William Shakespeare’s representation on Indian film has mainly focussed on the Pan-Indian identity of his works on celluloid. Not many academics, Shakespeare and film study scholars have ventured to explore the rudiments of Shakespeare’s representation in regional Indian films in general and Bengali cinema in particular. In the wake of Zulfiqar’s release, one of the biggest multi-starrers in Bengali cinema, it would be interesting to discover how the Bard has been a favourite of Bengali filmmakers for some time now but has reached its peak in the recent past.

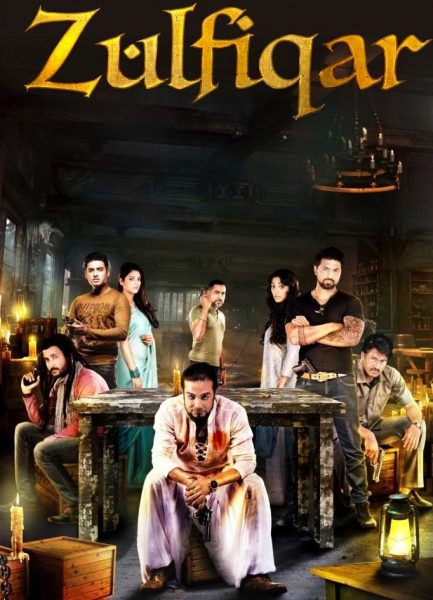

Zulfiqar (2016), directed by hot-shot director Srijit Mukherjee, is a kedgeree concocted out of two famous Shakespeare plays – Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra. Yet, it is named after the 2000 AD-Kolkata mafia version of Julius Caesar, namely Zulfiqar portrayed with an arrogant swagger and heavily accented Bengali by none other than the numero uno Prosenjit. Where does that leave poor Antony and Cleopatra? Antony is split into two characters portrayed by two different actors, Parambrato, who plays Antony, and Dev who plays Marcus. With ingenuity but without logic, Mukherjee turns Antony into a Christian who wears the cross as if to make a point and can converse fluently in Bengali, Hindi and English. He is also the proxy voice of Marcus who is mute and uses sign language translated all the time by Antony. Cleopatra, portrayed by Nusrat Jehan, is beautiful to look at and has an attractive screen presence but lacks the sexual chemistry that one can read clearly in the Bard’s original work and even in the poor but beautiful actress Elizabeth Taylor who’s packaging for Antony and Cleopatra (1963) became more important than the main story. Basir Khan (Brutus), portrayed by Koushik Sen who has performed Shakespeare’s plays in his stage career umpteen times, has been given a hoarse, modulated voice that is a misfit because his popular screen persona includes his original voice and would have served the film better. Mukherjee has not only deconstructed the two plays but has also reconstructed the two narratives linked only through some characters by placing them in the new realm of the gangster underworld with its violence, passion and feudal conflicts of loyalty that has already served several Shakespeare film adaptations in the past. These include The Bad Sleep Well (Kurosawa’s Hamlet), the Macbeth adaptations Joe Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet spin-offs and many more.

The first known Shakespeare reference to Shakespeare in Bengali cinema I can recall is the Suchitra Sen-Uttam Kumar starrer Saptapadi (1961) directed by Ajoy Kar. There is a dramatized recreation of the last scene from William Shakespeare’s Othello staged by the students of the medical college. Krishnendu portrayed by Uttam Kumar, played Othello while Suchitra Sen was cast as Desdemona. The voices of Othello and Desdemona were dubbed by Utpal Dutt and Jennifer Kapoor. This has become as classic as the film itself in a film in which Shakespeare is neither the underlying of the text nor even the source of the plot. It is a cinematic strategy created by the director to establish the chemistry between the hero and the heroine who constantly fight with each other on issues of class, status and presumably, race. An important point to be noted is that neither Uttam Kumar nor Suchitra Sen had any ego hassled about their voices being dubbed by other theatre actors because they knew that these voices would do greater justice to the scene than they would or could.

Bhranti Bilash (1963) was a film based on a play by Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, which was a Bengali adaptation of Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors. The film was directed by Manu Sen with the screenplay and dialogue penned by noted playwright Bidhayak Bhattacharya. Though the original play was set in an unspecified, but distant past, the film relocates the story to modern day India. The film tells the story of a Bengali merchant from Kolkata and his servant who visit a small town for a business appointment, but, whilst there, are mistaken for a pair of locals, identical in looks and behaviour and status, leading to much confusion. In 1968, the film was remade as a Bollywood musical named Do Dooni Char and remade again in 1982 as Angoor directed by Gulzar. Since Uttam Kumar and Bhanu Bandopadhyay played the two masters and their respective servants, the film turned into a rollicking comedy punched with the added comic timing of Sabitri Chatterjee who played the wife of one of the twins. The film was an Uttam Kumar production. Interestingly, the film does not refer to Shakespeare and only mentions Vidyasagar’s novel as its source.

