The magnificent obsession with the silver screen is a continuing saga of fatal attractions, endless struggles, frustrations, gambles, thrills and shattered dreams. Drawn to the magic lantern, many of these dreamers burn their wings. Some, after a brief spell of stardom, are relegated to the backstage of oblivion. A few are immortalised; but many are immolated. Unable to wrench oneself free from its spell, many fall by the way side resorting to nostalgic memories and unfathomable bitterness.

The story of cinema all over the world was also the history of such heroes and heroines drawn to the flame of passion, fame, lucre and immortality. The history of Malayalam cinema is also replete with stories of the blood, sweat and tears of the pioneers of Malayalam cinema like Katturkaran Varunny Joseph, JC Daniel, R Sunder Raj, Muthukulam Raghavan Pillai, K Gopinath, Alleppey Vincent, KV Koshi, MK Kamalam, CK Rajam, K Aroor, and AB Pious. They gave everything to cinema. Recorded history that transpires from generation to generation, seldom remembers the ones beyond the pale of the limelight – those sagas of frustrated dreams, unfinished projects, exploited lives, and life-as-stake gambles.

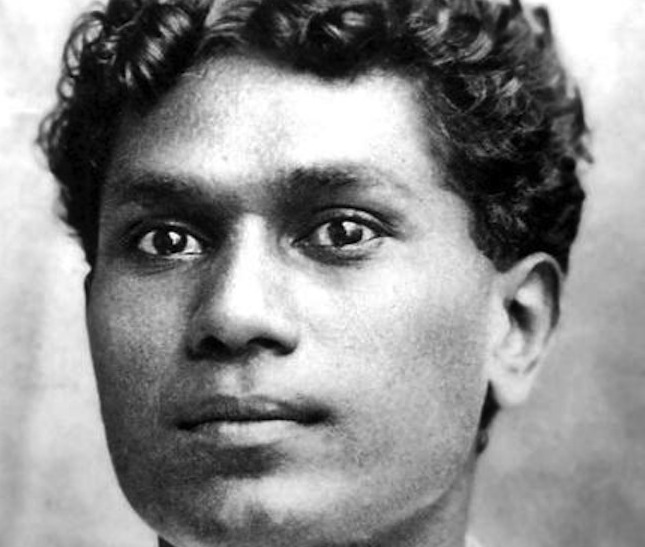

The story of JC Daniel, the father of Malayalam cinema, was typical of a pioneer, who dreamt beyond his times. His life too was one of great passion for cinema, in other words a saga of relentless struggles and frustration, dreams and tears that lie beneath the luminous surface of the iceberg that is cinema.

JC Daniel was born in Agastheeswaram (Kanyakumari District) on November 28, 1900. Right from childhood he was interested in martial arts, especially kalaripayattu, which he learned and excelled in. His passion for the martial arts spurred him to document it for the world and preserve it for posterity. (In many intricate ways, passion for cinema is linked to the passion for immortality, the yearning to immortalise oneself and the present). At the age of 22, he wrote a book in English,Indian Art of Fencing and Swordplay. But he was not satisfied with that, for he was looking for something much more enduring and magical. When he came across cinema, he realised its potential to realise his dream. From then on all his energy and resources were spent upon making a movie documenting the art. This idea led him to another passion -the passion for cinema.

He plunged into it and made enquiries about film production, and went to Madras and later to Bombay to learn the techniques of cinema. In Madras, he was not allowed inside any of the studios. But unfazed by the bitter experiences, he manoeuvred himself into a studio in Bombay by feigning as a schoolteacher eager to see one of the wonders of the world. Back home he sold his ancestral property and in 1926-7, established the first ever film studio in Kerala at Pattom in Thiruvananthapuram city. It was called The Travancore National Pictures.

By then, he had also changed his strategy. His visits had convinced him that feature films were the in-thing. Leaving aside the idea of a documentary, he wrote a script with a lot of fights and Kalaripayattu scenes (the traditional martial arts of Kerala) in it. When Daniel was contemplating Vigathakumaran, Indian cinema was only a decade and a half old and had not yet entered the ‘talkie’ era. Only a few pioneers like DG Phalke, Baburao Painter, Kanjibhai Rathod, Dhirendranath Ganguly, Manilal Joshi, Bhalji and Baburao Pendharkar had entered the field. In the South, Tamil cinema was still in its infancy, with only a few mythologicals to its credit.

Daniel was also a trendsetter in Malayalam cinema. While other vernacular cinemas were rediscovering mythologicals through the new medium, Malayalam cinema, from the beginning, strode a different path. The themes of the first films in Malayalam like Vigathakumaran and Balan (the first talkie, made ten years after Vigathakumaran) were secular and social.

