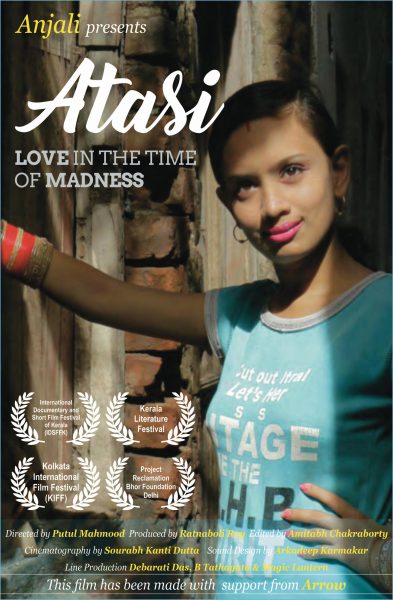

In an on-camera interview in 2015, filmmaker Putul Mahmood had said that it all depends on what a film is choosing to look at. For instance, one choice could be to look at the victimhood of a person but not explore where or how he or she is empowered. Thankfully, she chooses the lesser taken, latter path in her documentary, Atasi (2018). What unfolds, thereafter, is a riveting, exhilarating, highly disturbing but above all, humane film that celebrates its protagonist, Atasi. It is a film that Putul labels, ‘love in the time of madness’, also the film’s tagline.

Atasi is commissioned and produced by Ratnaboli Ray, the the founder of Anjali Mental Health Rights Organisation. There is a back story from where the film takes off and which we mostly hear through Atasi. When her father died, her relationship with her mother and brother deteriorated and she was forcefully dragged out of her home, beaten up brutally by the police and taken to the Calcutta Pavlov hospital. This move, according to her, was engineered by her mother, brother and late grandmother, which makes it all the more shocking. After spending time in appalling conditions at the hospital, she returned to a none too happy home. But life has its odd way of sorting things out. Atasi found solace in an online friend, Deep Harry, a Punjabi mechanic then based in Saudi Arabia, which resulted in love and marriage. He was just the supportive catalyst she needed, who made her feel wanted and valued. His love helped her to not only find much strength within herself but also empowered her to deal with her life and family. Following her marriage to Sandesh (his real name), Atasi relocated to Punjab. Putul shot the film when the couple came down for a trip to Kolkata.

In a film that has mental illness as a backdrop and since we see Atasi only post ‘recovery’ and speak so eloquently and clearly about her ordeal, it is difficult for us to imagine that she could have been so insane as to have needed confinement in a mental hospital. The closest she comes to admitting she had issues is when she says that she was not sure of what was going on in her mind and that something was not right. As she takes her horrific story forward, we connect with her, empathize with her and most importantly, we tend to believe her side of the story. But even as we applaud her for dramatically turning her life around, post the film, a stray thought does niggle at the back of the mind that lies unexplored. Perhaps an external insight from her psychiatrist or the hospital about her mental state at the time of her admission there and her subsequent stay there for two years might have given us a truer and more fuller picture of Atasi and her family’s story. The family, too, is looked upon as an aside and as not so nice. So, as it is now, the full narrative focus in the film is on Atasi and her return to ‘normalcy’ and reclaiming her life within her family. This is rich in its own way, I suppose, and while we have to respect Putul’s choice to strictly stick with her protagonist and see the film from Atasi’s POV, we also have to guard ourselves from becoming unfairly judgemental towards Atasi’s poverty-stricken family. Surely they have their stories too in which they are the heroes.

What works well in the film that Putul has filmed Atasi’s story fluidly and instinctively depending on the situation in front of her without a rigidly fixed style but always keeping Atasi in focus. Of course, it helps that Atasi has a fantastic rapport with the camera and owns the film. So we have a dramatic follow shot – front and back – through the narrowest of lanes through the locality where Atasi’s family’s old dilapidated house is situated, moving along with Atasi as she tells us how she was dragged through those very lanes and taken away to the hospital; as against this her outings with her husband, Sandesh, in Kolkata are very much fairytale-like or plain ‘filmi’ as they take a carriage ride at night or take selfies by the Howrah river. There is a lovely sequence where they take a boat ride on the river and Atasi revels in the beauty and serenity all around her. It reflects on how life with her husband is – happy, calm and tension free. She loves and is loved in return. There is inadvertently a little moment here when in their conservation, her husband tells her that staying with him she will have a good life. But staying with her mother and brother, she will drown. This, when they are on the boat!

Two sequences, in particular, resonate tellingly about Atasi’s life today and more importantly, how she sees it. And both are with Sandesh. One is when she visits the gurudwara in Kolkata. She tells us she goes here with her husband because it reminds her of Punjab. We realize she has taken to her new home and is now probably a happier person outside Kolkata. As an aside, her spoken Punjabi isn’t too bad either! The other part, which tells us clearly that Atasi has exorcised the inner demons of her past and is not afraid or disturbed to revisit the ‘scene of the crime’ as it were is when she goes with him to Pavlov hospital to meet and catch up with the inmates. This literally connects Atasi’s past to her present.

Sometimes, the documentary form, which is supposed to be more ‘truthful’ than fiction, creates a different set of problems for the viewer. Looking at Atasi’s dysfunctional family so directly upfront and as starkly as Putul does is disconcerting at times. One would not give much thought to watching a maladjusted family going hammer and tongs at each other in a fiction film. But here, there are actually enough times when one wonders whether a certain ethic of privacy is being breached or not. Sure, you could argue that those being filmed know the camera is on them and they’ve not asked Putul to stop filming them. But seeing the argument between an assertive and resurgent Atasi and her brother with occasional participation of her mother – and it goes on for quite sometime – is vexing and even unnerving at times. Putul’s intention here is to obviously make sure you face the uncomfortable square on and see everything as it is without any sugar coating whatsoever. Admittedly, this helps you understand exactly where Atasi stands today with her family. And like most families, it is a far more complex relationship they share among themselves. If there is hostility at one end, there are enough times you feel the family is as close and bonded as ‘normal’ families are. We see that for all the animosity between them, each side understands that it cannot really do without the other. We again see this at the end when the mother is desolate and at one point even breaks down at the prospect of Atasi going back to her married life in Punjab. And as the train leaves taking Atasi back to her fairytale life, the end titles rolling over her kitschy marriage DVD give her story the perfect ending!

Atasi has been screened at various festivals including the 2018 editions of the Kolkata International Film Festival (KIFF) and the International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala (IDSFFK). It also went on to win the Silver Conch for the Best Documentary Film under 60 minutes (it is about 52 minutes long) at the 2020 edition of the Mumbai International Film Festival for Documentary, Short and Animation Films (MIFF).

Documentary, English, Punjabi, Bengali, Color