During my adolescence in the 1960s, by sheer happenstance I became privy to the insulated world of a Bombay kotha: It wasn’t as glitzy or hyper-fantasticated, of course, as Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s depiction in Heermandi: The Diamond Bazaar, set in Lahore of the 1940s. Yet, it had all of Heeramandi‘s essential elements – drop-dead beautiful women, the internecine rivalry between them, a despotic chaudhran and the next suzerain, a kotha’s madame as wily as wise and who ruled the most patronised establishment. And then there was the transgender who would be an inveterate gossip and served as an informant of the goings-on at the other ‘houses of ill-fame’ as they were called.

This rarefied world derived its name from the adjoining Kennedy Bridge (aka Pawan Pull for the breeze wafting from the railway tracks under the bridge). The kotha, thus called Kennedy Bridge, was separated from a compound of rabbit-hole-like rooms where the lesser skillful tawaifs or courtesans were lodged till they were well-versed in ‘tameez’ and ‘tehzeeb’ (manners and culture), as well as the mandatory coquettish ‘adas’ (a mixture of grace, beauty and elegance, coquetry and charm) required of a infallibly seductive courtesan. People would line up on the bridge to watch the spectacle for gratis from close to midnight to the break of dawn. Ironically, the Congress House branch office was just a pebble’s throw away.

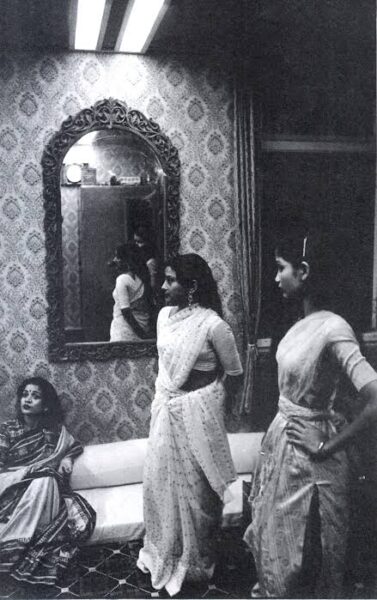

Inside the kothas, expressionless musicians at the harmonium, dholaks, sarangis and tablas would perform in tandem for a monthly wage with the tawaifs chosen to dance for the evening – a hybrid form of Kathak and film set-pieces. Wads of notes would be showered upon them, plus the hand-maidens served paan in carved silver thalis in return for which a nazrana of gold coins or high denomination currency notes would be placed as tips. These would be handed over to the madame. A majority of tawaifs were acquired from an agent who would buy children before they had attained puberty from diverse cities ranging from Agra and villages in north India, Nepal and more. Former royalty, Nawabs from Hyderabad, wealthy business lords and occasionally film personalities would fetch up for the jashn-e-mehfils in chauffeur driven stretch cars or tightly shuttered horse carriages at this kotha. Lore goes that on occasion Raj Kapoor and Nargis would suddenly appear to partake of the mehfils – a rambunctious concatenation of mujras.

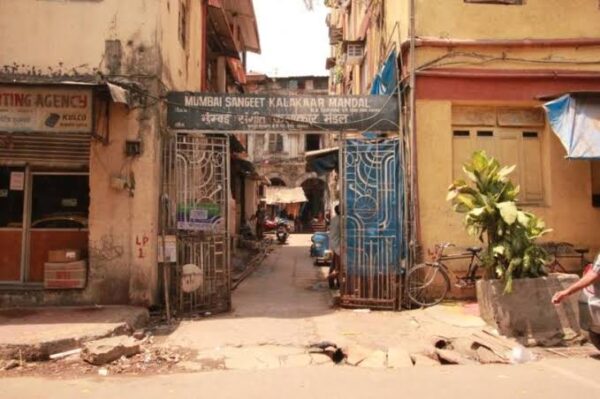

So, how did I gain free access to the Kennedy Bridge kotha and compound (outside which a fading sign still spelt out Mumbai Sageet Kalaakar Mandal)? I must have been eight or nine years old and would be taken after school hours to a playground close by. Saiba, our chauffeur would leave me there, and would promise that he would return in an hour. He had a secret amour, a sex-worker banished from the kotha since she was no longer young or a proficient dancer.