Vigathakumaran had all the ingredients of cinema: fights, coincidences, love, accidents, parting and reunion, and a happy ending. Ironically, The title Vigathakumaran holds ominous resonance now, the word literally means the lost boy or one who is with the lost boy. Its storyline with various coincidences, narrative twists and turns, goes as follows: Chandrakumar, son of a rich man in Thiruvananthapuram is kidnapped by the villain, Bhoothanathan, and taken to Ceylon. The efforts of his parents to find him do not succeed and Chandrakumar is brought up as a labourer in an estate. The estate owner, who is British, takes a liking to him and in time, Chandrakumar rises to the post of Superintendent. At this time, Jayachandran, a distant relative of Chandrakumar happens to come to Ceylon. Incidentally, he is robbed of all his belongings by Bhoothanathan. Stranded, he gets acquainted with Chandrakumar and they become close friends. They come to Thiruvananthapuram where Jayachandran’s sister falls in love with him. Meanwhile, Bhoothanathan attempts to kidnap her and the duo’s timely intervention saves her. A scar on the back reveals Chandrakumar’s identity which eventually leads to the happy reunion of the family.

Daniel had to go through all the painful travails of a pioneer to realize his project. To get a female to act in a film was itself a great task in those days. As it was a period when female roles in even theatre were played by males, Daniel had to go all the way to Bombay to bring one Ms Lana to act in his film, that too for a fabulous amount of Rs 5000!. But once she arrived at the Pettah railway station in Thiruvananthapuram, she refused to step out unless there was a car to take her to the place of stay. Cars, at that time, were rare and according to reports, in the city only the Maharaja and Marikar, a businessman had a car of their own. But nothing would stop Daniel. He managed to get Marikar’s car to take her home. But it was only the beginning of his problems. Her stay was the next headache. She wouldn’t stay in the house he had arranged. And she would stay in no less a place than the one like Kowdiar palace (the palace of the Travancore Majarajas), which she saw on the way! Daniel was at the end of his wits. And worse, before the shooting started Ms Lana left the film. Daniel went on with his search and finally managed to find a local girl – Rosy – to play the role. Accounts differ as to her identity. Some say she was an Anglo-Indian; according to others, she was a scheduled caste labourer from Thycaud.

Against all odds, Daniel completed Vigathakumaran in 1928 – the first ever film from Malayalam. The film premiered at Capitol, opposite the present day AG’s office near the present day State Legislature Building in the centre of Trivandrum city. But the audience would not tolerate a local woman on the screen! During the show, the audience started hooting and shouting her name. In a scene where the hero picks a flower from her hair and smells it, the audience went berserk, throwing stones. The screen was torn and the screening had to be stopped. The wrath of the audience did not stop there. According to reports, the attacks continued on her person and her house was burned down. Eventually, unable to stay in Trivandrum, Rosy had to elope with her lover to Tamil Nadu to escape her celluloid image.

Though Vigathakumaran was screened at various other places, it was not a commercial success. Despite the setbacks, Daniel went on to make one more film, this time a documentary on martial arts, Adithadi Murai. But by that time, his debts had mounted, forcing him to dispose all his assets including the studio. Almost a pauper, he left Trivandrum to seek a livelihood. Daniel’s life after that was one of loneliness and a struggle to make both ends meet.

In a bid to turn a new leaf in his life, he sold his wife’s property to go to Bombay and take a BDS degree. For the next three and a half decades, he worked as a Dental Surgeon at several places in Tamil Nadu (mostly in Palayamkottai, Madurai and Karaikudi). He was never to return to cinema. Nor did his economic status ever allow that.

Though Malayalam cinema made huge strides during his lifetime, the pioneer who sparked it all, lived a life of obscurity and penury. Having suffered a paralytic stroke and having gone blind for the last 8 years of his life, his last days were lonely and painful. Forgotten by all, he died a miserable death on April 29, 1975. At the fag end of his life, he had told R Kumaraswamy, the editor of the popular Film Magazine, Nana: “Malayalam cinema is a thriving industry now. But never have anyone bothered to recognise me as someone who made a film all by himself in those days. As for the new generation, they don’t know me. But it is not their fault, I soothe myself.”

Sadly, the prints of both the films have not yet been traced. Only a few are alive who have seen Vigathakumaran. Like Daniel, Vigathakumaran also lives at the edge of oblivion and in the memory of but a handful of people. As an afterthought or penance, the Kerala State Government constituted the highest film honour of Kerala in his name, the JC Daniel Award.