Like most people, my cinematic journey of filmmaker Satyajit Ray began with the first of his now immortal Apu trilogy, Pather Panchali (1955). I first happened to watch the film when I was around 13 years at the Maratha Mandir theatre in Bombay, now Mumbai, with a young production assistant from RK Studios who wanted to watch this film everyone was talking about and which was winning awards left, right and centre. The theatre was almost empty. “That Ray is so tall,” is all he seemed to know to describe Ray. He was a nice guy – I do not recall his name – but he went to sleep as soon as the film began and woke up just a few minutes before it ended. “It’s. boring film. How come it has won so many awards?” he yawned as we walked out. He saw me to the bus stop that would take me to Shivaji Park as he had promised my mother. I did not understand the film either and wondered why everyone was falling all over it. My parents, huge cine-buffs, were disappointed with my cold response to Pather Panchali. Nevertheless some scenes touched a deep chord in me – the huge, moving shadow on the wall of the doddering old Indir Thakrun narrating a scary but very familiar fairy tale to the two kids Apu and Durga; Sarbajaya’s cruel treatment of Indir Thakrun; and three, the rolling down of her dented vessel down the rocks and into the pond, sending ripples around it after Apu and Durga discover that she is dead.

I had not read the original novel Pather Panchali on which the film was based till then. When my mother remembered this, she brought me a smaller edition for children called Aam Aantir Bhenpu with a beautiful cover designed by Ray. I practically gulped it down over three or four days, shrugging off Maa’s scoldings for habitually avoiding homework. I have rewatched Pather Panchali many times over the years, each time carrying away with me a different reading of the film and each time discovering something new in the film. I understood one thing about Ray as a filmmaker – he had the rare ability to transcend the limits of literature while turning a novel into a film. His way of creating dialogue was just like we spoke in our normal lives – nothing decorative, not pedantic, not arrogant or even dramatic in any way. As for rest of the trilogy, I watched Aparajito (1956) much after it was released. I had exams but I watched it later. The scenes that stuck in my teenage mind then were – a growing Apu trying to explain to his mother the revolution of the earth around the sun with a fruit or two, and I felt very very sad when I saw Sarbajaya waiting under a tree for her son away in the city who had assured he that he would be back but he does not. We do not see her dying but the tree under which she waited, leaning against its trunk, stands without the woman seated beneath but the air filled with the sound of crickets and the flickering of the fireflies. I will never forget this microcosm of the universality of a mother’s pain when she realises that her son has moved away from her. After watching Apur Sansar (1959), all I carried away from the film was a giant crush on its handsome debutant hero, Soumitra Chatterjee, who, a malicious friend from Calcutta pointed out, was recently married to his lady love. Many years later, I met him many times and built up a sort of warm acquaintance and learnt a lot about his memories of the director who discovered him.

When Kanchenjungha (1962) released at Lotus Cinema in Mumbai for all shows in the day, I had just joined college and was already an admirer of Ray. Why, I cannot pinpoint out except that his films were so moving that you carried them out of the theatre with you. I watched the film for three shows over three days in two weeks and my parents did not complain probably because they liked the fact that I was developing a taste for good cinema. Kanchenjungha, like Kamal Amrohi’s Mahal (1949), which I saw many years after it was released, kept haunting me for weeks together. It was the cinematography and the editing in both these films that held me captive though I had no idea about these techniques and their use in cinema. The very low-key treatment of the relationships, the slightly Marxist slant my Marxist father pointed out to me through the silent interchange between the feudal old Calcutta honcho (Chhabi Biswas) as he looks down on the little Nepali urchin savouring a whole Cadbury’s chocolate, which angers the older man, proud about his affluence, and his power.

From this point on, I began to realise a hunger within me to meet Ray in person. I went hunting for his postal address. I have no memory of how I finally managed to get it. I do recall before that, Mahanagar (1963) had released in Lotus and totally taken in by it, I wrote down my own analysis of the film – a very raw one when I look back at it now, But then I wanted to send it to Ray himself. The theatre drew a full house, surprising for a Bombay audience to a Ray film. I hesitantly took out my pen – a fountain pen in those days – and penned a letter to him. I do not have a copy of it but I analysed Mahanagar briefly focussing on the points that appealed to me. I also asked him why he was not making a film on Pagla Dashu, a book for children authored by his late father Sukumar Roy. Pagla Dashu is the hero of a series of stories revolving round his antics. He is a very funny boy on the surface but the undercurrent shows he is very diabolic in his mischief and naughtiness. The small stories of his adventures are confined to the school he attends and there are different kinds of digs to poke the teachers and the education system per se.

