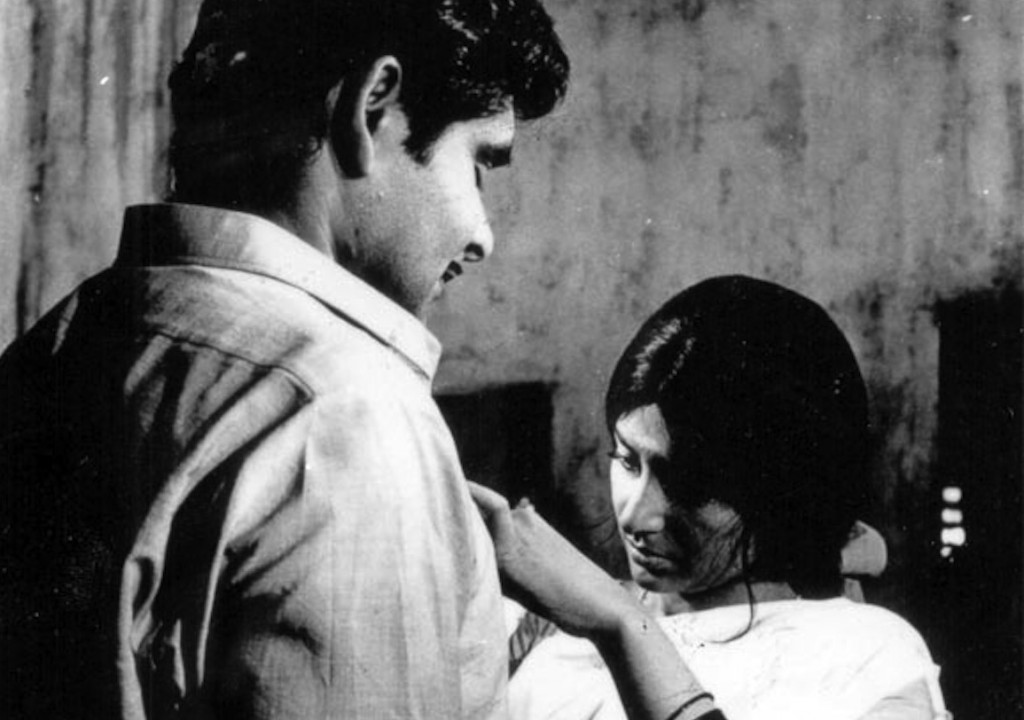

Viswam (Madhu) and Seetha (Sharadha) elope and come to the city. There, economic presseures make their survival tougher and tougher. They move from their expensive hotel to a cheaper one and then finally to a slum where a smuggler, prostitute and a rice seller are their neighbours. Viswam, a writer, has his novel rejected and loses his job as a lecturer. He dies in poverty leaving Seetha a destitute widow with a small baby…

The typical milieu of the Malayalam ‘new wave’ cinema was one that was caught between the past and the future; lacking beliefs and values of the past, and hopeless about the future. It was not satisfied with sloganeering or syrupy solutions like the ones offered by the new cinema in other languages. Instead they reflected the peculiar socio-economic and political situation of Kerala, a society which had relinquished the shackles of a feudal past but was at a loss as to its vision of the future. It was neither agricultural nor industrial. With the land reforms, the joint family system was in shambles, which gave rise to a new sense of self. While its consumption patterns were highly developed, its production base was precarious and highly dependent. By the 70’s the nationalist and Nehruvian dreams had set and the hopes aroused by the communist movement had drifted towards the parliamentary shores and was firmly anchored there, turning it into yet another party. The films of the period capture this confusion and the loss of faith in teleologies amidst the rebellious waves of the socio-cultural ambience of the 70’s (the key words that could evoke the mood of the period being Naxalbari, Vietnam war, Che, Paris Student Movement, Existentialism, Hippie-ism etc). The films of the period, animated by a new sense of self and a yearning for self-expression and freedom, reflect this social and aesthetic turbulence.

In Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Swayamvaram, a film which is acclaimed to have inaugurated the new wave in Malayalam, one can find both these struggles – the struggle for expression and survival, though in the end, the struggle for survival gets preeminence. Swayamvaram begins with a journey – one that marks a big departure from the prevalent notions about cinema, and announces the arrival of ‘new wave cinema’ in Malayalam. It is a typical example for several reasons; it is one of the finest works of the period that several critics have identified as heralding a new age in Malayalam cinema. It was produced by a film society, Chitralekha, and its audience was mainly middleclass intellectuals, students, and the film society buff. Its theme (personal survival and self expression, of choices etc) and style (formally self conscious, dense, slow and ponderous; devoid of songs, stunts and buffoonery), are typically new wave and markedly distinct from the commercial fare. Moreover, it is a love story centred around the nuclear family and its struggles.

