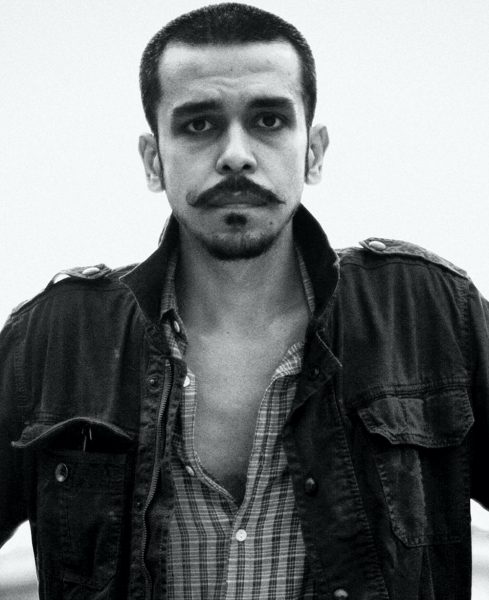

With an impressively artistic body of various short films and three feature films in his oeuvre, Devashish Makhija is a filmmaker whose idiosyncratic style and directorial flair have constantly pushed the traditional boundaries of storytelling. His recent outings, the short films Cheepatakadumpa (2021) and Cycle (2021) are a further extension of his efforts in exploring concepts and themes that are compelled to initiate discourse. In Cheepatakadumpa, two women, Teja and Santo, teach their friend Tamanna how to bloom and follow her hilarious journey of self-discovery. Cycle, on the other hand, is an unflinching account of how violence perpetrated upon a downtrodden tribal community by the individuals in power ends with brutal repercussion. Shot on a mobile phone camera, by three different actors, there is no escapism in the claustrophobic treatment of the film.

Cheepatakadumpa recently won the Gender Sensitivity Award at the latest edition of the Dharamshala International Film Festival (DIFF) last month while Cycle is to be screened on December 12 and 13, 2021 in the Competition Section for Short Fiction at the forthcoming International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala (IDSFFK).

I recently spoke with the filmmaker to discuss some of the artistic and critical choices that went behind in the making of these two shorts.

You have said Cheepatakadumpa was shaped out of weeks of rehearsals and improvisation. However, such creative exercises can be endless processes. So at what point, as a filmmaker, did you decide to just go ahead and shoot the film?

Devashish Makhija: When it is a short film you’re producing with your own money, an endpoint to the process no matter how meandering and open-ended is predefined to a certain extent. Otherwise, I cannot pull off a film of any artistic merit and originality within very frighteningly limited resources, which was the case with this film. So, I reached out to the actors of the film saying that these are the themes that I want to explore, this is the kind of intent I have with the process that I would like to undertake to ‘find’ the film. And so I would need to spend time with them to play out these ideas so that I could find a story and solidify the characters, which I would write through the process of self-discovery with them. I also told them that we would begin the rehearsals in September 2019 and around January 2020, we would shoot the film.

While the process we undertook was freewheeling, there was a constant watchful eye that a filmmaker needs to keep, constantly trying to push back things on track when you feel that they are sort of losing focus or meandering. To be honest, I did not have an ending to the story or any sort of clear culmination in mind when we began. But I did know what I wanted this film to say. Where and how the story of the film would end up was something that I did not know. When we did those endless weeks of rehearsals, improvisations, trying out various things, swapping characters and taking them to newer places, the boundaries that we were working within were being set and getting constantly solidified. I did not want the characters to stray too far because at some point, I had to end this process and sit down to write what we had arrived at and thereafter, shoot the film. So, could I define specifically at what point I stopped this process of discovery and decided to get on the field and manifest what we have found? No. It is impossible to pinpoint that exact moment. But when you have preset dates or a specific schedule in mind, the subconscious takes over. It slowly works its way into the driver’s seat and starts steering one towards some sort of endpoint.

Cheepatakadumpa has a lightened mood and a humorous narrative while Cycle is dark and cruel in tone. How do you maintain an even balance in your cinematic voice while making films with such contrasting themes?