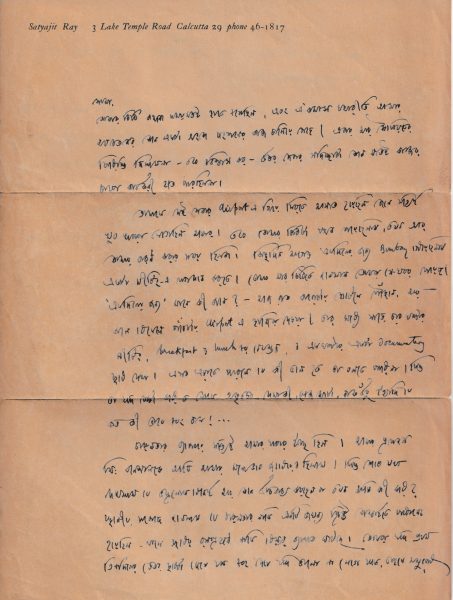

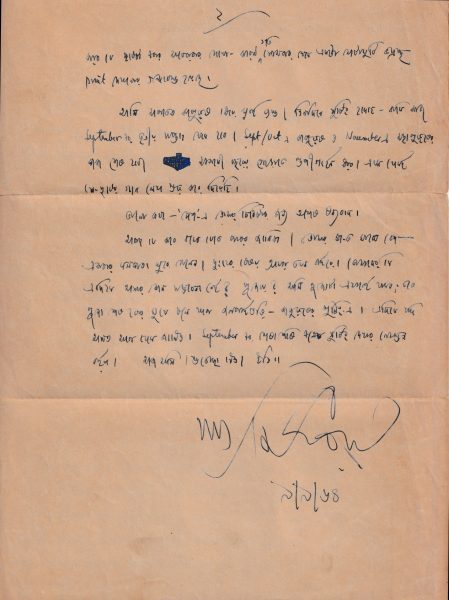

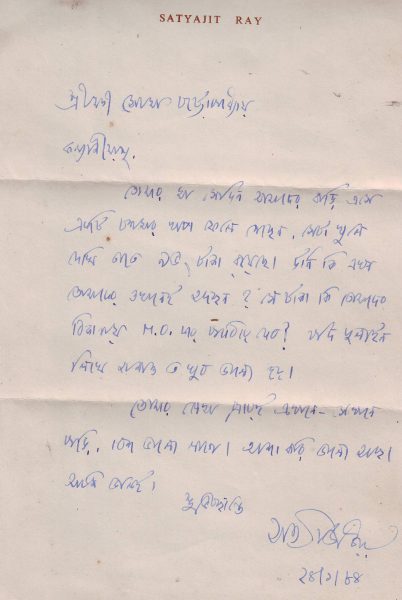

A few weeks later, he sent a reply in an envelope with my name and address written in his unique hand. Maa and I were pleasantly shocked. The two-page letter was written in pen by him. His son said that he always made it a point to answer every single letter he received and even wrote the address on the envelope in his own hand. His letter said that he did not remember having received my letter but found it later. He said that he shared with me, our Economics background which he dropped out of from Presidency College mid-way. “I think a man’s true education begins after he steps out of his institution. I read much more than I read when I was a student,” he wrote. “I have met your parents already. Why have I not met you yet? Perhaps, we will meet the next time,” he wrote.

He also said that he had just finished his work on Nastaneer and lamented that the producer had insisted on changing the name of the film to Charulata. “Thankfully, they did not ask to make any changes in the story,” he said, adding that it was not possible to picturise Pagla Dashu because the potshots taken at the education system would not go down well with the powers-that-be. He expressed his plan on making a documentary on the danseuse Bala Saraswati. “I had gone to watch her recital in Calcutta recently and was stunned with the excellence in performing. I went to the dressing room to meet her after the performance to tell her that I wanted to make a documentary on her. She said, “I am so ugly, why do you want to make a film on me?”

The family then lived on 3, Lake Temple Road, which I had visited once and the family had welcomed me quite warmly. Babu, or Sandip was about ten years old then. His father showed me his kheror khata – the famous scripts he wrote in his own hand in a notebook bound with a red cloth like grocer’s account books. It was filled with his sketches of the characters, the costumes he had planned they would wear, and small rectangular frames within each page to illustrate his conception of how he would frame each scene! I was too raw to understand all the technicality but his close attention to the slightest of details was amazing. I hardly looked at the written script, so mesmerised I was with the sketches including even the footwear the characters would be wearing. Many years later, while writing my book on Aparna Sen’s films, she had given me all her original scripts to study and except for the sketches, I could clearly see the deep influence of Ray in her directorial work which reflected in her films.

One anecdote I would love to narrate here. When I got married in 1965 and shifted to Kolkata, my in-laws would poke me for being a ‘film journalist’ which, in those years, was looked down upon as very low in the hierarchy of journalism. My brother-in-law, then 19, challenged me to call up Ray in front of him. I did, with by heart beating fast in case I failed. He took the call himself We had a short conversation, which eft me thrilled and my brother-in-law was stunned!