In the bus journey at the beginning of the film, there is a miscellany of people inside the bus – bored, dozing and indifferent. For Viswan and Seetha, it is the most important journey in their life – for them, it is a journey from the shackles of the past and into a future of freedom and hope. As a microcosm of society, that bus and the journey represent their life and the society that encompasses them. While the society rattles on in its routine movements, for our protagonists, it is the most crucial – a matter of life and death. This insularity and utter lack of connection and belonging was to characterize the heroes of new cinema. This conception of the middle class as the intense, experiential core of an amorphous mass, also marks a radical shift with regard to the subject the cinema creates and addresses.

This fall and the disillusionment embodied the anxieties and fears of the educated, middle class youth about their life, livelihood, status and self- expression. The couple in the film comes from nowhere; their past is misty (almost irrelevant) and appears only vaguely in the form of nightmares. Nor is their background or nativity specified, again marking a rupture with the past and the native milieu. Cut loose, their identity is not anchored in the past or in their milieu. Obviously, wherever they come from, the life of their choice was impossible there, hence their elopement. Uprooted from one’s space and milieu, they have made a choice of their own (literally ‘swayamvaram’). The opening sequences warmly convey their romantic optimism about a life of freedom – of finding a job of one’s liking, to be successful as a writer, and to immerse themselves in each other without any hindrance.

All the opportunities that come Viswam’s way – the tutorial college, the publisher and the sawmill – turn out to be disappointing. Everything seeps with a sense of stagnation. The tutorial is a sinking ship and its proprietor a failed businessman who is bitter about the past and the present. The chatter at the publisher’s office makes it evident that only the established and the famous matter in the world. It is an elite club the doors of which are closed for upcoming writers like Viswam. The sawmill and its aging accountant seem to have existed there for ages. Only the faces change. Viswam replaces an unlucky man, and after his death, another will replace him also. It is a thoroughly closed world where there is no promise of change.

Politics also holds no promise and the disillusionment with politics is apparent in the scene where Viswan passes by a public political meeting without a faint interest in it. The incident that follows where he is accosted by a sex worker on the street, further underline the middle class ‘exclusiveness’ of the character.

The couple come to the city in search of life, freedom and happiness. But by the end of the film they realize that one’s own choices seldom bear fruit or find fulfillment; their journey has only brought them into yet another cycle of unfreedom. Viswam meets with death and Seetha is left at the threshold of an uncertain future; the door is closed but it is rattling, by wind or a ‘wellwisher’, one doesn’t know. The film is not definitive about either. In the sound track there are ominous suggestions of a storm. The narrative has come full circle, and this time Seetha is alone, and at the threshold of yet another choice. But this time, her choices are limited.

In the film, the external world is actually a threatening presence for Viswam and Seetha. The last scene is a poignant depiction of this relation between home and the world. From the beginning the couple, and later the family, appears like an island fighting to hold itself together in the middle of a society that throbs around them. Everything outside and below them threatens their existence. It starts from the very beginning with those terrible knocks on the door at the hotel, the voice of the drunkards outside and the threat of the pickpockets. A comparison of the subjective viewpoint shots in the beginning and later on in the film will substantiate the point. The early optimism is marked by a number of top angle shots of the couple watching the world ‘below’ them – through the window of the hotel ( a religious procession on the street) and the lodge ( crows atop the tile roof, hotel servant grinding rice etc.). But when they move to a small house in the suburbs, the shots are eye level, and the lower world is menacingly nearer to them in the form of neighbours and ‘well wishers’ (smuggler Vasu, Kalyani the prostitute etc).

