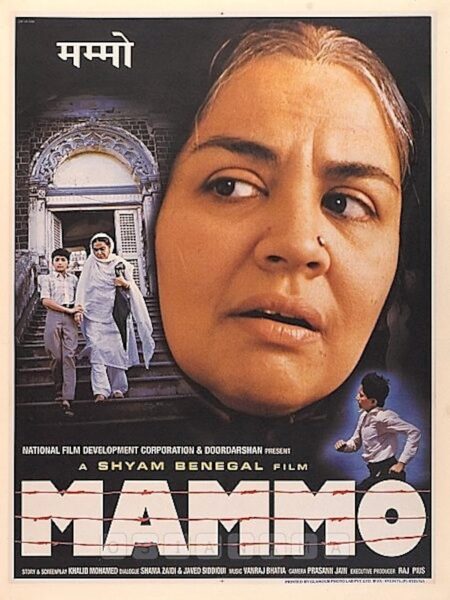

Khalid Mohamed recalls how he wrote the real-life story and screenplay of the National Award-winning film, Mammo (1994), now accessible on YouTube and streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

A decade, two decades, quarter of a century, half a century, these all become momentous for an event one cherishes. Personally and privately. But the fact had completely passed by my memory (it’s thinning with age, I guess), that 30 years have elapsed since Mammo‘s scripting. This may be a big deal for me, not for others. So, I am more than surprised when half-a-dozen inbox messages on my Facebook page, remind me every year that so many years have whizzed by since Mammo. One message asked, “How do you feel?” which was kind, but so like those TV interviewers who shove a mic into faces to quiz, “Aapke Is Vishay Pe Yya Feelings Hain?” The answer’s usually,“I am very happy, thank you” or a sprint-off looking as if I had been stabbed with a dagger in the heart.

How do I feel? Elation for sure, since the film is remembered. It’s accessible on YouTube and is on Prime Amazon Video. There’s this boundless gratitude for sure to Shyam Benegal who guided me through the jagged path towards story and script writing. And for sure, a certain sense of self-satisfaction. That first active involvement in film-making allowed me to multi-task, however intermittent that may have been. Journalism was and is my first calling, films an opportunity to travel to another zone – to narrate stories which merit worth sharing. Or at least, I hope they do.

My childhood, ipso facto, brought me close to women of fortitude whose stories continue to swirl restlessly within me. Quite unfathomably, I am often told to grow out of myself, escape from the ‘prison’ of my own memories. Prison? Hardly. I believe I’m in possession of a treasure trove, a priceless legacy. A truly insensitive remark, however, was made by a reviewer that I was encashing on my nostalgia. That hurt. Can one ever really encash on one’s family and its vicissitudes? Rather than encashment, I would say summoning up the stories has served as a very small payback for the women of my fractured family.

I’d written a toss-away, 600-word column in The Times Of India’s Sunday edition about my grandmother’s elder sister — my grand-aunt Mehmooda Begum —who lived in post-partition Multan. It had caught the attention of Shyam Sir. The column was about an aged woman, who could no longer go back to Pakistan, after visiting us on a tourist visa. Mehmooda Begum, whom we fondly called Mammo, was penniless, homeless. Her relatives in Pakistan considered her a burden, an unwanted presence and an extra mouth to feed. Widowed, Mammo had returned to Mumbai to be with her sister, Fayazi. And Fayazi’s grandson, me. In her late 60s, she didn’t have a roof above her head in Multan anymore. Would we take her in? Somehow or the other, could we keep her with us forever? She promised to cook, clean, teach the Quran to the neighbourhood kids, to pay for her upkeep. We couldn’t afford to, I was still in school. My grandfather had passed away and till a probate was passed on his will, we could just about manage to make ends meet, thanks to kind Parsi neighbours.