Soon after this, I began writing a very long history on Bengali cinema for a competition announced by Calcutta University. I got stuck in my research and called Ray up for help. He said the book Indian Film, jointly authored by Erik Barnouw and S Krishnaswamy, would be a very good frame of reference adding that it was out of print. “If you want to borrow my copy, you can pick it up from my house and give it back to me after your work is over.” Off I went to his home now at 1/1A Bishop Lefroy Road where he lived till he passed away. He sat me down in the lounge, smiled and brought out the book. I touched it as if it was the Bhagwadgita, felt it and after some small talk, I left. Of course, I gave back the book after my work was over but the results of the competition remained an unfinished history. To be honest, I did not feel like giving it back but I was word-bound to him. The book is a bible, particularly for early Indian cinema history. Many years later, I noticed the same book stocked in the library of a journalism school in Bombay I taught in. I confess I flicked the book and no one knew and still hold it as one of my precious possessions in my film library.

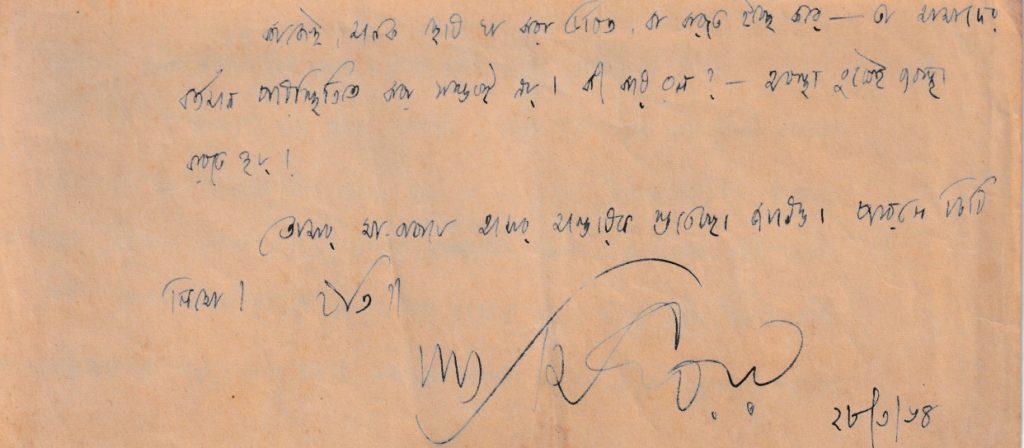

We exchanged four letters in all making eight altogether. Sadly, I have misplaced one of them over the years. The last letter is dated sometime in 1984 in which he informed me that my mother had left behind her spectacle case which carried some cash inside. He asked me if he could send it by Money Order and I wrote a short response saying yes. The Money Order soon arrived at my mother’s place in due course.

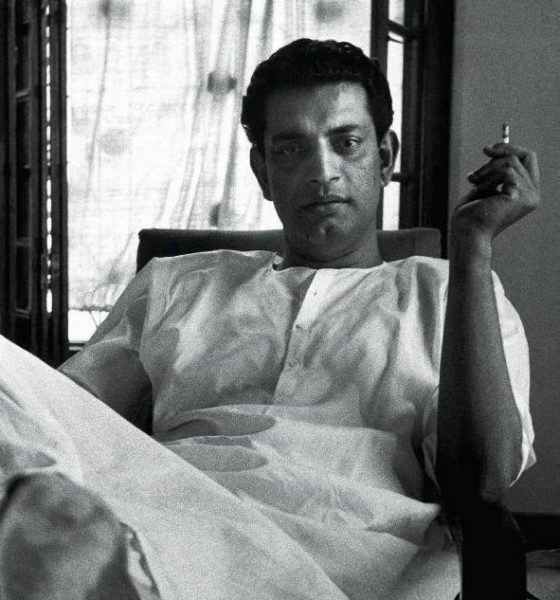

I once tried to see him once in his Bishop Lefroy Road residence when he was quite sick. By then, the then-Ruling Marxist Government had constructed an elevator that opened right outside his entrance on the second floor. But the security guard did not let me in saying, “visitors are not allowed.” Looking back, I feel it was good because I would not want to remember that 6’ 4” tall, dark and handsome man with that bass voice, now a ghost of his former self, relaxing in his study, minus his cigarette or, later replaced with a piple. It is good to fall back on the good memories of a man who lived life and cinema on his own terms, setting out some invisible rules for small people like me to follow or at least try.

PS: A very young friend of mine, Arindam Saha Sardar, has created a digital archive of original letters written by great celebrities from different fields in his suburban home. I have gifted the letters to this archive and he is taking very good care of them.