Devashish Makhija: This is the only time I’ve tried to simultaneously create two such works that are so contrasting in tone, theme, genre, mood and intent. Actually, I was initially just planning to make Cycle. We were going to another city with the spirit and energy of a theatre troupe. It was going to be a collective, community experience. I had pulled in so many scattered resources to make this film happen that I wondered why I was going to such great lengths to return with just one short film?! Why not try and crack another while we’re at it. And if this film is going to be taking us into the heart of all kinds of darkness, why not make another that may be the Yin to this Yang? So that this collective of people could have an emotional smorgasbord of experiences while making these two films together. That’s how Cheepatakadumpa was born – to help us all not tip over the edge of sorrow and rage while making Cycle. Perhaps the balance you speak of came from there? That the second film was conceived to iron out the creases left by the first?

What sort of research went behind in the making of Cycle to bring authenticity to the narrative?

Devashish Makhija: If you ask me, I think ‘research’ is a much misunderstood word. When a storyteller has lived with material for so many years within him/herself, that itself perhaps counts as ‘research’? I have been reading up on, debating, experiencing, witnessing, journeying and engaging with the Adivasi struggle for over a decade. I have drawn out countless stories from the situation over the years – my first feature Oonga (2013), which is now out as a novel, multiple short stories in my anthology Forgetting, and even a forthcoming feature that I’m currently setting up starring Manoj Bajpayee. Cycle emerged from all that I have internalised and understood and felt for and been moved by over these years. As such when we got down to making it, I was all the research this film needed. The team and I had endless conversations. I showed them endless images, both static and moving, that I had curated over the years. Perhaps that brought in some authenticity. Does a piece of fiction ever achieve complete authenticity? Does it seek to? Does it need to? I don’t know. And I’m not sure.

Could you share your process of preparing the actors before shooting the violent scenes in Cycle with such gritty realism?

Devashish Makhija: Cycle had ten days of workshops and exercises (conducted by Bhumika Dube), rehearsals, discussions, playing out of the scenes in safe spaces and then multiple times at the actual locations before we even attempted to shoot it. Primarily because I was taking the actors into hitherto unfamiliar and unsettling places. The value of discussion – talking about the film, the process, the politics, the philosophies of the characters’ as well as that of the actors’ and the filmmaker’s – is vastly undervalued in our film industries here in India. A lot of the trust that builds between the actors and director emerges from simply taking the time to know and value and cherish one another before we undertake those difficult and personality-altering journeys together into the world of the film itself. When the film has extreme emotions – violence being one – it is that much more imperative that trust be built between the people making the film together. All the ‘realism’ you find in this film is arrived at eventually via this difficult and arduous process of mutual discovery.

You have co-edited both the short films with Ronak Singh. Did it help you to enhance your vision as a director?

Devashish Makhija: Truth be told, I tried to get other editors on board for Cheepatakadumpa. But on a short film so crunched on resources, money and time, no editor was able to give me the time, energy and investment I needed to help me discover the film. All else failing, I took the plunge with my First AD Ronak, who is also a fine technician and a post-production whiz. Although it felt like we were up against incredible odds at each and every step on these films, in hindsight, the truth is that it is these very odds that also shape the film and our own growth as artists through the infuriating and excruciating process of making the film.

Cycle on the other hand is just three long uninterrupted shots. The film has only two evident cuts. But it has dozens of invisible cuts that are invisible only so that the shots appear uninterrupted. The editing process of such a film is an awkward one to bring a professional editor onto. So Ronak and I were editing it ourselves in our minds, discussing the cut points and working towards the final edit even while we were prepping, workshopping and shooting the film. It was a most fluid exploratory edit process.

Cycle will be screened at the prestigious IDSFFK this month. How important is this film festival to you and how do you expect the viewers to react to the film?

Devashish Makhija: Almost all my films have been screened in Kerala. El’ayichi (2015), Agli Baar (2015) and Taandav (2016) were shown at IDSFFK while Oonga, Ajji (2017) and Bhonsle (2018) have been screened at the International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK). And now Cycle. When we made this short, I was sceptical of festivals programming it, for obvious reasons. And I was proven right. Most festivals that have even shown my earlier films in the past rejected/ignored/sidestepped Cycle for different reasons. But somehow I was always cocksure that IDSFFK would select it. There is a spirit for the arts in this festival that is unmatched in India. The audiences transcend all kinds of class barriers. The engagement is both deeply intellectual and emotional at once. However, I have no expectations of viewers ever as a rule. But I almost feel certain that Cycle will be received warmly by the viewers here. It is also the first time in a very long time that the team and I will engage with audiences in person, inside a theatre! I look forward to that most. Especially for a film such as this one, that seeks to start difficult face-to-face conversations.