The threats continue to haunt them here also. Viswam or Seetha tries to make no contact with the world outside their home, which is animated by lower forms of life. Drunkards, prostitutes, smugglers and other lumpen elements abound there. And all of them stand in sharp contrast to the respectable, middle class life the couple dreams of. The overtures of the smuggler, the drunken threats of the unruly elements, the menacing visit of the policeman etc are glimpses of lower life that threaten the insular security of the middle class life. This threat extends to his workplace and to the street. At the sawmill, Viswam is haunted by the stare of his predecessor (a poignant and memorable performance by Bharath Gopi) whose job he has usurped; and on the street, the invitation of the sex worker scares him. The couple is at ease only in their imagination. The claustrophobic mood of the second half of the film stand in stark contrast to the love sequences in the first half which is all in bright, open landscapes. The mis en scene and the camera movements also reflect the habitus of the couple. Medium shots with a sharp eye for details embody detachment while at the same time lending a sort of contemplative quality to the visuals. Characterizing the relationship of the characters to the world, camera seldom moves or zooms unnecessarily – as if there is a rupture between the characters and the world.

In earlier films, the narrative of the individuals and his struggles were representative and symbolic of the society/class/community they belonged to. It was as if the society was speaking, acting and experiencing through them. But for the new wave films, the society was just a backdrop enabling the portrayal of the protagonist in sharper relief, a sort of mirror to emit and reflect the personal/internal conflicts of the narrative center – the protagonist. And, if earlier, the narratives were about the possibilities of life and the search or struggles for it, now life seems worthless and it is death that tantalizingly offers a sense of fullness or completion.Swayamvaram is replete with suggestions of Viswam’s infatuation with death. At the height of their romantic involvement, he is shown as irresistibly drawn towards death almost as if teasing it. In the romantic scenes that follow their arrival in the city, where the couple frolic in different landscapes, to the despair of Seetha, Viswam suddenly disappears, lies on the railway track as if to commit suicide, descends into the rocky creek beside the sea. The sequence culminates in a shot where the couple are seen lying beside each other on the sea shore, bringing to mind the last scene of a popular hit (Ramu Kariat’s Chemmeen (1965)), where the frustrated lovers find union in death.

When he comes to the city, Viswam has great hopes about making it as a writer. Halfway through the film, it becomes evident that his novel (significantly titled Nirvriti meaning ecstacy) will never be published. It was something that he treasured till then. But in the exigencies of survival his ‘creative’ life is forgotten and there is no evidence of his pursuing it further – marking another internal fall. Evidently his art is the product of ‘tranquility’ and self-expression – a pure and ecstatic endeavour that withers in the sunlight and dust of the everyday life. These notions of creativity and the artist as the obverse of ordinary life are also symptomatic of the period.

Another interesting set of references relate to cinema itself. References about commercial cinema abound in the film, in a way, reflecting the self-consciousness inherent in the new-wave project and enunciating its notions about ‘art’ and ‘creativity’. In the first half, when the happy couple embrace , there are shots of film posters which act as a visual counterpoint to their senseless joy. (which is both a subtle comment about commercial cinema and about the couple’s illusions about life and love.) Another reference appears when Viswam is eagerly sitting at the publisher’s office. In their casual talk, the editor and his friends refer to a successful writer who had made it big in films. The proprietor of the Tutorial college, in better times, was a film producer who went broke when he tried to produce a ‘class’ film. During their drunken talk, there is a snide reference about loose morals in the film world; and when they talk about the actress ‘Jayarani’ a dirty smile illuminates his face. (again a comment upon the film industry and the character). Cinema also pops up when Seetha and Viswan are discussing his novel. While Seetha is averse to the idea of his heroine dying in the end, Viswan doesn’t want his novel to end happily like in films. All these references about literature and cinema in the film are in a way self-referential and point towards notions about creativity and ‘art’ inherent to the new wave project.

Even after so many years, the economic, evocative, and beautifully dense images of Swayamvaram stay in one’s mind. Mankada Ravi Varma’s cinematography and MB Srinivasan’s music have a wonderful sparseness and simplicity, lending a haunting quality to them. One can also find that unique quality that distinguishes all Adoor’s films: none of the characters in his films are ‘minor’. The ‘minor’ roles played by such brilliant actors and actresses like Bharath Gopi, P K Venukuttan Nair, KPAC Lalitha, Thikurissi, Karamana Janardhanan Nair and Adoor Bhavani turn into wholesome characters in Adoor’s films because they belong to our everyday lives.

Swayamvaram remains a landmark film (prophetic in many respects and a trail blazer) about the uncertainties and apprehensions of the middle class and the impossibility of choices; about the ‘intellectual crisis of the middle class’ and their ‘trip from illusion to reality’.

Malayalam, Drama, Black & White