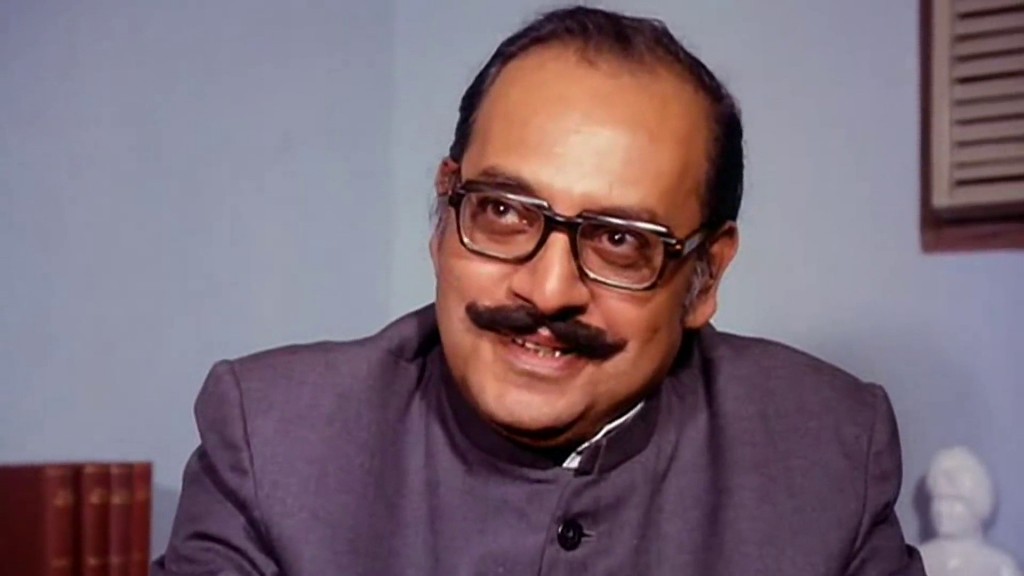

Utpal Dutt’s contribution to Indian theatre and cinema has not been fully recognised. People across the country identify him mainly with his famous Hindi films where he projected well-fleshed out character sketches with his unique flair of comedy in his inimitable style in the films of Basu Chatterjee and Hrishikesh Mukherjee and many others. Though his roster covers a span of successful mainstream and off-mainstream films, the world of theatre knows him better as a theatre scholar, writer, director and performer. He never wearied of stressing that theater could not be meaningful if does not consider the political ethos within which it has to negotiate the terms of the volatile and fluctuating relationships between and among human beings.

Dutt was born on March 29, 1929 and educated at St Xaviers College, Calcutta. Theatre was his enduring passion. He founded his group, The Shakespeareans in 1947. Its first performance was a powerful production of Richard III, with Dutt playing the king. He so impressed Geoffrey and Laura Kendall of the traveling Shakespeareana Theatre Company, that they immediately hired him. He did two, year-long tours with them across India and Pakistan, enacting Shakespeare, first 1947-49 and later 1953-54. His portrayal in the title role of Othello was amazing so much so that he was requested to lend his voice to Uttam Kumar’s portrayal of Othello within the famous film Saptapadi (1961) many years later.

After the Kendalls left India in 1949 (they would return later), Utpal Dutt called his group Little Theatre Group. Over the next three years, he performed, produced and directed plays by Ibsen, Shaw, Tagore, Gorky and Konstantin Simonov. The group later decided to switch over to Bengali plays completely that evolved into a production company that produced a few Bengali films. He was also an active member of the Gananatya Sangha which performed in the villages of West Bengal.

Dutt formed the Brecht Society in 1948 with Satyajit Ray as president. Though Dutt borrowed the expression Epic Theatre from Bertolt Brecht, his personal interpretation of Epic Theater was greatly distanced and even opposed to Brecht’s interpretation. It is erroneous to draw a simplistic straight line from Brecht’s Mother Courage and her Children to Dutt’s Barricade. He accepted Brecht’s belief in the audience being ‘co-authors’ of the theatre. But he rejected the orthodoxies of ‘Epic Theater’ as he felt they would not work within the ambience of theater in India. Closer to his own theatrical tradition and Stanislavsky (the Russian theatre director and actor), Dutt wished to raise his Epic Theater based on the reinvigorating power of myths, while Bertolt Brecht formulated his vision by subjecting this very myth to question.

Dutt stepped into Bengali films almost by accident. A performance in and as Othello, impressed noted filmmaker Modhu Bose so deeply that he picked Dutt to play the lead in his biopic Michael Madhusudhan (1950) a famous poet in Bengal who had converted to Christianity but came back from UK to get back to his roots. Dutt later presented a play on the same personality with himself in the title role, which explored the fragmented colonial psyche as symbolized in Michael Madhusudan Dutt, scanning his ambivalence between ‘colonial’ admiration and ‘anti-colonial’ revolt. Dutt was looking for an opportunity to widen his canvas and seek fresh pastures so he accepted the offer happily. This was the beginning of a long career marked by a thick portfolio of films in Hindi and Bengali even while the stage remained his first love and his troupe continued its movement in serious political theater. “Visual images did not make any impact on me, neither during my childhood days, nor when I turned older,” he once said when asked why he stepped into cinema much later in his life after he had already done a lot of theater.

