45-year-old Arindam Saha Sardar is a self-taught archivist and restoration artist. He makes biographical documentaries, curates exhibitions of rare artifacts, song booklets of old Bengali films, photographs, lobby cardss, old still and movie cameras, and just about everything he finds of archival interest. Today, his Jibansmriti Archive is known to be the only such archive dedicated to cultural artifacts from literature, through music, theatre, films and now venturing into handicrafts with the archive’s new collection of dolls crafted by the village craftsmen and craftswomen in Bengal.

Tracing the history of te archive, Sardar first founded Bengal Studio in Hind Motor, a Kolkata suburb in a rented garage in 2008. In 2010, the family relocated to Uttarpara and Bengal Studio, a not-for-profit organization, registered in 2015, now has a permanent venue on the ground floor of his residence, renamed Jibansmriti Archive. The Archive now has in its possession, the following collections:

- 22000 rare books and journals

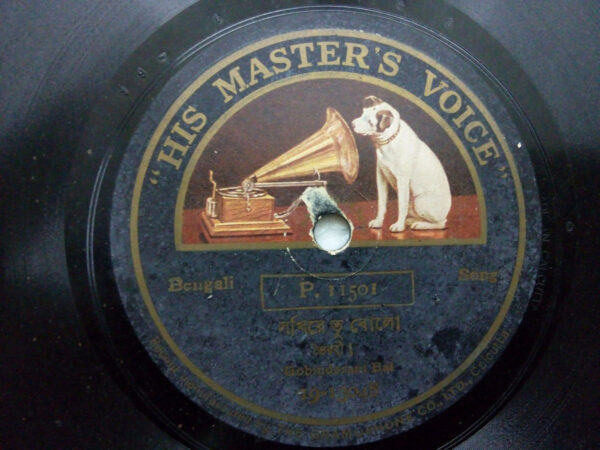

- 5000 music records (78 rpm, LPs and SPs)

- 1000 old letters.

- 2000 film stills,

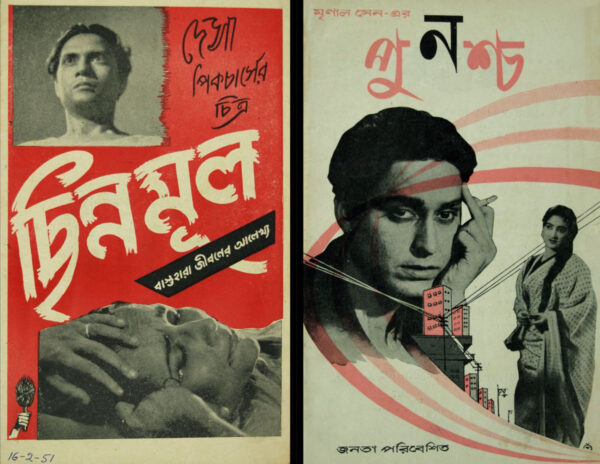

- 2000 film posters,

- 11000 film booklets,

- 400 audio and audiovisual interviews,

- 300 dolls,

- 150 manuscripts

- 100 original drawings and paintings.

There is an entire room dedicated to Mrinal Sen filled with old cameras and other film paraphernalia gifted by Mrinal Sen’s son Kunal Sen. Another section is dedicted to Ritwik Ghatak. Soumendu Roy gifted Arindam with a collection of his old cine-cameras and one priceless notebook which he had preserved when he worked with Satyajit Ray.

Believing the material must be shared with the public, Sardar organizes or is part of regular exhibitions and screenings. of great filmmakers like Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Tapan Sinha and many others. Add to this a long list of theatre artists, cinema and theatre technicians, music directors, singers, instrumentalists – the list goes on.

In 2011, Uttarpara Bengal Studio held an exhibition on music, an offshoot of Arindam’s research on 78 rpm records spanning 1902 and 1971. Some of these songs were played on a recorder while the walls displayed portraits of music directors and vocalists of the time. In 2008, I began to interview people in the recording industry – music directors, singers, lyricists, music arrangers, recordists and even the head of Megaphone Company on camera wanting to make a documentary. Private songs, film songs and all modern Bengali songs fell within this area. It was a great learning experience,” he says.“Recording companies stopped recording on 78 rpm from 1970 but a few offshoots came out in 1971.” Another earlier exhibition was on select works of Nandalal Bose.

