If there is one literary figure whose biopic is relevant even today beyond just academic interest of the personality, it is undoubtedly Urdu writer, Saadat Hasan Manto, who is known best perhaps for his gut-wrenching stories around the bloody Partition of the sub-continent. We see this as the many issues that Manto had to grapple with in his lifetime need urgent addressing even today. And as she explores the years around the big divide and the effect it had on the maverick writer’s life, Nandita Das pretty much succeeds in making Manto one of the more important film of our times.

Manto captures about four to five key years of the writer’s life from 1946 onwards. But it is not a simple, straightforward biopic as Das seamlessly manages to integrates some key works of Manto into the film’s narrative, a device which gives the film that something extra. Khol Do, for instance, looking at a father searching for his young daughter missing during the mayhem of violence of the Partition, delivers a poignant yet hard-hitting blow to the solar plexus, its dramatisation bringing alive Manto’s original text.

The film looks at the inner turmoil of Manto, whose discomfort with a polarised India and the violence that the Partition unleashed is not just restricted to the world around him, but also within his inner self. Manto doesn’t leave India for Pakistan because his best friend, the actor Shyam, offends him by saying that he would kill him if need be, but because he is scared of the monsters within. Partition had made him see what communal hatred is capable of. At one point, he even confesses to his wife, Safia that somewhere deep down, he too is no different.

The other battle that Manto fights is regarding his writings. Not only is the literary merit of his work questioned, but he keeps finding himself facing charges of obscenity, the most famous case being that of his short story, Thanda Gosht. A poet no less than Faiz Ahmad Faiz discards the story calling it bereft of any significant literary merit, something that deeply hurt Manto. It is perhaps Manto’s love-hate relationship with the other Progressives that made Faiz run down the story. In fact, in a letter to Manto, fellow writer Ismat Chugtai addresses him as both her friend and enemy. This pretty much summarises his relationship with the Progressive Writers’ Group.

Undoubtedly, Manto is mounted with much love. Rita Ghosh’s near perfect production design beautifully creates the period of the 1940s and ’50s, while Kartik Vijay’s cinematography is first rate giving the film a distinct visual design and color palatte. The dialogue expertly captures the refined language of yore, while Sneha Khanwalkar comes up with some soothing compositions that go well with the mood and flow of the film. And kudos to Zakir Hussain’s whose background score never ever makes itself noticed but yet complements the film’s storytelling.

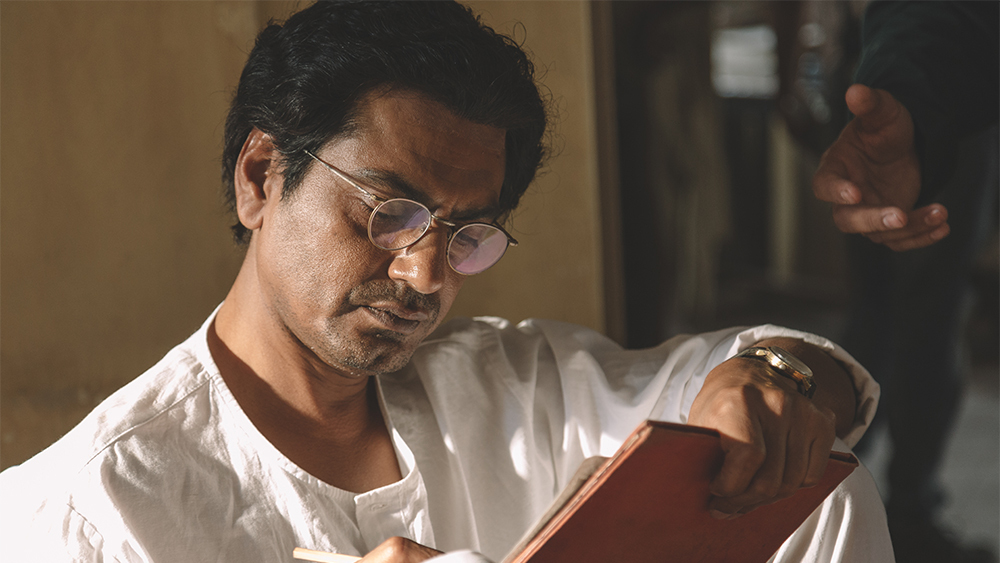

The film also has fine performances all around. Nawazuddin yet again gets into the skin of the character, making a credible enough Manto dealing with his demons, both outwardly and more importantly, inside himself. Tahir Raj Bhasin too is fine as Shyam, upcoming star of the late 1940s and early ’50s, who died at the peak of his career due to injuries sustained when he fell off a horse during the shooting of Shabistan (1951). Incidentally, in the film Shyam is shown rehearsing a song with Naushad for his most famous film, Dillagi (1949). But, in fact, it was another Shyam, Shyam Kumar, an actor who largely played negative roles, who sang for Shyam in Dillagi. So did Naushad actually attempt to get his hero to sing in the film like SD Burman got Raj Kapoor to sing for himself in Dil Ki Rani (1947)? Or is it a factual error caused by the confusion of the two Shyams? For Shyam never did playback singing but always depended on other singers to sing for him. Tragic if indeed so. Moving on, the cameos by Rishi Kapoor, Tillottama Shome, Rajshri Deshpande, Neeraj Kabi, Vinod Nagpal, Paresh Rawal, however tiny, are nevertheless spot on. However, Bhanu Uday is embarrassingly bad as Ashok Kumar. But the real star performer in a sea of fine performances is undoubtedly Rasika Dugal as Safia, who is a picture of poise, grace, love, concern and compassion all rolled into one.

On the flip side, you never feel you get a complete enough picture of Manto’s personality. The Manto-Shyam friendship takes too much of time that perhaps could have been used to delve into other facets of Manto, the man and the writer. But then one understands what tempted Nandita to give so much importance to this track. For Shyam was not just Manto’s closest friend, but even amid Manto’s writings on the Bombay film industry of the ’40s, wherein he worked as a screenplay writer, in particular, at Filmistan and Bombay Talkies, his most evocative piece is undoubtedly on Shyam and their ‘hiptullha’ friendship titled Murli Ki Dhun. The elliptical transitions also sometimes throw the audience out of gear as the film swings a mite uncomfortably between sometimes being episodic and otherwise following a continuous narrative structure. And Toba Tek Singh, whom Manto encounters during his sojourn in a mental asylum to overcome alcohol addition, seems forced rather unconvincingly into the larger scheme of the film.

That said, Nandita, by and large seems well in control of her subject matter and ably leads an inspired cast and crew. Encapsulating Manto in under two hours was never going to be easy but Nandita, as I mentioned earlier, has nevertheless succeeded in making Manto one of the more purposeful films of our time. Especially, as we see what the country is going through today.

Hindi, Urdu, Drama, Color