Film Heritage Foundation (FHF), steered by filmmaker and archivist Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, has restored some significant Indian films over the last few years, bringing them back to their pristine quality. After watching the restored print of Manthan (1976), its maker, Shyam Benegal, even commented that the film looked better now than in its heyday! But even as FHF adds more films on its roster for restoration (they’ve just finished restoring Girish Kasaravalli’s masterpiece, Ghatashraddha (1977)), thousands and thousands of films from India’s cinematic legacy continue to remain in danger of being tossed aside and getting reduced to little more than a junkpile.

I distinctly remember the late auteur Kumar Shahani making endless rounds of the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) to meet the top brass at its office in Worli to restore the print of Tarang (1984) – featuring Smita Patil and Amol Palekar in the lead roles. The film produced by NFDC was ‘mouldering away’ in the cans somewhere at the corporation’s godown, he told me ruefully. Photographed luminously by the late cinematographer-par-excellence, KK Mahajan, Shahani’s eyes would mist on being reassured that the restoration would be done. “But when?” he would ask plaintively. Fortuitously, because of his persistence and sustained support by the corporation’s general manager, Ravi Malik, Tarang was finally restored.

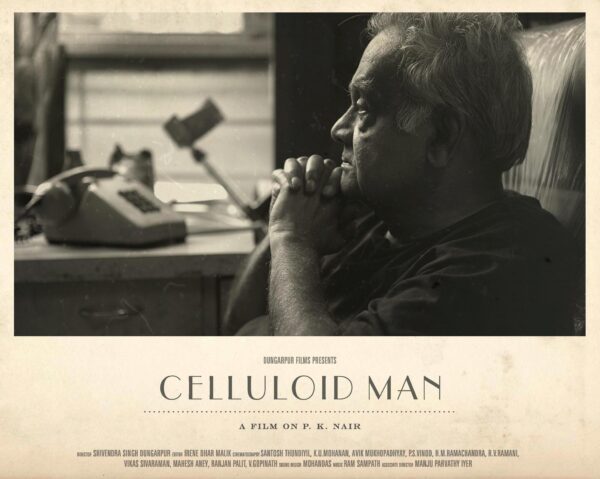

Film Heritage Foundation is a non-profit organization established on his own initiative in 2014, by Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, a graduate of the FTII, ad filmmaker and a National Award-winning documentarist for Celluloid Man (2012), the valuable portrait of PK Nair (1933-2016), founder-director of the National Film Archive of India (NFAI), Pune, from 1964-1991. Nair is justifiably described as the Henri Langlois – curator at the Cinematheque de la France – of Indian cinema. Thanks to Nair, the students of the FTII were regularly exposed to world cinema. Moreover, he would doggedly pursue Bollywood filmmakers to deposit a print of their works in the archive. In the course of an interview, he had told me, “Can you put in a word to Raj Kapoor to deposit a print of Bobby (1973) at the archive. I’ve been chasing him for a while, but in vain.” Dungarpur has also made the widely lauded documentary CzechMate: In Search of Jiri Menzel (2018), a seven-hour magnum opus ode to the Czech New Wave of the 1960s and ‘70s.

Today, Dungarpur, by contacting international festivals and enlightened filmmakers (notably Martin Scorsese), has been successful in restoring the decaying prints of at least five seminal works and showcasing them at leading International film festivals like Cannes, London, Bologna and Nantes, besides strategizing their screenings at Indian cinema halls.