Lastly, as a filmmaker does making short films provide you with much more creative liberty as an artist?

Devashish Makhija: Most definitely, yes. I’ve said this innumerable times in the past. It is the reason I emptied out a lifetime of savings to make these two short films on my own – freedom. I returned from the shoot of these two films without enough money to even cover my rent for the next month. But it means everything to me to be able to explore and discover my film. Paul Thomas Anderson said once that the biggest uphill task for a filmmaker is to fight for the right to discover his/her film. In feature films, I have limitations of all kinds because someone else’s money is at stake. Both Cycle and Cheepatakadumpa needed me to follow a most unpredictable and frightening process of experimenting and exploring endlessly before we ‘arrived’ at the eventual films. Almost no producer/financier on a feature film may allow that – not in this country at least. So I decided to empower myself. Sumeet Kamath, Sreeram Ramanathan, Abhinav Singh and Pria Mundra didn’t just join me in funding the film, but in allowing me to spread my wings as far as I wanted to. I am eternally grateful to them for this.

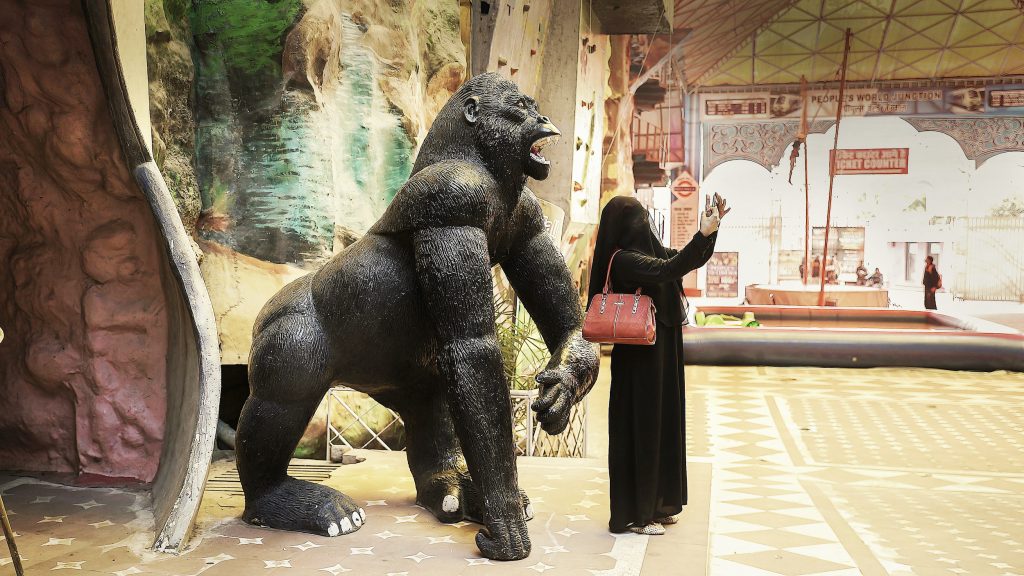

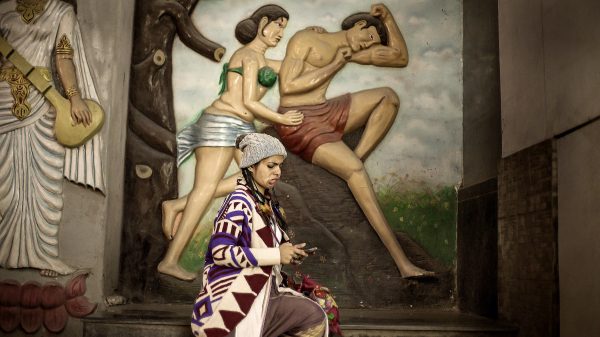

Header picture – Still from Cheepatakadumpa.

All photographs courtesy Makhijafilm.