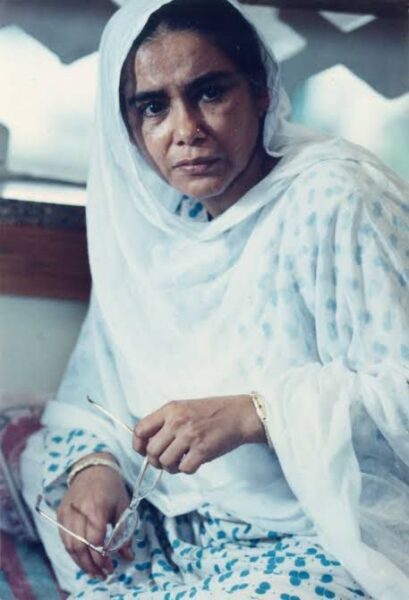

There are many women, across the border, like Mammo. Shyam Sir felt the story had something valid to say. Writer Javed Sidiqui said, “A country was divided. Not its people, were they?” After a year or more of re-drafts, the NFDC-funded Mammo was shot on a piffling budget largely on location in a brand-new Jogeshwari housing colony. Not a wise decision, as Shyam Sir was to point out later. He uses sync sound, avoids post-production dubbing. And manic construction work was on in the vicinity, the unit had to work during the rare quiet hours when the workers were catching a shut-eye, and on Sundays. Yet, Shyam Sir soldiered on, even taking over as the operating cinematographer occasionally. A long take of Mammo, Fayazi and the boy walking on a windy monsoon morning across the Haji Ali pathway, was handled by him. That one shot encapsulated the real-life uncertainty, a stasis in our lives we had undergone when Mammo had intruded into our home. Yes intrusion. As a brattish adolescent, I objected to sharing my small home, aggravated by her ceaseless chatter. Slowly but surely, she changed that. I became Fan No. 1 of Mammo Nani (maternal grandmother), as resilient as Mumbai city.

Who was to know what would happen to Mammo tomorrow? Our worst fears came true. She was deported, she wasn’t permitted five minutes to pack her clothes in a tin sandook. She was dumped into the police-manned Frontier Mail chugging towards a darkness of no return. There was no news from her, after that, we weren’t sure where she was, how she was. If she was. Providentially,the unbeatable Mammo was back some ten years later, carrying a death certificate. This death certificate ruse actually happened just a week before the film was being wrapped up. There! By some divinity or just by my Mammo nani’s sleight of mind – which wasn’t unlike Tom Sawyer’s – she was in our home, a dead woman laughing. Her laughter was unlike anything imaginable, a cross between a joyous cackle and a motorised giggle. You’d have loved her if you ever met her. Guaranteed. The first thing she did with strangers, was to cup their cheeks affectionately and say, “Child, let me make you a glass of Roohafza. It’s horribly hot outside, you must be thirsty.”

Before the shoot kicked off, Shyam sir had dropped in at our apartment to meet Mammo and Fayazi Nanis. They were shy and wandered off into another room. He picked up little details of the décor (or the lack thereof) in the house and incorporated them – like a table topped with sharbat bottles and fruit, a rattly fridge and gauzy curtains. The kind of clothes they wore were replicated by Shyam Sir’s daughter and costume designer, Pia Benegal.

My closest friends from the film society circuit and from college then, oddly gave me no support or a thumbs up for Mammo, my first and auspicious breakaway from journalism. Actually, they haven’t for any of my films perhaps because they didn’t meet ‘film society standards’. All that one of my closest friends could say after the Mammo screening, is, “My God, she’s back in India. Won’t the authorities track her down and deport her all over again?” I had discussed this with Shyam Sir, he had assured me nothing of the sort would happen. Mammo no longer had an identity. Yet, whenever an unexpected doorbell rang, I’d be anxious. Gratifyingly, Mammo stayed on, and her true story could be told till its true-to-life conclusion

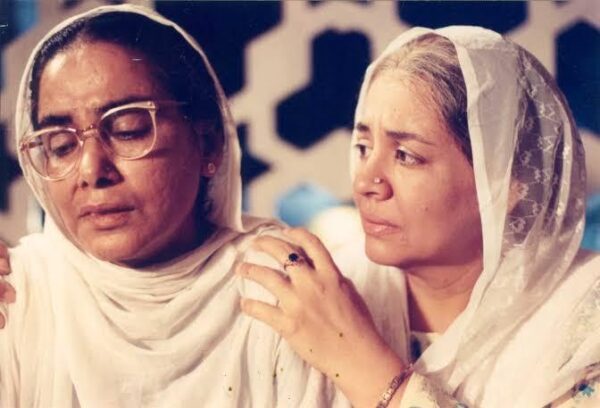

The script was actually written with Waheeda Rehman in mind for the title role. We had flown to Bengalaru to meet her at her farmhouse on the outskirts of the city. She heard the story of Mammo out, but we returned with a rejection slip. Unsure, she felt the subject was controversial. Why portray a Pakistani woman? So be it. Waheeda Rehman, was in fact, Shyam Sir’s first choice for Ankur, too, but she had declined.Shyam sir felt the reason for that was his lack of credentials, then, as a filmmaker. “I was a first-timer, so Waheeda Rehman didn’t agree to do Ankur.” Neither hasd his other Ankur choices Anju Mahendroo, Sharada and Aparna Sen. Subsequently, Shyam sir and Waheeda Rehman did work together for one of his TV serials. Fortuitously, Shyam Sir then cast Farida Jalal as Mammo and Surekha Sikri as Fayazi.

