When Prosenjit, the superstar of Bengali cinema, lost his mother, he was restrained by security guards and the police from performing all the rituals that he was ordained to as the only son. It was his sister, Pallavi, who had to do fill in as the police said his presence was becoming a serious law-order-problem. This situation forms the germ of Kaushik Ganguly’s new film, Jyeshthoputro.

The two questions explored in Jyeshthoputro are, (a) what happens to small town residents of Ballabhpur when a superstar suddenly arrives upon the death of a parent and (b) who is really the ‘elder son’ who, as convention demands, has the responsibility of performing the rituals for ten days followed by the shraddha. Is it the chronologically born elder son who lives in a completely different world of glamour and chutzpah and comes to his hometown of Ballabhpur after ten long years? Or, is it really the younger son who has lived with their idealist, Communist, schoolteacher father and taken care of him all these years?For Indrajit Ganguly (Prosenjit Chatterjee), it is a homecoming – never mind that it is a time of grief and mourning. For his younger brother Partho (Ritwick Chakraborty), it is a blend of surprise and sharing in the grief. In the midst of these two brothers is Ilaa (Sudipta Chakraborty), the middle offspring, who is kept locked in a room because she is mentally unstable.

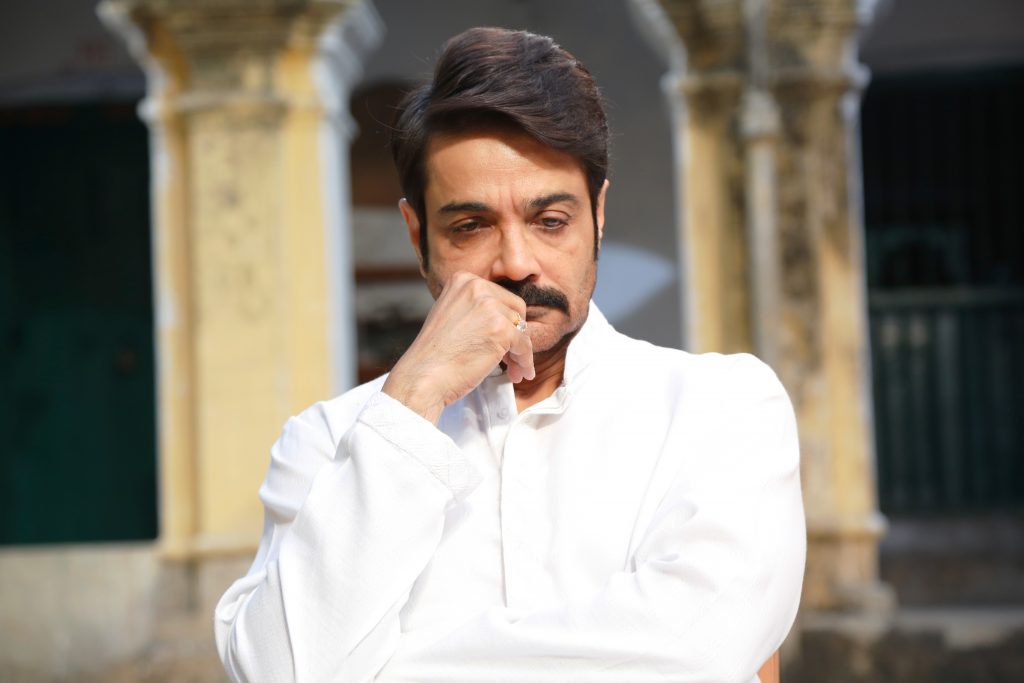

The coming of Indrajit creates a terrible situation outside the ancestral mansion as the townspeople begin to rush in or gather outside to catch a glimpse of the superstar in flesh. He comes and stands on the balcony, waves at them and then says, “Enough, now go home.” He finds it tough to slip out of his star image and step into the reality of being a grieving elder son because the pull becomes stronger on the star side every passing moment. The super star cannot travel alone so he comes in a large van complete with his handyman, driver, an irritating secretary, and a bodyguard. His stardom also places him a lavish bungalow courtesy the CM so he does not actually live in the family home. Partho gets increasingly annoyed, irritated and angry with crowds and even relatives rushing in to spoil the solemnity of the occasion, doubled with the anxiety over his heavily pregnant wife on the one hand and his crazy sister on the other. The crowds define a collective character unto themselves. A cousin sister (Damini Basu) is cloying and absolutely star-struck while the ex-girlfriend (Gargi Roy Choudhury) carries her schoolteacher persona with a rare dignity, entirely unaffected by the charisma of the super star. The director defines great restraint in not going into flashbacks to show how and why the love affair faded away and when and leaves his audience to draw its own conclusions.

In this entirely character-driven story, each single character has a role to play such as the English-speaking secretary with an attitude problem or the handyman who spikes up Indrajit’s drinks or even the distant relatives who have dropped in purportedly for the shradhha but really to catch a selfie with the superstar quite shamelessly. The few scenes of happy camaraderie between Indrajit, the star elder brother and Partho, the ordinary brother burdened with serious financial problems, a wife and a crazy sister are short-lived. As the film moves towards an organically evolving climax, minus any twists, the gap between the two brothers open up, showing wounds that will never heal because they are too deep to be cured. The confrontation between Indrajit and Partho in the former’s guest house with Partho having downed several drinks, is beautifully treated. The juxtapositions of the two brothers function as a true counterpoint in characterisation with Ilaa, the not-normal one ironically becoming the harmonious factor between the two.

Prosenjit gives an outstanding performance not only because he totally identifies with Indrajit but also because he takes care to act beyond himself and beyond the superstar that he is in the film and in real life. The director has given him several silent moments that are more powerful and expressive than dialogue would have achieved. He says a lot with just a look thrown at his sister or getting up to join the schoolteacher in her song at the school’s condolence meeting in memory of his father, or, trying very silently to wipe off the kiss of the cousin with his handkerchief in subtle disgust. These are examples of his brilliant performance where the real and the reel blend ideally. Ritwick Chakraborty is an actor without the glamour of ever becoming a superstar. But it is this very lack of glamour and X-factor that makes him one of the most-in-demand actors in Bengali cinema today. He matches Prosenjit more as a counterpoint than as a brother and shows no inferiority complex for not being anywhere where his star-brother is.

However, these two performances aside, the film is worthy of a watch just for the incredible act of Sudipta Chakraborty as Ilaa, the crazy sister who has her lucid moments. It has taken Sudipta at least two decades to be recognized as an actress par excellence and today, she is making waves with every single film she participates in. This film sees her give one of the finest performances of her career so far.

Prabuddha Banerjee’s music is extremely low-key and one must mention the tasteful use of strains of the Internationale sung in the procession of the dead father, not to leave out the Tagore song that makes the crowds go berserk when Indrajit begins to sing. Tanmoy Chakraborty’s art direction is minimal yet very precise and detailed. Shirsa Ray’s cinematography suits the mood and ambience of the film without going overboard over close-ups and overt emphasis on every scene, backdrop and setting. The editing is smooth specially in the closing shots when the white van drives away, taking Indrajit Ganguly back to the world he belongs – the film world in Bengal.

All in all, Jyeshthoputro is a fine effort by Kaushik Ganguly aided by by some brilliant performances. Go for it.

Bengali, Drama, Color