A lesser discussed film based on a Bengali adaptation of Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew was Srimati Bhayankari. In a conference on Shakespeare in Indian Cinema organized by the BFI in celebration of the Bard’s 450th anniversary, Paramita Chakravarti drew attention to the cinematic adaptation of the play in 2001. Srimati Bhayankari (Mistress Terror), the play, remains one of the longest running theatrical productions of Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew on the Bangla commercial stage in the late 70’s. It was made into a popular film in 2001, directed by Anjan Bannerjee. Translated and published in 1976, the performance of the play started 1in 978 under the direction of actor Robi Ghosh. It ran to packed houses in Bijon Theatre for 1000 nights. Says Chakravarti, “Though translator Goutam Ray acknowledged his Shakespearean source in the first printed version of the play, subsequent editions, performances and the film discarded this debt. One of the reasons for the appeal of the play was undoubtedly its folk tale like theme of punishing the unruly woman.” Chakravarti goes on to elaborate, “The 2001 film version intensifies the transformation of the play into a bourgeois melodrama. While the first half of the film follows both Taming and Srimati Bhayankari closely, the second half regresses into domestic drama complete with a confrontation, misunderstandings and bitter conjugal quarrels followed by attempted suicides and last minute reconciliation,” writes Chakravarti. Srimati Bhayankari, according to Chakravarti, represents an instance of how, from being revered as an icon of Bengali modernity and high culture, Shakespeare has become the currency of commercial mass culture. This transformation certainly calls for a different kind of theorization.

Celebrating Shakespeare’s tragic heroes on the one hand and tackling with the persistent conflict between chance and reason is a daunting task. Ranjan Ghosh,who makes his debut with Hrid Majharey (2014) presents a story of intrigue rooted in love and its loss. The story explores these areas mainly from the point of view of its protagonist Abhijit Chatterjee (Abir Chatterjee). Abhijit teaches Mathematics at a noted college and is popular among his students. A chance encounter with a lady soothsayer in a city restaurant triggers a catharsis in his mindset. She makes dark and ominous comments. Inspired by Othello and incorporating elements from Macbeth and Julius Caesar, this was the first film in Bengali based on the works of William Shakespeare to have been internationally considered one of the top five World Adaptations of Othello. Priyanjali Sen (Shakespeare and Contemporary Bengali Cinema: Form, Intertextuality and Mise-en-scene in Hrid Majharey (2014) and Arshinagar, 2015) writes: “Hrid Majharey, was the first to have been publicized as a tribute to Shakespeare for his 450th birth anniversary, beginning with an image of the bard before the opening credits, and incorporating stylistic elements, themes and narrative devices that make it both self-reflexive and in keeping with Shakespearean traditions. Ghosh’s cinematic treatment of Hrid Majharey through intertextual references and mise-en-scene, is refreshing and effective precisely because it is able to circumvent the colonial implications and gravitas of Bengal’s literary/cultural heritage – frameworks that are usually employed in a discussion of Shakespeare in Bengal – modifying and playing with Shakespeare’s characters/styles in order to make his own statement about what Shakespeare means to a contemporary audience.” In an interview to this writer, Ghosh said, “Hrid Majharey has characters inspired by Othello, Desdemona and Cassius from Othello, the Witch from Macbeth, and the Soothsayer from Julius Caesar. Yet, the film is not an adaptation of any of his plays, but has simply drawn on a few characters from them. For someone who has studied Shakespeare, these references will be easily accessible. For others who aren’t familiar with Shakespeare, they’ll see a new kind of a love story!”

