Sultan though, with Chetna (1970) coming soon after, where she perfectly enacted another bold character of a prostitute, her career failed to take off. Mainstream filmmakers failed to see her in more’ typical’ roles and/or were simply clueless on how to utilize her great talents as an actress. Dastak reminds us starkly just what a tragedy that was.

Hindi, Urdu, Drama, Black & White