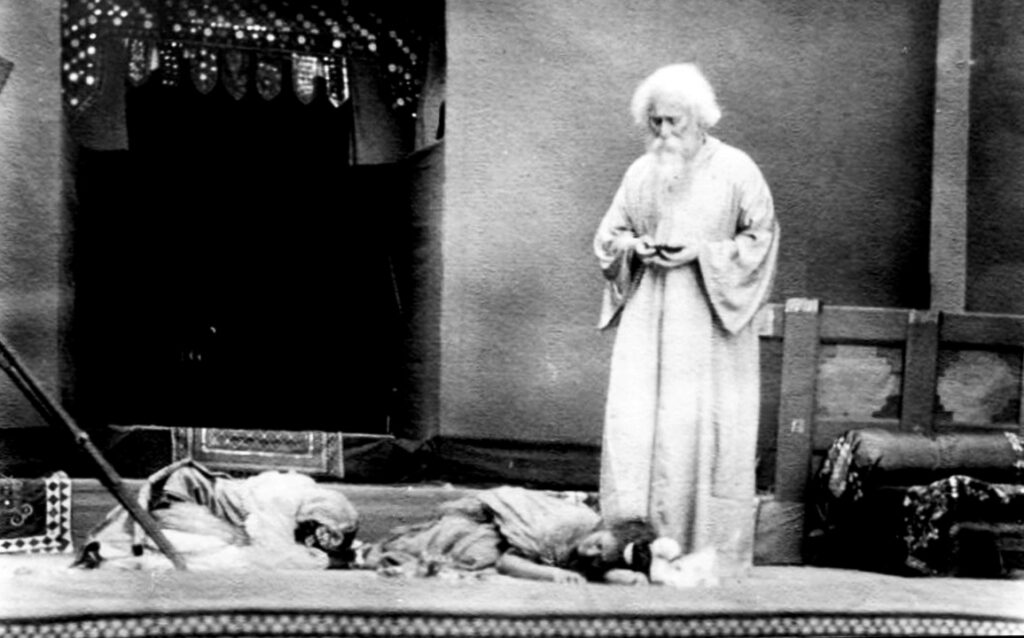

June 2012 was witness to an exhibition of still photographs of Tagore’s sole film Natir Pooja inaugurated by Tagore historian Rudraprasad Chakraborty, Amita Dutta, Tagore archivist and curator Arun Kumar Roy and Sushobhan Adhikari. In January 2013, an unusual and only tribute was paid to photographer Purnendu Bose who did the still photography for Ray’s Sikkim Bose was visibly overwhelmed because no one had acknowledged his contribution till then.

In February 2013, Sardar, continuing with his work on 78 rpm records organized an exhibition on female voices on gramophone records. Select records of the singers were played for the audience, while the lyrics of two songs of each singer were displayed alongside their portraits. The list included Rani Sundari, Manada Sundari, Uma Basu, Rajeshwari Dutta, Suprabha Sarkar, Sahana Devi and Bijoya Debi (Satyajit Ray’s wife). The names cut across social strata and class, merit and talent overcoming other social stigmas. Many singers came directly from theater, the jatra and films because in the absence of playback, most leading ladies had to sing their own songs. Kanan Devi, Angurbala, Binodini Dasi, Bedana Dasi, Niharbala came from films but were recognized for their musical talents too and included in the exhibition.

Under the auspices of the Baudhha Dharmankur Sabha, Sardar also exhibited Chitre Tathagata, with his 110 digitally restored prints of paintings collected from rare magazines, books and photo albums of 19th and 20th Century on the life of Tathagata (Buddha) in 2014 at Kripasaran Hall in Kolkata. A similar exhibition was held the same year to celebrate Buddha Purnima at Shanti Niketan’s Rabindra Bhavan.

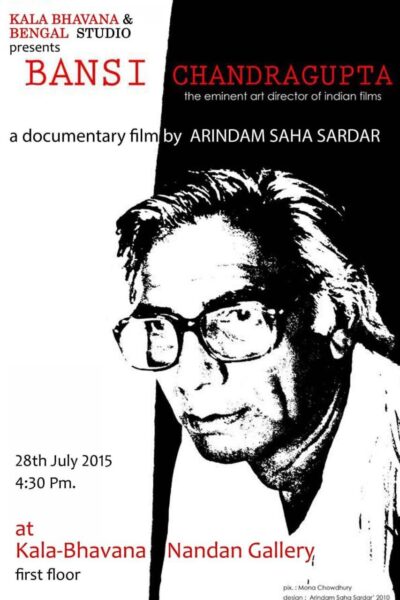

Besides buidling his collection and curating exhibitions, Sardar has also produced and directed three documentaries – Soumendu Roy, Subrata Mitra and Bansi Chandragupta – all key collaborators with Sayajit Ray. The films were self-financed with help from his mother and friends. His most challenging work is Bansi Chandragupta because getting footage and material was difficult. “I make documentaries and curate exhibitions because (a) I never studied film or art or printing formally and this was an intensive learning process guided by Souemdu-Sir and (b) I felt these films and related exhibitions would help people like me who cannot afford the expense of formal training to learn the techniques of filmmaking.” he elaborates.

In Soumendu Roy and Subrata Mitra, the films, one discovers the difference between mapping the life of a living technician on celluloid and documenting the work of a genius who is no more. The ghost-like figure of Satyajit Ray is seen hovering around both the filmscapes. Subrata Mitra is more of a biographical documentary while Soumendu Roy is more a technical lesson than a biographical documentary from a first person perspective. The opening frame is mounted against a Mitchell camera which Roy began his journey with. One can hear the whirring sound of the reel turning as the credits come up. The film then pauses on an Arriflex to close on digital camera, finally closing on the strains of Alo Amar Alo reflecting on the man who has painted with light all his life.

“While researching my documentary on Soumendu Roy, I collected entire albums of working stills of Soumendu-da with Satyajit Ray. He gave everything away to me such as filters, negatives, light meters and eight movie cameras including two 8mm cameras. I restored the photographs. He was overjoyed to see the quality of the restored prints. I felt, why not hold an exhibition of these restored prints? This led to my first exhibition of photographs on Soumendu Roy following the documentary,” Sardar reminisces.

Jibansmriti Archive’s another initiative is the preservation of Bengali theater Production. It began with the play Bhaanu presented by theater groups Mukhomukhi and Tritiyo Sutra, and directed by Suman Mukhopadhyay. The archive has also held an exhibition of posters of plays the great actress Tripti Mitra had acted in and directed as a tribute to her centenary.

Though he has done a remarkable job with extremely limited resources so far, Sardar acknowledges that this will not be sufficient in the future. To maintain and preserve the archive and to enhance the infrastructure in the days to come, Sardar needs external funding as the archive storage needs to be ugraded with modern preservation methods while creating dedicated exhibition spaces for displaying significant works of art and literature. To find out more about Sarkar and the Jibansmriti Archive – you can visit its website here – https://jibansmritiarchive.com/

Header photo: Rabindranath Tagore in Natir Puja (1932). All photos courtesy Arindam Saha Sardar and the Jibansmriti Archive.