Farida Jalal was letter-perfect as Mammo. Shyam Sir called Surekha Sikri over from Delhi where she was a formidable name in theatre. For the character of their grandson, he selected Amit Phalke, descended from the Dadasaheb Phalke family. Farida Jalal’s Urdu diction was spot-on and her bonhomie warmer than Pashmina. Surekha Sikri’s blend of sorrow with happiness was absolutely in sync with the real-life Fayazi. Aditya Chopra contacted her to play the grandmother’s part in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge but she nixed it because she was being paid next to nothing. The Yashraj banner never contacted her again.

The theme song of Mammo, Yeh Faasle Teri Galiyon Ke, sung by Jagjit Singh, almost didn’t happen. Shyam Sir’s lyricist hadn’t delivered on time. I requested him to get in touch with Gulzar, who wrote the song overnight.

When the film opened the International Film Festival of India, held in Mumbai that year, strangely neither Mammo nor Fayazi Nani showed any interest whatsover. They were more thrilled by the photograph I showed them, of me on the festival dais with Shyam Sir along with the cast and crew. “I just hope you haven’t made us out to be nut cases,” Fayazi Nani had commented. Mammo had let off one of her musical cackles. A month later, I got a video print, insisting that they had to see how they’d been portrayed. Again, no interest. Fayazi Nani fell asleep after 10 minutes, Mammo Nani survived half an hour. Major addicts of Bollywood blockbusters both, they just could not whip up enthusiasm for a “hungry” looking film – meaning with no ornate production values. Besides those were the days of the Amitabh Bachchan Raj. They’d see the video cassette of the opulently mounted Khuda Gawah (1992) repeatedly, squealing with delight, “He looks so good in a turban and cloak”, worn for his bridal night scene with Sridevi. Plus, Mammo nani would be delighted whenever the song “I’m very very sorry”, featuring Sridevi and Salman Khan popped up TV. “Ha ha! I’m very very sorry,” she’d trill before strolling off to the verandah for an afternoon nap.

Mammo won two National Awards, the Best Hindi Film and Best Supporting Actress for Surekha Sikri. Farida Jalal carried home the Filmfare trophy, the Critics’ choice for Best Actress, as well as the Bengal film Journalists’ Association (BFJA) for Best Actress (Hindi). When I filled in Mammo and Fayazi about the awards, they nodded, “Good. As long as you’re happy.” I suspect they didn’t relish the idea of our private lives being transcribed to screen. Some of our family’s relatives were livid: there was a bit about a sizeable sum of money borrowed from my grandmum, but never returned during our years of need. They were quite upset by the mention of their real names, particularly Aunt Anwari and Uncle Jabbar who’d wronged the two old ladies, demanding favours. Never returning any.

Around 1998, Fayazi and Mammo passed away within two months of each other. Fayazi Nani had slipped while feeding pigeons in our building’s corridor on a rainy day. Mammo fell in the kitchen while cooking herself an omelette for sehri. Despite her advancing age, she’d observe the roza fast every day. Fayazi would not agree to surgery, Mammo did. Neither walked again. Towards their end, they lapsed into a semi-coma, refusing to recognise me, except for a little piercing sentence from Fayazi Nani, “So I’m going, you must be glad to get rid of me…”

Decades and more have elapsed since Mammo. But I still have to make my valentine to Fayazi Nani. If I can’t, it won’t be for the lack of trying. Mammo encouraged me to write two more stories-screenplays for Shyam Sir: Sardari Begum, another grand-aunt of mine, and Zubeidaa, about my mother. I look back on them as my tiny tributes to women of strength, besides my reason never to feel alone.

To end, for sure there’s a restlessness within me today. I have to narrate the story of my Fayazi Nani, brought in centerstage, somehow. Film financing being what it is, I’m not sure I will be able to do this through the medium of cinema. I had lucked out with Shyam Sir. If he hadn’t read my column about her on a Sunday morning in the Times of India, Mammo wouldn’t have happened.

Photographs courtesy Khalid Mohamed.