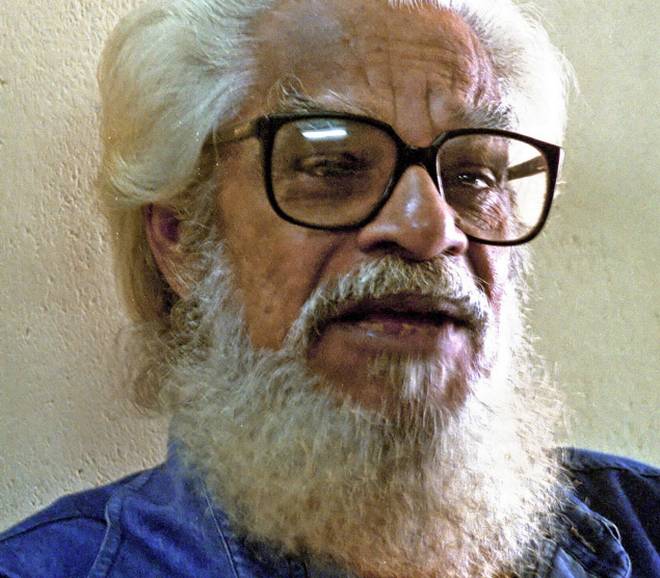

For PN Menon, cinema was life. He spent most of his lifetime in cinema, and was not only a great director, but also a trendsetting art director and poster designer. He was also instrumental in introducing several artists who made their mark in later decades.

PN Menon’s filmmaking career spans more than three decades and 23 films – his most productive years were between 1965 the year in which he made Rosy and 1988, when he made his last significant film, Padippura. In between he made several significant films like Olavum Theeravum (1970), Kuttyedathi (1971), Chembarathi (1972), Gayathri (1973), Chayam (1973) and Malamukalile Daivam (1983).

Born in 1926, Menon left home in his teens and sought refuge in Madras and worked his way through the film industry to create a space of his own. From the beginning, he was very much part of the ‘mainstream-commercial’ industry, yet his films relentlessly struggled with it, experimenting with the processes of production and trying out new ways of narrating a film story. He, for one, liberated Malayalam cinema from the claustrophobic world of the studios and sets. Till then, even when the films told rural ‘malayalee’ stories in films like Neelakuyil (1954) or Rarichan Enna Pouran (1956), due to several technical and other constraints, the whole ambience had to be built in the form of elaborate sets. This gave a very ‘stagy’ look to the films of that period. In Rosy, and later, in a much more definitive way, Olavum Theeravum (Waves and the Shore), PN Menon used natural lights, surroundings and locations as the setting for his film. This was indeed a revolutionary attempt that, apart from bringing cinema to Kerala in real terms, also gave the films a kind of uniquely indigenous charm and feel.

Olavum Theeravum is a landmark film and clearly makes a break with the preceding era which employed a largely theatrical language in dialogue rendering, its mis-en-scene, composition of frames, the body language and movement of the characters. Even the montage and the transitions from shot to shot and scene to scene had their moorings in theatre. With Menon, there was an attempt at freeing the camera from the confines of the theater stage and having a keener sense for visuals. The latter is also evident in the thousands of film posters that PN Menon did for Malayalam cinema. They have a very different visual feel and a greater sensitivity towards use of letter styles and layout. Obsessed with film content and stardom, PN Menon’s contributions to Malayalam cinema as an art director and poster designer have often been ignored. He, in fact, made his entry into Malayalam cinema as an art director in Ninamanija Kalpadukal, directed by NN Pisharoty, which won Silver Medal at the national level.

In Kuttyedathi, PN Menon’s imagery matches with MT Vasudevan Nair’s scenario bringing out one of the most brilliant female performances in Malayalam cinema by KPAC Vilasini in the lead role. While many of the directors who based their films on MT scripts were obsessed with the dialogues, Menon, here brings to life the bleak and degenerating Nair taravad where Kuttyedathi’s life is left to languish. Both in Olavum Theeravum and Kuttyedathi, one can find brilliant use of natural light to capture the melancholic mood of a Kerala village – its verdant landscapes and foliaged exteriors, and also the dark innards of the rural households.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=byOmX-wj8QE

In Chembarathi and Chayam , PN Menon takes a look at urban life of the youth. These films are filled with young, restless men, who are rootless and seem to yearn for something beyond. This semi-urban alienation is something that spurs their creativity, sometimes pushing them to lust and violence. The individual’s irrepressible desire to possess, the struggles that it pushes one into, the strains that it creates on the social fabric etc are some of the abiding themes of PN Menon films. Interestingly, the world his characters occupy is an enclosed one; they try to escape the prison, but often to no avail. The lovers in Olavum Theeravum never realize their dreams of getting married and living happily away from that riverside village; Kuttiedathi’s world inexorably shrinks with her advancing age; in Chembarathi the nymph in the middle of all the men in that lodge where a group of youngsters stay is finally sacrificed, she is not saved by the silent love of the poet, but is destroyed by the lust of the dandy. The love of the Brahmin woman in Gayathri, who is imprisoned by the tradition-bound agraharam, is lured by the call of the outside world but is doomed from the beginning. This restless struggle from within a closed and rule-bound world and the yearning to break free from its clutches, in a way, captures the life and art of PN Menon.

Unlike other ‘independent’ ‘art’ filmmakers of the period, PN Menon’s struggles and successes were not outside or despite of, but from within the system and the industry. Trained, honed and educated only by the industry, yet he never let the system, at least in his early years, to tame him into yet another producer of predictable and predigested film narratives. Working his way through it, he carved a niche for himself, grappling with a variety of its elements – location, milieu, actors, situations etc trying out something new and surprising every time. He was not part of the ‘official’ new wave nor was he comfortable within the power structure of the ‘industry’. He always dared to make films he liked, making them until the end of his life, which is what makes him different from others, who made films for others and not for themselves.

Menon passed away in Kochi on September 9, 2008.