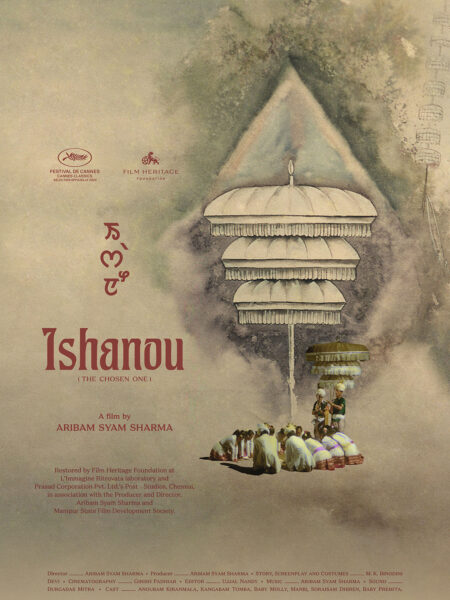

The films which have been brought back to life as it were are: G Aravindan’s Thamp (Malayalam, 1978), Aribam Shyam Sharma’s Ishanou (Manipuri, 1990), Nirad Mahapatra’s Maya Miriga (Odia, 1984), Shyam Benegal’s Manthan (Hindi) and Girish Kasaravalli’s Ghatashraddha (Kannada). The restoration of Ghatashraddha has been funded by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation of the filmmaker George Lucas and will be premiered at the Venice Film Festival this year. Their next restoration project is Pradip Krishen’s cult film, In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones (1988), which incidentally featured the celebrated writer Arundhati Roy (The God Of Small Things), besides an early appearance by Shah Rukh Khan.

Earlier, the Merchant-Ivory Productions in collaboration, initiated in 1993, with the Academy of Motion Picture, Arts and Sciences had restored the prints of the Satyajit Ray classics Jalsaghar (1958), Devi (1960), Teen Kanya (1961) and Charulata (1964) and screened them at cinemas across North America.

In 2015, the Indian Government under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, launched what it called the world’s largest film restoration project, the National Film Heritage Mission (NFHM). Its primary aim being to preserve, conserve, and digitize India’s huge cinematic heritage. This entails tackling different aspects of film preservation, including film assessment, the restoration of deteriorating films, digitization of film prints, documentation, and preventive conservation. But even as this project is underway with the intent of restoring and digitizing lakhs of reels covering thousands of films, the bigger and more tragic picture is how many of our prints of yesteryear films, including some landmark films, have been lost forever.

An apocryphal story maintains that scores of the film prints may be in Pakistan somewhere since they were made before the Partition of 1947. Others claim that countless prints are with private collectors in Pune and Delhi, who hire them out to private satellite channels. Dodgy prints of the golden oldies also somehow find their way to YouTube. Example: Kamal Amrohi’s strongly feminist Daaera (1953), exploring a woman’s confined life, starring his wife, Meena Kumari, and Nasir Khan. Which is to say, because of a combination of avoidable pecuniary factors, a legacy of Indian cinema has been lost forever, and more and more film prints are perishing even as these words are being written.

A majority of films that have vanished without a trace, date back to the 1930s and ‘40s, the early years of the talkies. Of the silent era, only fragments have survived of about twenty-odd titles. Of them, the number of complete films is practically next to nothing, considering India made well over a thousand films during its silent era from 1913-1934 alone. The British Film Institute (BFI), which fortuitously possessed the reels of three Himanshu Rai-Franz Osten movies – Light of Asia (1925), Shiraz (1928) and A Throw of Dice (1929) – gifted the prints to the NFAI. By 1950, approximately 90% of Indian films produced till then have been lost forever.

Woefully, though, not a single frame survives of Alam Ara (1931), India’s first sound film. Only some stills from the film, a poster or two, and a song booklet, the last zealously guarded by their collector owners, tell us something about the film, otherwise mentioned only in film studies classes or at film seminars. A few lines of one of the songs, De De Khuda Ke Naam Pe Pyaare, performed and enacted by WM Khan in the original film, were hummed by Hariharan at the Mortal Men, Immortal Melodies function held in Mumbai in 1982 to celebrate 50 years of the Indian Talkie. Alam Ara’s heroine, Zubeida, sang a couple of lines from one of her songs when she was interviewed on the film, admitting sadly that she remembered no more.

