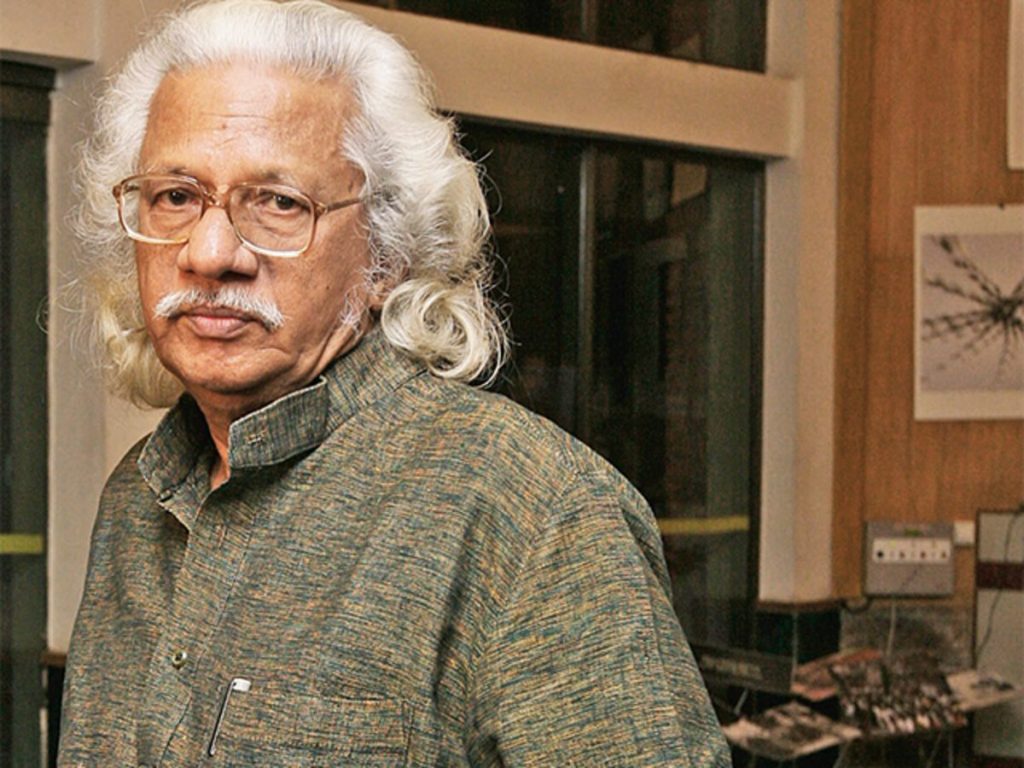

After Satyajit Ray, Adoor Gopalakrishnan is perhaps the most well known Indian filmmaker in the West. He has never compromised with market pressures or audience demands for mainstream entertainment and has held on to his own cinematic language, style and approach that has made him a name to reckon with on the map of International cinema. His films, made in the Malayalam language, have been screened at all major film festivals worldwide to much critical acclaim. He has served as a jury member on various International film festivals besides heading the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) of India and serving as Chairman of the Governing Council at the Film & Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune. His life and films have inspired various documentaries made on him – including one by another reputed Indian filmmaker, Girish Kasaravalli. Many critics and authors have written entire books on him including Suranjan Ganguly, Parthajit Barua and Gautaman Bhaskaran besides collections of essays on him and his films by Lalit Mohan Joshi and CS Venkiteswaran. This is apart from various books on Adoor in Malayalam by different authors.

Born on July 3rd, 1941, Adoor takes his name from the region he comes from, Adoor, part of the Pathanamthitta District in the South Indian State of Kerala. A graduate in Economics, Political Science and Public Administration, Adoor left his job as a Government officer to take admission the Film Institute of India (today the FTII), Pune in 1962. He graduated from there in 1965, with a diploma in Cinema, specialising in Screenplay Writing and Film Direction. Thereafter, going back to Kerala, Adoor was one of the pioneers – others being his friends and colleagues – who established the first Film Society in Kerala, the Chitralekha Film Society.

