Aditya Dhar’s sophomore feature, Dhurandhar, is an eight-chapter espionage thriller that establishes itself immediately as a high-octane, hyper-stylised drama. But as the story progresses, there is a growing sense that the makers are sprinting toward a finale without the creative oxygen needed to sustain the grand design it so confidently sketches.

The film roots its narrative in the wounds left by two seismic failures of Indian intelligence – the hijacking of the Air India flight to Kandahar in 1999 and the attack on the Indian Parliament in 2001. In the wake of these national ruptures, Intelligence Bureau chief Ajay Sanyal (R Madhavan) devises a covert counteroffensive. He comes up with an audacious plan to infiltrate the tangled ecosystem of terror networks, underworld syndicates, and the ISI’s shadow operations across Pakistan. The operation’s unlikely fulcrum is a young recruit dispatched under the alias Hamza Ali Mazari (Ranveer Singh) to Lyari, Karachi’s labyrinthine stronghold of gangs and political patronage. Mazari gradually threads his way into the orbit of Rehman Dakait (Akshaye Khanna), the area’s notorious gangster-philosopher king, and begins the arduous process of carrying out his covert mission.

Dhurandhar opens with an image designed to compress a decade of national anxiety into a single frame. Sanyal standing before the hijacked Indian Airlines flight, his face carrying the strain of the unprepared attack. So, from the outset, the film signals its intention to immerse us in a world where bureaucracy, geopolitics, and subterranean violence bleed into one another. Sanyal’s efforts to launch the covert mission are depicted as a near-operatic struggle against inertia and institutional resistance. When Hamza finally arrives in Lyari, these passages offer a brisk but telling glimpse into the uneasy alliances that underpin the region. Local strongmen, ministers, and Pakistan’s intelligence apparatus function in a quietly symbiotic arrangement when it comes to orchestrating mayhem across India.

The film also sketches the political stakes of Lyari itself, a constituency whose electoral weight grants access to the country’s larger corridors of power. Dhar gestures toward the internal fractures of Pakistan as well. The conflict with Balochistan surfaces in the contempt of SP Chaudhary Aslam ( Sanjay Dutt), whose disdain for the Baloch is fueled by a history of betrayal. The film’s most striking sequence arrives when Pakistani terrorist orchestrators gather around a television set to watch the 26/11 attack unfold in real time, while Hamza is forced to be present with them. As the screen floods with red, the film cuts to stark title cards replaying the actual intercepted conversations between the terrorists and their handlers. It’s an audacious and disorienting decision from a filmmaker – one that suddenly anchors the fictional narrative in the documented horror of a national trauma. For just that moment, Dhurandhar transcends its genre obligations and confronts the audience with something bracingly direct.

As the film unfolds in a macho, unforgiving world dominated almost entirely by men, it is unsurprising that the women are left with little agency. The romance between Hamza and Yalina (Sara Arjun) receives so little narrative scaffolding that their sudden segue into the song ‘Gehra Hua‘ feels more like acontractual obligation. It also marks the beginning of the film’s downward slide. Hamza’s mission, initially the film’s moral and narrative engine, drifts into the background as he becomes increasingly preoccupied with safeguarding Rehman and his ambitions. Even the interval’s manufactured suspense, meant to jolt the plot, highlights the film’s eroding sense of purpose.

The production’s frequent jaunts to exotic locations may offer a visual flourish, but by the time the action shifts to a forested terrain for its showdown, the spell has broken. The setting, stripped of mood or menace, lacks the atmospheric charge the film once promised. A chase sequence staged to impress a girl, as well as a covertly recorded phone-camera conversation meant to resemble a clandestine operation, feel jarringly out of place. The early stretches of gore and violence, ushering the viewer into the film’s tense, hyper-vigilant milieu, eventually slip into excess, and by the time it arrives at its climactic stretch, a certain messiness has already set in. Scenes pile up rather than build, and the film begins to feel weighed down by its abundance of footage. The final minutes confirm the film’s sequel (on March 19, 2026), announced with a confidence that feels more strategic than organic.