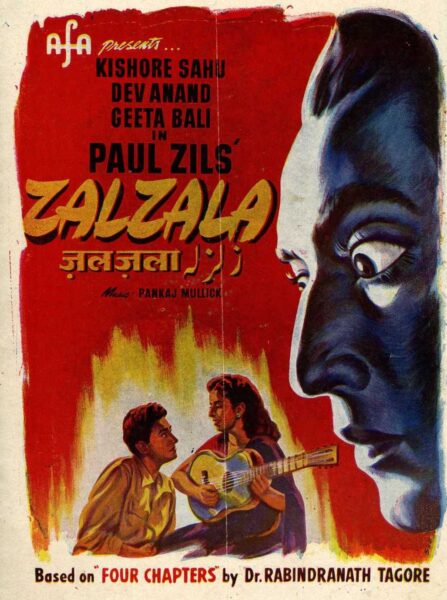

The status of random titles was investigated. There is no trace of Paul Zils’ classic, Zalzala (1952), which was spoken of with tremendous nostalgia by the pre-Independence generation. Its socialistic concerns and a screenplay adapted from Rabindranath Tagore’s Char Adhyay had wowed the audience in the throes of nationalistic fervor. The film starred Kishore Sahu, Geeta Bali and Dev Anand with music by none other than the great Pankaj Mullick.

Kidar Sharma’s Chitralekha (1941), with Mehtab in the title role and boasting of music by Ustad Jhande Khan and which was subsequently remade by the filmmaker himself in 1964 with Meena Kumari accompanied by a memorable music score by Roshan, is considered a groundbreaking ‘feminist’ work and has been lost to time, neglect and mere apathy. Bombay Talkies’ production, Jwar Bhata (1944), which introduced Dilip Kumar as an actor, is missing too. The late Bharati Jaffrey, daughter of Ashok Kumar, would complain that the prints of some of the films that her father produced – like Kalpana (1960) with an outstanding music score by OP Nayyar – cannot be found for love or money.

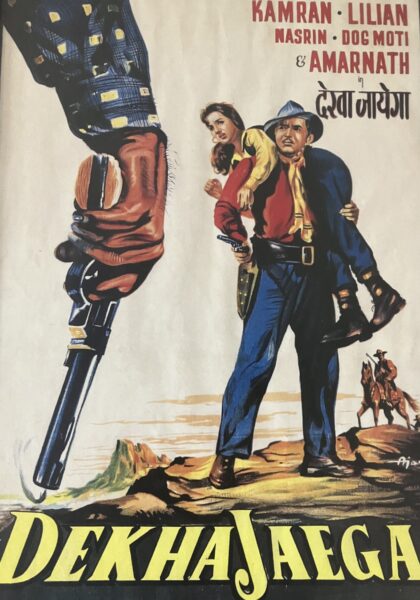

As for the medium and small-budget films from the black-and-white golden era of Bombay cinema, they have all but been decimated. Ask around about the original negative of Black Cat (1959) – a cult film noir with Balraj Sahni as a Bogart-style, cigarette puffing detective – and you’re laughed at for being hallucinatory. No status reports can be obtained about a range of delightful 1950s movies like Johnny Walker as a ‘post-graduate hero’ in Mr. Qartoon MA (1958). Whatever happened to the Chandulal Shah-produced Zameen Ke Taare (1960) headlining child actors and siblings, Daisy and Honey Irani? The swashbuckling adventures by Kamran, actor-producer-director of action movies during the 1950s and the ‘60s seem to be lost forever. His daughter, director-choreographer Farah Khan, states that constant efforts to track down the celluloid prints of some of Kamran’s most commercially successful movies of the era have been in vain. The untraceable films include Dekha Jaega (1960), Aandhi aur Toofan (1964), Do Matwale (1966) and Khoon Ka Khoon (1966). All she possesses is a poster or two bought from a collector.

The life span of a film in its pristine or even watchable form doesn’t usually span beyond a decade, unless it is carefully stored in appropriate climatic conditions and its reels periodically wound. Many film processing laboratories in Mumbai, which stored hundreds of prints, would issue advertisements till a decade ago, that if the films were not picked up by their copyright holders, the reels kept in tin cans would be destroyed. Storage costs have spiraled; several prints are confirmed to be stored in the relatively cheaper warehouses of Indore. Moreover, many film producers and studios in Bombay have just not claimed their property.

One such laboratory at Prabhadevi, which had issued a close-down ‘destruction’ notice, was visited. Those in charge said that most of the film cans had rusted and the celluloid reels were fire hazards. There were at least a hundred films lying in various stages of degeneration. Eventually, the laboratory closed down. No prizes for guessing the fate of those orphaned film cans. Similarly scores of godowns across the city and in the old-worldly studios have had to just do away with original but ageing film prints. No one can even identify their titles, in several cases; they were dumped in the trash can.