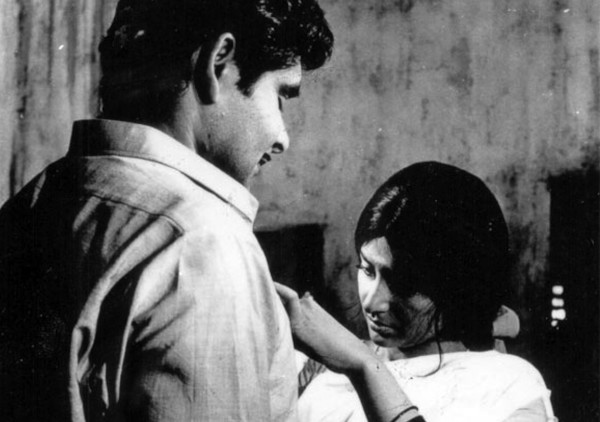

After making a series of documentaries, Adoor finally came out with his first feature film in 1972, Swayamvaram. The film proved to be a landmark film in Kerala and announced the arrival of the ‘parallel cinema’ movement in Malayalam. It is regarded as one of the finest works of the period with several film critics and film historians agreeing that it heralded a new age in Malayalam cinema. Quoting CS Venkiteswaran, “The film, about the uncertainties and apprehensions of the middle class and the impossibility of choices; about the ‘intellectual crisis of the middle class’ and their ‘trip from illusion to reality’, stays in one’s mind due to its economic, evocative and beautifully dense images. Mankada Ravi Varma’s cinematography and MB Srinivasan’s music have a wonderful sparseness and simplicity, lending a haunting quality to them.” Swayamvaram went on to win four National Awards – for Best Film – the second Malayalam film to win top prize after Ramu Kariat’s Chemmeen (1965), Best Direction (Adoor), Best Actress (Sharadha) and Best Cinematography (Mankada Ravi Varma).

For Adoor, “Filmmaking is not just about story telling. That’s a minor excuse, a simple but significant excuse to keep an audience engaged in a cinema theatre. More than that, I am making them experience and also look for many things within and without themselves, and around themselves. I am talking about my kind of cinema. This, I think is the function of the art, any art for that matter – to make you aware, to make you think and disturb you positively and creatively, to make you excited about it, to make you responsive to things.”

Adoor’s reluctance to identify himself with an ideology, his explorations of the individual, often on a one-to-one basis that spans several layers of the human experience and his insistence on the autonomy of the form in cinema distinguish him from most of his peers, and often make him a subject of controversy. This is principally because he belongs to Kerala, forever a volatile political state with polarized agendas preached and practiced by a segmented audience. His oeuvre in cinema explores the interconnectedness of human beings placed within different contexts, some sourced from literature and some springing from original ideas to unfold in layered ways, the struggle or lack of struggle in men and women within specific time-space paradigms. His cinema is unique because of his gift for understatement marked nevertheless by razor-sharp, scathing indictments on feudalism at its worst, patriarchal dominance, capitalistic exploitation sometimes dotted with a movement towards egalitarian thinking, an idealistic, democratic approach to life and emancipation.

Following Kodiyyetum (1977), which won two National Awards for Best Feature Film in Malayalam and Best Actor for Bharath Gopi, and 5 Kerala State Awards for Best Film, Director, Story, Actor and Art Direction, Adoor went on to make what many regard as not just his greatest film, but one of the finest Indian films ever made, Elippathayam or The Rat Trap (1981). The film, set against the decaying feudal set up in Kerala, deals with the tragedy of an idle, lotus-eating man who exemplifies selfishness, personal failure and subtle violence in a way that destroys the lives of those he lives with. Quoting film critic, Martin Teller, “This movie really crept under my skin from the get-go. It mixes a placid mood with light humor and ominous, haunting dread. I’m not entirely sure what to make of all of it — the ending alone raises many questions — but that’s often the sort of film I’m drawn to. It’s a wonderful movie that I don’t think I’ll soon forget, potentially one of my new favorites. Very nice cinematography with simple but thoughtful compositions and vibrant use of color, and the soundtrack, as mentioned, is quite offbeat. Excellent performances as well, particularly Sharadha.” The film was screened at the Cannes Film Festival of 1982 and bagged the Sutherland Trophy at the London Film Festival that year. It also won the British Film Institute Award for the Most Original and Imaginative Film. Back home the film picked up National Awards for Best Film in Malayalam and Best Audiography and the Kerala State Award for Best Film.

