The phrase Revolutionary Feminist Politics, so fashionable today within creative fiction and non-fiction in all languages, did not exist in the vocabulary of Indian literature when Ismat Chughtai began to write. She became one of the first women writers to have this appendage attached to her name unwittingly. She did not quite care for such appendages before or after her rise to fame. That does not change the fact of what is now considered history. A glimpse into her life will offer a ring-side view of what courage can mean to a woman who was born much before her time and turned Urdu literature on its head for all time who did not falter in her steps despite severe criticism by both readers and intellectuals.

Born on August 15, 1915, Ismat Chughtai’s life story is more exciting than some of the films scripts she wrote during her career in Bombay where her husband, Shaheed Latif, was a filmmaker of some note. The ninth of ten children with a progressive thinking civil servant as father, Ismat told her father in no uncertain terms that she wished to go to school instead of learning to cook. She wrote directly to the man her marriage was fixed that she had no intention of marrying him because she wished to study further. She was hauled in a court case for her short story Lihaaf (1942) for obscenity and decided to fight instead of tendering an apology. Her lawyer argued that there were no explicit references to homo-eroticism in the story and hence she could not be accused of obscenity. The case was dismissed.

Lihaaf (The Quilt), deals with a lesbian encounter within an all-woman setting in a traditional Muslim household. It courageously fleshes out female sexuality within a lonely and beautiful young woman who yearns for her husband’s love. Written in 1942, The Quilt remains a landmark in Urdu short story writing. A frustrated housewife, whose Nawab husband has no time for her, finds sexual and emotional solace in the company of an ugly female servant. Written many years before the term ‘lesbianism’ entered the vocabulary in India, the story unfolds from the point of view of a girl child who hides under the bed of Begum Jaan and wonders what the two women are doing under a quilt that keeps moving forever. Sadly, Deepa Mehta’s Fire, said to have been inspired by Lihaaf, stands very poorly in comparison with the original which not only takes serious pot-shots at the complete ghettoization of women cutting class divisions within the Muslim feudal stronghold occupied entirely of women in confined spaces, but also takes a bold step towards sexual fulfillment of a different kind.

Chughtai was born in Badayun, Uttar Pradesh and grew up in Jodhpur. They were six brothers and four sisters. Her sisters were married off when Ismat was a child and her childhood was mostly spent in the company of her brothers. This contributed considerably to her forthrightness and to the spontaneous nature of her writing. One brother, Mirza Azim Beg Chughtai, who was already an established writer was her first teacher and mentor. She studied in the Women’s College of Aligarh Muslim University and is the first Muslim woman to have attained two degrees – a BA and a BEd.

Her husband, Shaheed Latif, encouraged and helped her every bit of the way in the realization of her dream to become a great professional writer and they collaborated on many films together. She was considered a liberal and even by today’s standards, she sets an example in the sense that her daughter married a Hindu and a nephew followed suit.