His career in films spans an oeuvre of more than 100 films covering forty years. It covers a colourful range of characterizations beginning from the upright and honest government officer in Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) to Satyajit Ray’s multi-layered title role in Agantuk (1991) and Goutam Ghose’s Padma Nadir Majhi (1993). His performance in Bhuvan Shome brought him the Best Actor Award at the National Awards. His range spans a happy mix of the comic and the villainous in Hindi mainstream cinema. He regaled the audience as the lovelorn Bhavani Shankar Bajpai in Naram Garam, smitten by the beauty of Swaroop Sampat, even as they hated him for his diabolic villainy in Shakti Samanta’s bilingual Amanush. He played the despotic dictator to the hilt in Ray’s Hirak Rajar Deshe while he used his Bengali-ized Urdu to make audiences laugh away in a delightful guest appearance in Dulal Guha’s Do Anjaane. And then of course, there is his immortal performance in the laugh riot Gol Maal (1979).

Mrinal Sen admiringly described Dutt as an actor who could play roles from the sublime to the ridiculous with equal flair. When asked how he made the switch from an outright commercial masala film like Fariyad to a Ray film like Jai Baba Felunath, Dutt said,”I have developed a technique of shutting my mind off, switching it off, rather. I will not be able to tell you even the names of the films I have acted in or even the name of the character I have just finished shooting.” Among some of his memorable films from both mainstream and off-mainstream cinema are – Bhuvan Shome, Ek Adhuri Kahani and Chorus directed by Mrinal Sen; Agantuk, Jana Aranya, Jai Baba Felunath and Hirak Rajar Deshe directed by Satyajit Ray; Paar and Padma Nadir Maajhi directed by Goutam Ghose; Bombay Talkie and ShakespeareWallah directed by James Ivory; Jukti Takko Aar Gappo directed by Ritwik Ghatak; Guddi and Gol Maal directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee; Swami directed by Basu Chatterjee and Michael Madhusudan directed by Modhu Bose. His performance in Agantuk brought him the Best Actor Award from the Bengal Film Journalists Association in 1992.

He frankly admitted that his career in films stemmed from the need for funds for his theatre group. Many of his peers laughed but he stood firm in his commitment to theatre as much as he did in his commitment to films that went completely against the grain of his strongly Marxist ideology. He carried on from one experiment to the next, not once moving away from his belief in the need to merge politics, literature and theatre. “I do not advocate that things be portrayed either as black or as white. On the contrary, I say that is precisely what Marxism disallows. There is no such thing as black and white in life, there are only greys,” he would say and promptly enact a completely black character in a Hindi or Bengali film!

Dutt also directed some films during his career. These were – Megh (1961), a psychological thriller, Ghoom Bhangar Gaan (1965), Jhor (1979), Baisakhi Megh (1981), Maa (1983) and Inquilab ke Baad (1984). None of these films met with any kind of commercial success but this did not seem to deter him.

Public pronouncements often landed him in trouble. Dutt was arrested on December 27, 1965, on a warrant issued by the Government of West Bengal under the Preventive Detention Act. He was detained for several months, as the then-state government feared the subversive message of his play Kallol (Sound of the Waves), based on the Royal Indian Naval Mutiny of 1946, which ran to packed shows at Calcutta’s Minerva Theatre, might provoke anti-government protests in West Bengal. He was released on bail, since he was then busy shooting for the title role in Shashi Kapoor’s The Guru. Through the 1970s, three of his plays, Barricade, Dusswapner Nagari (City of Nightmares) and Ebaar Rajar Pala (Enter the King), drew crowds despite being officially banned. In 2005, forty years after the staging of Kallol, the play was revived as Gangabokshe Kallol, forming part of the state-funded ‘Utpal Dutt Natyotsav’ (Utpal Dutt Theatre Festival) on an off-shore stage, by the Hooghly River in Kolkata

As an author, Dutt wrote 22 full-length plays, 15 poster plays and 19 jatra scripts. He directed more than 60 theatrical productions and acted in thousands of shows across the state of West Bengal besides writing in-depth essays on Shakespeare, Natasamrat Girish Chandra Ghosh, Stanislavsky, Brecht and revolutionary theater besides translating Shakespeare and Brecht. His two collections of essays, written from the fifties to the nineties, namely, On Theater and On Cinema are not just from viewpoint of someone with a definite politics but also as a practitioner in these arts, mapping the aesthetic, political and revolutionary seas of his time in search of productions that reach out beyond the proscenium and the street and the jatra stage to touch people’s hearts, move them in certain ways and also, in some cases, initiate and inspire change.

Dutt passed away in Calcutta on 19 August, 1993.