His next film, Mukhamukham (1984), encompasses about 15 years in the Kerala’s chequered political history when the left had been in and out of power, the party had thereafter split into two factions and the idealism of the times had eroded as much as his protagonist, a dedicated worker of the Communist Party. In spite of the film’s inherent political content, Adoor does not identify himself or his films with any agenda, political, cinematic, or otherwise. “I do not approve of direct political statements because they are one-dimensional. A metaphor offers me more potential to be creative. Through it, I can comment more effectively about the senseless violence around us today. My objective is to draw the maximum out of the film medium. This exploration does not presuppose a signification, though it does not exclude suggestions, gestures. If it renders itself to an identifiable social message, it is for the reader who may have read it. I did not mean it. In my way of looking at things, all I can say is that they often mistake the incidental for the essential,” he elaborates.

While Mathilukal (1989), focussing on the relationship between a male prisoner (Mammootty) and an unseen woman prisoner (voiced by KPAC Lalitha) in the next compound separated by a high wall, was based on an autobiographical novel of the same name by Valkom Muhammed Basheer, Naalu Pennungal or Four Women (2007) and Oru Pennum Randaannum (2008) were adapted from the stories of Takhazi Shivasankara Pillai whose stories formed the base for Adoor’s wide reading of fiction since his growing years. He says, “I grew up reading his short stories and novels. He wrote more than 400 short stories and over 40 novels. Chemeen was based on one of his novels. Most of his well-known novels have been adapted to films. His short stories have been powerful as well. Thakazhi wrote mostly about Kuttanad, an area of backwaters and rice fields where he was born and where he lived practically all his life. His writings have been largely about this land and its people. No wonder, they are very authentic and true to life apart from being very insightful. I re-read all his works a couple of years ago with the idea of finding interesting material for a film. Instead of one, I found stories for two films. For Four Women, I have kept the stories independent of each other and at the same time worked on an internal thematic connection between them – that of a growing awareness amongst women.”

Pinnayum (2016), Adoor’s last feature film till date and his first shot in the digital format, on forced migrant labour and the shocking effect a man’s disappearance can have on the surviving family, has not been written about much as it is considered as one of his relatively weaker films and said to be lacking Adoor’s ‘signature’. He has recently made a short film called Sukhantayam or The Happy End (2019), which was a little different from his other films in the sense that it dealt with the novel theme of suicide in a very satirical and humorous way. The Happy End Limited is a small firm that actually counsels clients not to commit suicide in exchange for a registration fee. It is a firm set up by three men of different ages and status headed by a post-graduate in psychology. The 30-minute film offers a delightful spoof on the romanticizing of suicide by most suicidal victims.

Adoor’s other important feature films include Anantaram (1987), Vidheyan (1993), Kathapurushan (1995) – winner of the National Award for Best Film, and Nizhalkuthu (2002).

Apart from his feature films, Adoor has also made several shorts and documentary films, most of them focusing on and feeding off his lifelong passion for the performing arts. The short films and documentaries, he laughs, helps in keeping the home fires burning while feature films are being ‘explored and thought about.’ He adds that his documentaries on Kathakali and Yakshagana performers and dance styles evolved into a learning process for him. “This was one opportunity for me to learn about them in depth and also get inspired by them. It was a great, refreshing experience. In a very strange, indirect way, it invigorated me. I got greatly enriched. It expaneds my understanding of my culture, my living and ultimately, myself.”

The Awards in Adoor’s cinematic journey have been plentiful and well deserved. “Awards are important particularly in the early days of one’s career, because it tells you in some way that what you are doing is worthwhile. If there is appreciation and substantial recognition, it helps a filmmaker. Awards are a kind of understanding from others about your work. Yes, awards are very important.” he says.

All the films Adoor has directed, from Swayamvaram to Oru Pennum Randanum have won him several National, Kerala State and International awards. He was awarded the British Film Institute Award for Elippathayam which dealt with the tragedy of an idle, lotus-eating man who exemplifies selfishness, personal failure and subtle violence in a way that destroys the lives of those he lives with. The film also bagged the Sutherland Trophy at the London Film Festival in 1982. He has also won FIPRESCI prizes besides awards at the Venice, Karlovy Vary, Toronto International Film Festivals among others. In 2003, the French Government honoured him with the Commandeur Des Arts et Lettres Order for his outstanding contribution to cinema. NETPAC (Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema) bestowed the Lifetime Achievement Award to Adoor at the International Film Festival of Colombo in 2015 for his contribution to cinema. He has also been honored with the country’s highest Cinematic Award, the Dadasaheb Phalke Award. for his rich contribution to Indian cinema in 2004, besides the Padma Shri (1984) and Padma Vibhushan in 2006.

His wife having passed on some years ago, Adoor now lives alone in his beautifully decorated bungalow with a garden on the outskirts of Thiruvananthapuram in Kerala.