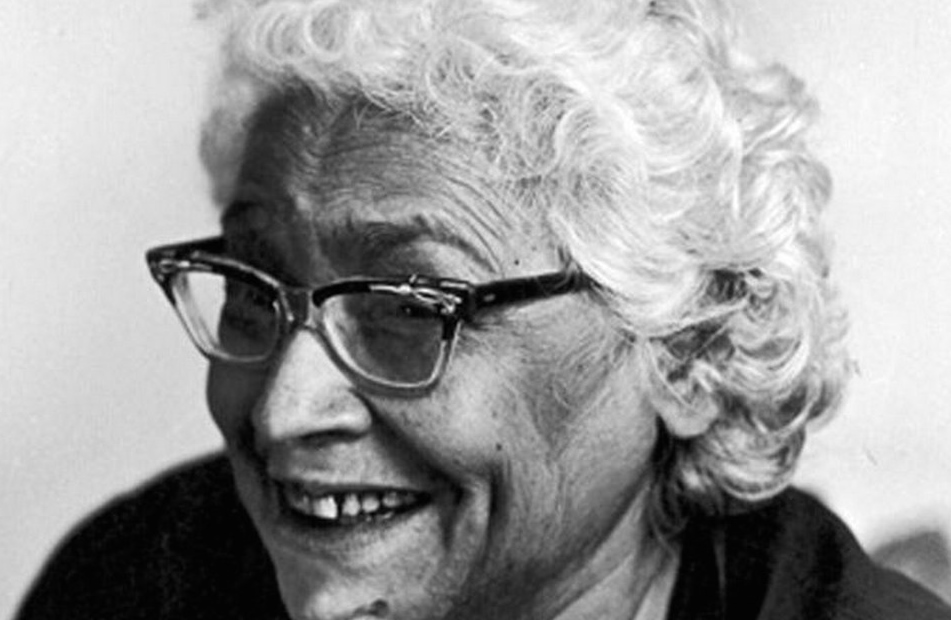

“The pen is my livelihood and my friend, my confidante, a walking talking friend in my hours of loneliness. Whenever I want I can send for anyone via the pen’s flying carpet, and when these people arrive, I can say anything, make them cry, laugh, or reduce them to ashes with my harsh words. And if I feel like it, destroy them by tearing them up into innumerable tiny fragments…” she wrote in Yahan se Wahaan Tak. In her formative years, Nazar Sajjad Hyder, a noted Urdu litérateur had established herself as an independent feminist voice, and the short stories of two very different women, Hijab Imtiaz Ali and the progressive Dr Rashid Jehan were a significant early influence on Ismat. She strongly believed that the Naqaab Muslim women wear, should be discouraged because it is oppressive and feudal. Many of her books have been banned at various times during their publication history. She did not wear the naqaab herself and wore her hair short in a curly bob, and smiled easily.

Early in her career, Chughtai was associated with the Progressive Writers’ Association. In her stint with films, she made a documentary called My Dreams in 1975 and two feature films, Fareb in 1953, co-directed with Shaheed Latif, and Jawab Ayega in 1968. She also played a rather effective cameo in Shyam Benegal’s period classic Junoon (1978) based on Ruksin Bond’s novella Flight of the Pigeons, which won a string of awards from Filmfare and at the National Film Awards. She wrote the screenplay and also produced Sone Ki Chidiya (1958) directed by Latif, which featured Nutan in the dramatic role of a very poor girl who runs away from her exploitative relatives and becomes a great star in Hindi films. The film,said to be on the based on Nargis’ life, did not do well commercially but had a powerful script with lovely music by OP Nayyar and singer Talat Mahmood doubling up as the villain. Chughtai also collaborated with Latif, for Dev Anand’s star making film, Bombay Talkies’ Ziddi (1948) and wrote the screenplay and dialogue for his Arzoo(1950) as well.

Chughtai won the the Best Story Award from Filmfare in 1975 for MS Sathyu’s masterpiece, Garm Hava (1973). The film was based on an unpublished short story of Chughtai’s that was adapted by Kaifi Azmi and Shama Zaidi. Other awards that came her way are the Ghalib Award for her Urdu drama Tehri Lakeer (The Crooked Line) (1974), the Soviet Land Nehru Award in 1982 and the Iqbal Samman Award from Rajasthan Urdu Akademi for the year 1989.

In a moving centenary tribute, Tahira Naqvi, noted Urdu writer and translator of Chugtai’s works, writes: “Ismat Chughtai, the Grand Doyenne of Urdu fiction, the woman who married a film director, who wrote screenplays and made films, who cooked up a storm for friends and family with the same gusto as she wrote bold, inhibited, and memorable fiction, who said she was a mother first and a writer second, and about whose style Krishan Chander, the well-known Indian writer, said, “… her (Chughtai’s) afsana makes us think of … a horse race … [there is] swiftness, movement, speed, alacrity … the asana appear to be running … the sentences, symbols and metaphors, voices and characters and emotions and feelings … springing and moving forward with the speed of a storm…” is unfathomable in the scope of her writing and her life.” Sukrita Paul Kumar and Sadiq edited a wonderful collection of essays and articles on different aspects of Chughtai’s life and writing in Ismat: Her Life, Her Times. Naseeruddin Shah’s Motley group has staged three short stories by Ismat Chughtai in Ismat Aapa ke Naam, one of Motley’s most popular plays.

Ever the liberal, Chughtai is said to have requested that she be cremated instead of buried after she passed away. She was cremated at Bombay’s Chandanwadi crematorium but the story goes that some of her remains were later buried.

She might have passed away on October 24, 1991 but women like Ismat Chughtai never die. They live on through their writing, their revolutionary ideology and their life.