One evening, weary of the playground since Saiba hadn’t shown up for over an hour, I tried to cross over to the compound. A large car had speeded by just then, and I was saved from a near-fatal accident by a star inmate of the kotha. Her name was Shehezadi. She was childless (the repercussions of a botched-up abortion) and almost immediately regarded me as her surrogate child and would secretly smuggle me into her chamber, an ornate one with a carved walnut bed, velvet curtains and a life-sized portrait of Radha-Krishna, besides the usual ugaldans, paandans and a peacock feather fans. In the main hall, the durbar as it were, tall slanted framed, ornamental mirrors, were hung on the four corners of the room. A profusion of brass vases with roses scented the air.

This continued for a couple of years. I developed a crush on Shehezadi, my saviour till she vanished into thin air. She would give me random presents: a water-pistol, golden paper crowns and expensive pens. For her generosity I would call her ‘Kuchh Kuchh’ (something or the other). Then, a bolt out of the blue: the other tawaifs, who had begun to dote on me, said sadly that Shehezadi had eloped with her besotted ‘seth saab’, a young scion of a business family. They had probably run away to Dehradun, where the ‘seth saab’ possessed a farmhouse. “She’s fortunate to find freedom,” I was consoled but felt betrayed since I had dreamt of making Shehezadi, my own bride some day. Childish, yes, immature, yes. But I could admit my secret to Saiba, who was in terror that I may reveal his furtive trysts in the compound, to the elders.

I didn’t but after decades in my 50s, staged a theatre play titled Kennedy Bridge, a musical, at the NCPA, using the mixed media of theatre, video, and set backdrops by prominent contemporary artists, including MF Husain and Akbar Padamsee, and background music riffs by AR Rahman. The acting cast was led by the then upcoming Richa Chadha, Manav Gohil and Achint Kaur. The production didn’t click. The late erudite critic, Anil Dharker, described it as ‘Bollywood rubbish’. So be it.

This preamble is by way of understanding (more for myself than anyone else) my response to Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Heeramandi, a fictional work based on a concept by Moin Beg, located in the Lahore of the incipient freedom struggle of the 1940s. I could instantly identify with Bhansali’s kotha, as filigreed and design heavy the props may have been (the Pakeezah (1972) influence is evident). There were some flaws, too: most tawaifs generally abhor liquor in keeping with their religion (at times because of conversion to Islam), resorting rather to opium and intoxicating khimam (liquid tobacco) lathered on paan beedas. Moreover, in Heeramandi an elaborate Eid sequence jars, since it isn’t preceded by any signs of fasting during the Ramzan month, which is dutifully observed in the traditional kothas. At least, the sighting of the crescent moon, on the eve of the Ramzan celebrations could have been incorporated. Carelessly, an Urdu newspaper is shown with headlines about this millennium’s Covid pandemic while a relatively modern novel sticks out like a sore thumb at a bookshop shelf. As for the grafting of the elongated sub-plot about the Quit India Movement, it is awkwardly directed in comparison to the chess-like games being played by a phalanx of all the varied women of spine in the kothas.

Indeed, Bhansali’s no-holds-excluded endeavour is at its most insightful and redolent of powerful dramaturgy when the camera moves voyeuristically into the intrigues within the portals of the Heeramandi bazaar. A war of deceit and murderous strategies between the women behind the becurtained kothas is on. From my Kennedy Bridge experience (however, brief it may have been), the web series struck me not only as plausible but imperative to break the mould of the ‘vestal virgin naachnewaali’, advanced so far by our cinema on similar themes, be it Kamal Amrohi’s Pakeezah or K Asif’s Mughal-e-Azam (1960). If the prince and the courtesan Anarkali had a sexual relationship in the latter, it was only implied, albeit poetically. In fact, Mughal-e-Azam and Pakeezah unarguably still stand out as masterpieces. However, that doesn’t mean Heeramandi is ‘rubbish’, ‘overbloated’ or a ‘valuable waste of time and resources’, as lambasted by several detractors. I can only say that I viewed the eight-hour-plus web series on Netflix, from a personally experiential point of view.

The bazaar’s chaudhran (Anju Mahindroo), depicted in quicker than finger-snap scenes, is established as the final decision-maker, even if it is tokenism. The Kennedy Bridge’s kotha had a similar Neelam Chaudhran, consulted yes but never obeyed. Here, a benign but fearsome woman, Allarakhi, followed her own diktats which led to the consolidation of her own clout, and as Bhansali interpreted it, to unspeakable tragedy. Either way, in sum, the judgments in the series culminate in the solidarity of the Heeramandi women to bury their hatchet and defy the British Führers with a mashaal-brandishing march towards the colonial stronghold. Historical inaccuracies apart, this coming together of the age-old ‘nautch girls’ resonates, given the current unilateral conditions of today. Women won’t take subjugation anymore, is the significant takeaway from Heeramandi. In addition the polemics between the group of the women in Heeramandi vivify polarized elements: viciousness with kind-heartedness, triumph with tragedy, resilience with impatience, revenge with withdrawal, death with birth, youthfulness with the setting in of old age, and most significantly, subjugation with insurrection. Here are characters suffused with mental aberrations and simultaneously, a native intelligence.

