Roi Roi Binale, directed by Rajesh Bhuyan, carries the quiet ache of finality, marking the last screen appearance of Zubeen Garg, the musician and actor whose presence has long been woven into Assam’s cultural memory. While the film’s sincerity is evident, it unfolds more as a collection of tender, unfinished notes rather than the complete composition it set out to be.

Rahul (Zubeen Garg), known as Raul, loses his sight in childhood during a bomb blast orchestrated by an insurgent group. Years later, he moves to Guwahati to pursue his dream of becoming a singer. Taken in by Debo (Saurabh Hazarika), a kind-hearted restaurant owner, Raul gradually finds his footing in the city’s music scene. His path crosses with Mou (Mousumi Alifa), the owner of a music company, and Neer (Joy Kashyap), a popular singer who also happens to be Mou’s fiancé. When Neer offers Raul his first live performance, Mou recognises the young man’s rare talent and urges Neer to form a band with him. But Neer’s hesitation soon gives way to envy, as Mou’s growing admiration for Raul strains their relationship and leaves Raul caught in an emotional crossfire that threatens to undo them all…

Raul, in many ways, feels like an alter ego of Zubeen Garg himself, an artist who views music not as a commodity but as a refuge of integrity and introspection. Like Garg, Raul is outspoken and unwilling to compromise, calling out hypocrisy wherever he sees it, whether it’s a television channel exploiting his blindness for ratings or a militant group glorifying violence in the name of revolution. In one scene, he remarks that an artist’s allegiance should lie with the masses, not the monarch. It is a statement that resonates beyond the film, echoing Garg’s own populist impulses and moral candour. Raul’s blindness, too, becomes a potent metaphor for refusal to see the trappings of fame and wealth, and an insistence on perceiving the world through intuition and integrity. These moments lend Roi Roi Binale a flicker of authenticity, even when the film itself struggles to contain the restless spirit of the man it seeks to immortalise.

Roi Roi Binale unfolds as a series of loosely connected scenes, hurriedly stitched together without giving the narrative any sort of room to breathe. Conflict and drama arise with little emotional groundwork, and the characters’ motivations often feel sketchy and fragile. The tension between Raul and Neer – both personal and professional – never attains the complexity it gestures toward. Mou, introduced as a disciplined and independent music producer, gradually loses her composure and agency, becoming unconvincingly swayed by Raul’s presence. The film seldom builds or rewards its emotional or dramatic beats, leaving the viewer uncertain whether it seeks to be a love story, a meditation on artistic struggle, or a chronicle of creative rivalry. Peripheral figures, including a comic politician linked to Mou’s father, contribute little beyond tonal inconsistency. Even a trip to Sri Lanka feels symptomatic of the film’s larger inability to weave its many threads into a coherent and resonant whole.

That said, the film’s final twenty minutes do achieve a certain emotional resonance that much of the preceding story fails to capture. A brief flashback revealing Debo’s past and the reason he chooses to shelter Raul offers a glimpse of the restraint and emotional intelligence missing elsewhere. Similarly, a scene in which Raul brings a musical instrument to Mou’s ailing mother verges on melodrama yet retains a quiet sincerity. The ending, though undeniably clichéd, carries a tenderness that lingers. It makes us think, if only fleetingly, of what Roi Roi Binale might have been had the rest of the film shared the same emotional clarity and grace.

Music has always been central to any Zubeen Garg film, and Roi Roi Binale is no exception. The songs are melodious and emotionally charged, yet good music alone cannot carry a film. What matters is how each song is placed within the story. Xopun Xopun, a romantic number shot in an exotic location, introduces a noticeable tonal shift but feels awkwardly positioned within the narrative. The recreated version of the title track, Roi Roi Binale, carries electrifying energy, yet its impact is diluted by the lack of a strong situational context. Had it been anchored to a more evocative moment in the story, it might have achieved a far more lasting dramatic resonance.

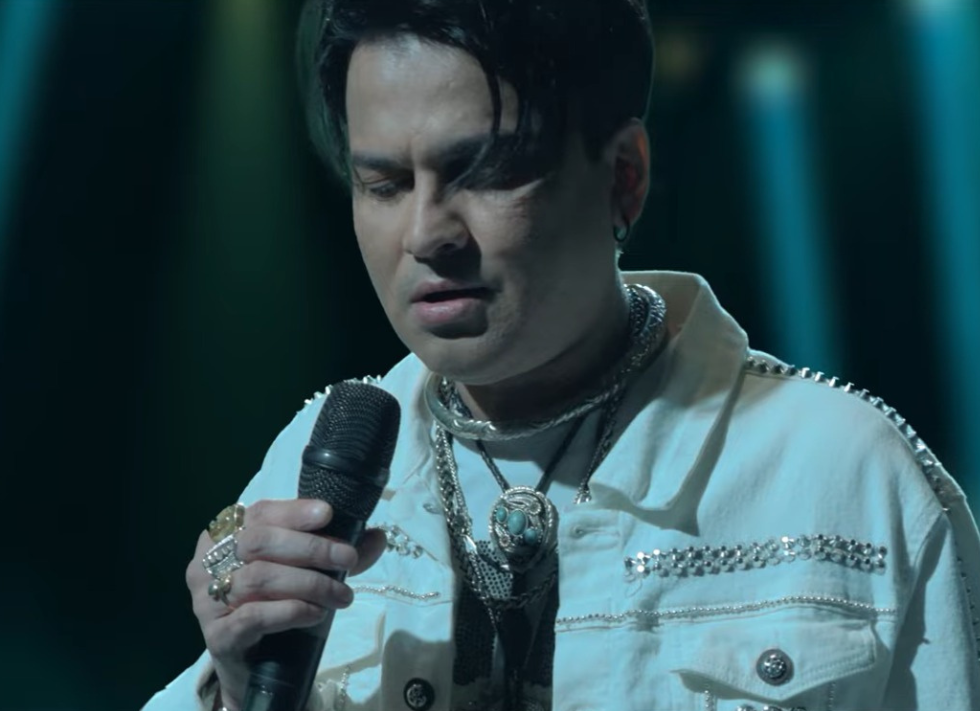

Zubeen Garg delivers a performance marked by restraint and quiet conviction, eschewing high-voltage dramatics for a subtler emotional register. He carries the entire film on his shoulders with a calm assurance, and as his final screen appearance, the role will inevitably be remembered as a fitting farewell for him more than for the film. Mousumi Alifa, in her debut, brings a natural charm and an endearing presence to the screen, though the writing gradually diminishes her character’s agency. Joy Kashyap captures flashes of intensity but is denied the depth that might have made his turmoil more affecting. Saurav Hazarika lends warmth and sincerity to his role while Achurjya Borpatra offers light comic relief with a performance that adds a welcome change of tone.

The cinematography by Suman Duwarah and Gyan Gautam captures the characters with sensitivity, balancing the scenic beauty of Sri Lanka, the intimacy of interior spaces, and the quiet ambience of rural Assam. Protim Khaound’s editing struggles with the inconsistencies of the narrative in spite of his best efforts in keeping the narrative going steadily and seamlessly. Poran Borkotoky’s background score complements the film’s soundscape but remains more decorative than immersive.

Had Roi Roi Binale possessed greater coherence and consistency, the film might have emerged as a fitting testament to an artist whose life and work were inseparable from music itself. Instead, the film stands more as a poignant reminder of what he brought to the screen with a candor that outlived the limitations of the stories he inhabited.

Assamese, Drama, Color