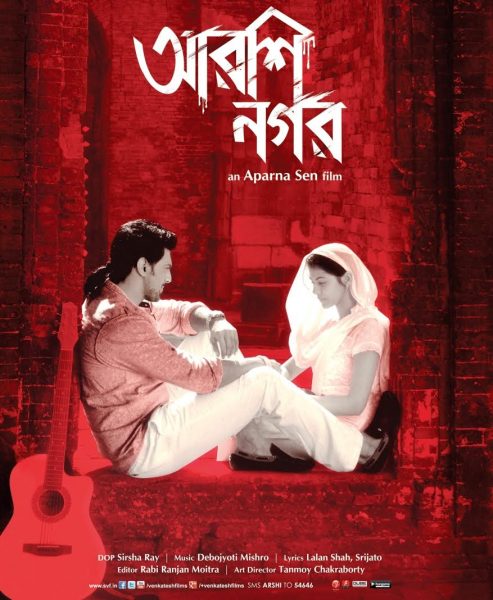

“A Musical Romance based on William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet” was the tagline on every poster of Aparna Sen’s Arshinagar (Mirrorland). Contrary to this tagline, Arshinagar turned out to be the most sharply edged, incisive political comment by the director in her first ever no-holds-barred mainstream entertainment film for over 35 years. The sharpness, one must concede is somewhat blunted by the frothy romance of the con temporized Bengali avatars of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. It is the music, the songs and the lyrics that define the political content of the script, authored by Sen herself. Add to this the imaginatively created rhyming dialogue that spikes the entertainment value and gives the film an added dimension. According to Priyanjali Sen, “Arshinagar, based on Romeo and Juliet is highly informed by the musical genre and aesthetics of West Side Story. Bengali literature and theatre have had a long tryst with Shakespeare, from direct Bengali translations of his plays to the development of literary techniques and characters inspired by his works; and from faithful adaptations to appropriations and distorted re-workings on the stage. In comparison, Bengali cinema has been fairly reticent in its engagement with Shakespeare, other than a handful of films such as Saptapadi” The essence of the film is spelt out in its title – Arshinagar – the mirrorland that is a microcosm representing any pocket on the fringes of an Indian city or town today centred in a slum.

Noted musician, singer and filmmaker Anjan Dutt did not like Vishaal Bhardwaj’s Hindi adaptation of Hamlet, Haider, at all. He rubbished it in a scathing article in The Telegraph (October 15, 2015) titled Where is the Tragedy of Hamlet, stating: “The same man who became very important in Indian cinema to me with Maqbool (Macbeth) and his ‘not that bad adaptation’ of Othello, Omkara, killed my huge expectations with his Haider. Everyone is all out to praise the stunning visuals of Kashmir, the darkness of its politics, deprivation, the greyness of the bridge over Jhelum, etc… No one seems to be bothered about Mr Shakespeare in all this. The sheer irony is that Vishal Bhardwaj had it all. He chose Kashmir of the ’95 with its armed insurrection and human rights violation as a backdrop, which is a fabulous parallel to the rotten Denmark”. Dutt, as his personal reaction to Haider, presented his personal celluloid take on Hamlet, called it Hemanta, timed it forward to fit into the present, adapted it into the Bengali ambience and characterised the main people concerned without steering much away from the Shakespeare original. Hemanta built the story on the background of the Bengali film industry. Parambrato Chatterjee played the title role of Hemanta and though he did as good a job of it as he could, the film per se left one a bit disturbed and confused and puzzled and made one wonder whether the Shakespeare reference was at all necessary for a film that stands well on its own.

Are these Bengali filmmakers rewriting the Bard within contemporary circumstances? Or, are they aspiring that these adaptations and relocations in terms of time and space in the form and content of the film language will function as vehicles for universal truths not necessarily divorced from the time and culture that created them in the first place? Films adapted or relocated or inspired by the works of Shakespeare can, in a larger sense, encompass a broader reference that extends even to “films with an entirely different representational economy and marketing strategy and the best examples are, beyond Indian shores, the animated Shakespeares that reformulate radically truncated texts into images no longer tied to their origin in an actor’s body and its representation of the real.” (Introduction to Shakespeare – The Movie – Popularizing the plays on film, TV and video, edited by Lynda E. Boose and Richard Burt, Routledge, London and N.Y. 1997).

Within West Bengal, the best example of this is in Zulfiqar, where the massive pre-release hype overload, executed and performed live through functions with star appearances and music launches held at shopping malls, open spaces, NGO promotions, music releases alongside media hype on television, the press, the internet and radio have not only undercut the possible negative reviews of the film after its release but has also ensured guaranteed footfalls in the theatres wherever the film has been released.

Franco Zeffirelli, who made three Shakespeare adaptations on film namely The Taming of the Shrew (1966), Romeo and Juliet (1968) and Hamlet (1990), presents the ideal recreation of Shakespeare on film when he says: “I have always felt sure I could break the myth that Shakespeare on stage and screen is only an exercise for the intellectual. I want his plays to be enjoyed by ordinary people.”

Thank you for an excellent article and especially for a fantastic website! It is a great service to Indian cinema.

A small addition — ‘Shakespeare in Indian Cinema’ is actually Dr Chakravarti’s new book — the conference she spoke at was ‘Indian Shakespeares on Screen’, organised by four young lady researchers: Thea Buckley, Koel Chatterjee, Dr Varsha Panjwani and Dr Preti Taneja. May I invite interested readers to visit our website: http://www.indianshakespearesonscreen.com/about