Circa 1983, Ismail Merchant had helmed a docu-drama The Courtesans Of Bombay, picturized in the compound of Kennedy Bridge kotha. However, with some additional, scripted scenes featuring Zohra Sehgal and Saeed Jaffrey, it was a disappointing hotchpotch.

I’m no Bhansali bhakt. His debut film Khamoshi: The Musical (1996) continues to stand out at his career-best. To me, his version on Devdas (2002) was a downer, since elements of pretentiousness and hysterical melodrama had seeped in. Black (2005), Saawariya (2007) and Guzaarish (2010) were derivative of foreign sources (rom Arthur Penn’s The Miracle Worker(1962), Luchino Visconti’s White Nights (1957) based on a novel by Dostoevsky, and The Sea Inside (2004) from Alejandro Amenabar’s Spanish film culled from a true story of a sailor who becomes a quadriplegic after an accident respectively). Goliyon Ki Raasleela Ram-Leela (2013), Bajirao Mastani (2015) and Padmavaat (2018) were all bombast with no depth whatsoever and at most, helped to establish the Ranveer Singh-Deepika Padukone screen pair.

As for Gangubai Kathiawadi (2022), in retrospect, it appears to be a prep for the Heeramandi opus. Alia Bhatt may have pulled off the act of a much older woman convincingly and with ingrained professionalism but no way came close to Manisha Koirala’s engaging and magnificent enactment of an ageing, frequently merciless Mallikajaan, the frontline kotha’s queen bee. She is in a word, outstanding. It is tempting to imagine Rekha in the same role, though it would have been a more than predictable choice.

Of the others, Richa Chadha’s rendition of the jilted tawaif, Lajjo, is as multi-layered as it was deeply tragic. Incidentally, her Kathak dance performance stands out among the rest of the dance interludes which are either abbreviated perhaps because they are cavalierly choreographed, especially surprising in the case of Aditi Rao Hydari, trained in Kathak. Additionally, her characterisation of a do-good kothewaali is underscored beyond endurance. Sharmin Segal, as the poetry spouting tawaif, who refuses to auction her ‘nath’ (virginity), strangely strikes a one-note performance, appearing beatific as if she has gatecrashed into the wrong mehfil. Sonakshi Sinha, in a dual role, demonstrates her untapped talent: hard as nails and unapologetically vindictive. Farida Jalal as Qudsia Begum, the aristocratic, empathetic grandma is flawless, a portrayal that is as warm-hearted as it is believable in conveying that pride is one thing, prejudice another.

Unwaveringly, hard work has gone into the production design, set décor and cinematography which cannot be indifferently dismissed as ostentatious. In the technical sphere, the editing was slack but then the tempo and concision is the director’s prerogative. Errors apart, of all the contemporary directors, Bhansali possesses a distinctive craftsmanship, has taken on the onus of creating his own music scores and is today a market force allocated hugely lavish resources, a rarity in these times of assigning meagre budgets. And of late, deep pockets have prioritised male-centric, violence for violence sake’s yuckfests. For Netflix to back Heeramandi with a dream budget, indicates that what Bhansali wants, Bhansali gets, one of the scarce few graduates from the Film & Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune, to do so. Rajkumar Hirani and Vidhu Vinod Chopra are the other two notables.

Frankly, you may loathe or relate to Heeramandi. My take is coloured by the fact that I have experienced a bazaar in myriad ways close to the one set in Lahore. Meanwhile, on our shores the bazaars everywhere from Lucknow and Hyderabad to Mumbai and Delhi have gone, initially with the onset of beer parlours, then escort services and now dating apps on the Internet. To approach a subject set in a bygone era and the focus being on Muslim women – a theme that’s been by large canned in the new millennium – I would applaud the recreation of the 1940s beleaguered world (the setting could well have been Lucknow). Truly, never mind the nicks in the jewels.

Photographs courtesy Khalid Mohammed.