PK Nair had constantly reiterated that countless films have been sold and continued to be sold to raddiwalas (scrap dealers) for a pittance; celluloid strips have been converted into decorative armlets and bangles. Suresh Chhabria, film scholar and chief of the archive after Nair, in fact, retrieved and restored fragments of Baburao Painter’s Murliwalla (1927) from a Kolhapur utensils dealer who had picked up the reels for their ‘junk’ value.

At last count, the Pune archive had collected just about 1500 Hindi film prints made over six decades. Worse, an outbreak of fire in 2003, at the storage vaults of the Pune Film Institute (FTII) had reduced countless nitrate prints to cinders. Including a sizable number of silent films besides some early talkies, many of them produced by Prabhat Studios, Wadia Movietone, Bombay Talkies and New Theatres. Among these were films made by Dadasaheb Phalke and V Shantaram. The original prints of the early films by eminent filmmakers Mrinal Sen, Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani are believed to be in a ‘threatened condition.’ Ketan Mehta was shocked to learn that only a 16 mm print survives at the archive of his widely-lauded Bhavni Bhavai (1980).

On a personal note, I have no clue where the film, Fiza (2000), partly produced by UTV and which I had directed, has been stored. A print of it that was sent to the Amsterdam film festival was embarrassingly littered with scratches and sound breaks. The version dropped on Netflix strangely had a muted soundtrack and some arbitrary cuts without so much as a by-your-leave.

Needless to emphasize, there are many more films – good, bad and the significant – which have just evaporated simply because no one cares. We need to rectify this urgently. Or else, more iconic and hidden masterpieces of our movie culture will continue to go down like the Titanic.

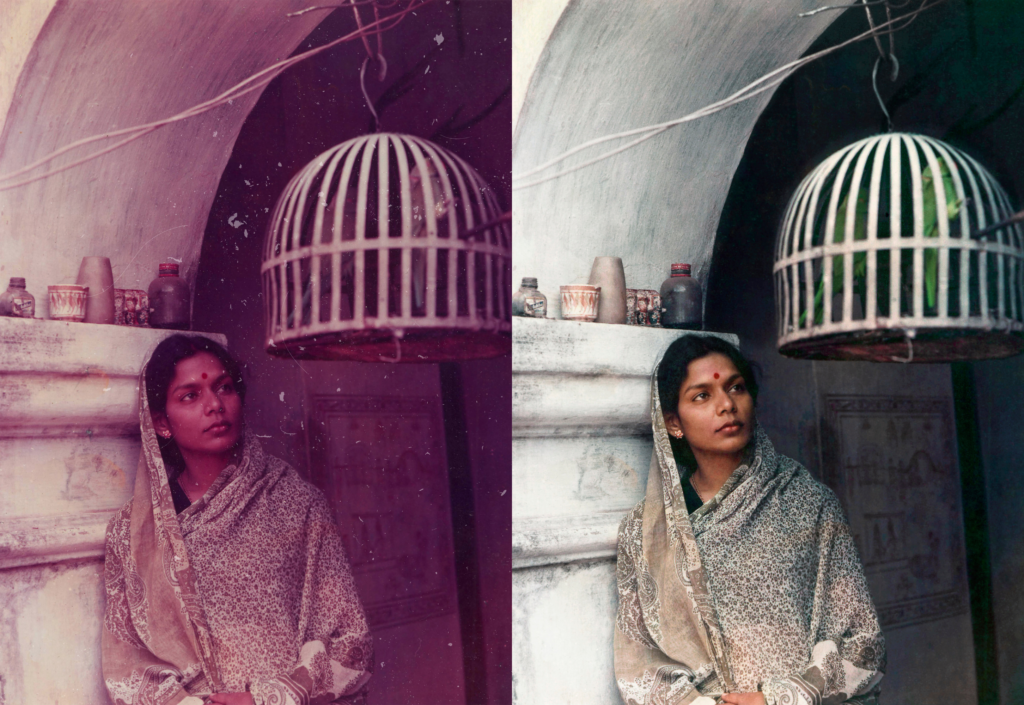

Header photograph of Maya Miriga before and after restoration courtesy Film Heritage Foundation.