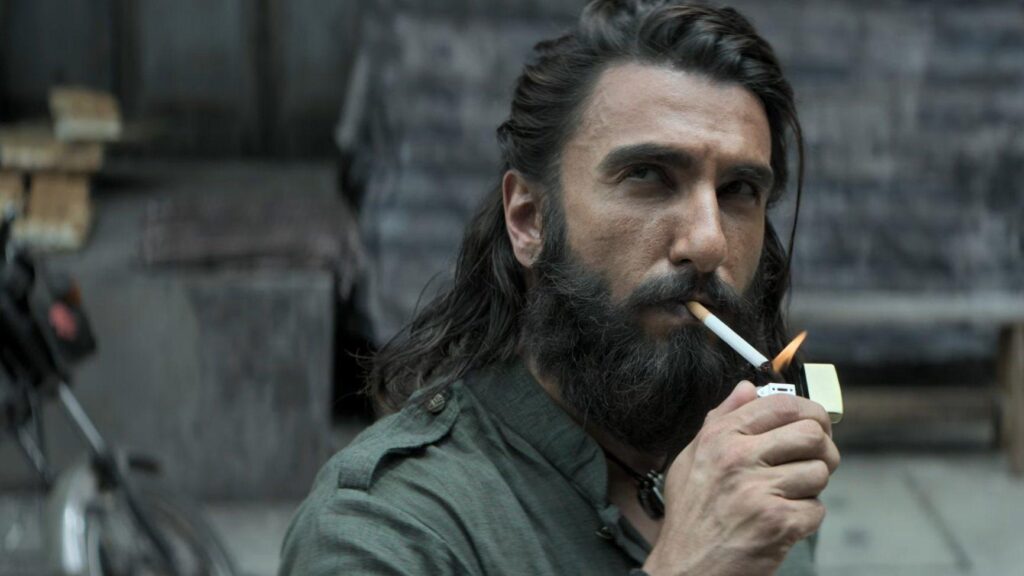

Ranveer Singh cuts an imposing figure, though his menacing presence carries a faint, knowing echo of his Alauddin Khilji from Padmaavat. There is a coiled silliness to him as well, an unpredictability that works in the film’s favour, and he shoulders much of the narrative’s weight with conviction. Akshaye Khanna brings a sly, almost feline charm to the role, stealing many a scene. Sanjay Dutt effectively portrays the grizzled, morally ambiguous police officer sketched in shades of grey. He is ruthless, unrelenting, and willing to go to any length to corner Rehman. Curiously, he is credited as a ‘special appearance’, given that he occupies more screen time, and certainly more narrative space, than R Madhavan. Arjun Rampal adds another layer of menace to the ensemble while Rakesh Bedi lends unexpected texture to the film with a performance that beautifully blends comic relief with cold-blooded pragmatism. Sara Arjun brings a brief flicker of charm to the scenes she inhabits, but, sadly for her, is saddled with a predictable saviour arc and little more.

Vikash Nowlakha’s cinematography captures the film’s world with a finesse that is both atmospheric and psychologically attentive. He frames the characters not only within the dense, constricted interiors of their lives but also against the vast, arid mountainous stretches of the region, giving the film a sense of scale that often exceeds its narrative reach. Shivkumar V Panicker’s editing gives the action sequences their sharp, muscular momentum, while allowing quieter moments the space to breathe. His intercutting of archival footage with staged events adds a brief, bracing immediacy to the film’s otherwise stylised world. Bishwadeep Chatterjee’s sound design draws us into the film’s shifting emotional temperatures. Whilee large-scale set pieces are rendered with immersive precision, the silences carry an equal, sometimes heavier, weight. Shashwat Sachdev’s background score, thankfully, resists the temptation to overwhelm.

Dhurandhar wants to be the beginning of something larger. What it truly needs, though, is the discipline to stand firmly on its own. Here, the promise of ‘more to come’ arrives less like an expansion and more like a distraction toward future chapters before the present one has even fully earned our trust.

Hindi, Action, Drama, Color