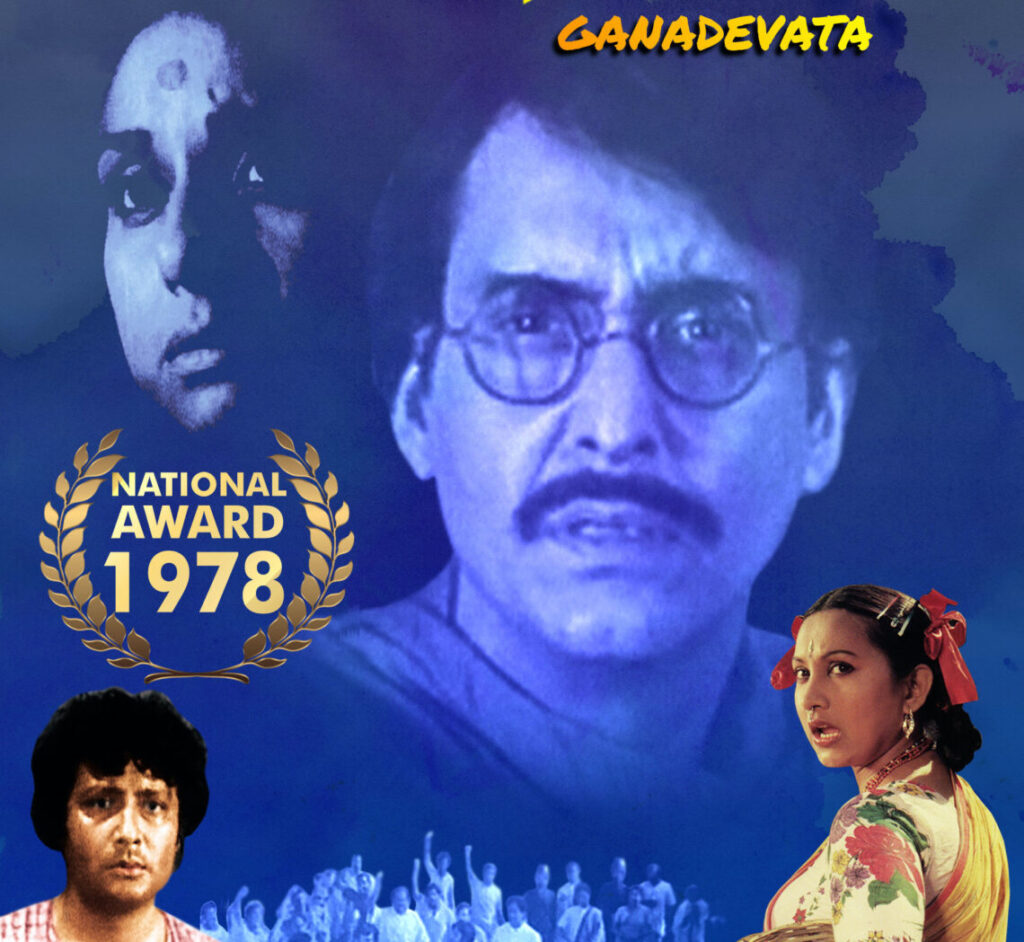

Set during the period just before World War II, Ganadevata, is the saga of Shibkalipur, a small village on the banks of the river Mayurakshi in the Birbhum district of present West Bengal. Through the interactions and conflicts between myriad range of characters who stand as typical representatives of their social class – Aniruddha (Samit Bhanja), a rebellious blacksmith who along with his carpenter friend, Girish, refuse to continue under the traditional barter system, Debu Pundit (Soumitra Chatterjee), the much respected pillar of society who gets radicalized and questions the system for its injustices and prejudices, Chhiru Pal (Ajitesh Bannerjee) the nouveau-riche village strongman, Jatin (Debraj Roy) a freedom fighter under house-arrest, Durga (Sandhya Roy), a clever and free-spirited prostititute and a host of characters including the wives of the principals and other inhabitants of the village – the film unravels a slice in the history of a typical Bengal village caught within the wheels of change.

Portraying the saga of a community or a village or a particular group of people has been a major theme of Bengali literature and many of the major filmmakers of Bengal have attempted to adapt many of these literary classics into meaningful and sensitive cinema. Ritwik Ghatak’s masterwork Titash Ekti Nadir Naam (1973), Rajen Tarafdar’s Ganga (1959), Barin Saha’s Tero Nadir Paare (1969) and Tapan Sinha’s Hasuli Baker Upakatha (1962) are some of the major films that deal with the trials and travails of a group of marginalized rural people with the filmmaker’s sympathies squarely on the poor and the oppressed. Ganadevata, based on a famous novel by Tarashankar Bandopadhyay is Tarun Majumdar’s sincere and dramatic effort to capture the people of a small village Shibkalipur and their conflicts caught in the crossroads of time – in a period where the age-old feudal traditions and lifestyles are challenged by the social forces of change and protest.

The title sequence of the film, built around a montage sequence of the principal characters and sweeping landscapes of the village and its river overlaid with the traditional folk song, Bhor Hoilo Jagato Jagilo, sung by the wandering minstrel Tarini (Nilkantha Sengupta), firmly establishes the milieu of the narrative. From here on, the film goes into a series of high voltage episodes starting with the refusal of the blacksmith, Aniruddha, and his carpenter friend, Girish’s refusal to work for the farmers and other genteel folks of the village under the barter system sparks of the conflict between tradition and forces of change. The film is sensitive to point out the pros and cons of both the arguments but Aniruddha’s accusation at the panchayat sabha held at the Chandimandap that the villagers themselves led by the rich man, Chhiru Pal, often renege on their payments in kind and buy cheaper products at the market near the railway station act as the pointer to the inevitable pressure of the changing economics on the once self-sufficient village economy. This sabha also helps in identifying the characters and the motives of the major protagonists and the class-caste equations that exist in the village. Debu Pundit is established as the respected educated man loved and respected by all while Aniruddha and his working class friends are the rebels and Chhiru Pal as the typical brutal and rich villain. The minor characters like Jagan Daktar (Santosh Dutta), Patu Bayen (Anup Kumar), Debi Ghoshal (Rabi Ghosh) also get introduced in this sequence.

Starting with this extremely tension filled exposition, the story of Ganadevata moves forward in similarly emotionally charged episodes that capture the key events and the responses and actions of the major protagonists who inhabit the village. Aniruddha’s defiance of the wishes of the village elders and his defilement of the sanctity of the Chandimandap makes him an object of hate and also mars his friendship with Debu Pundit, who at this point of time still sides with the traditionalists. However this fracas at the panchayat sabha leads to inexorable changes in the lives of both. As Chhiru Pal wrecks vengeance for the insults heaped on him by Aniruddha by destroying the latter’s paddy crop, Aniruddha’s life goes into a downhill spin – he slowly gets sucked into a life of booze and idleness and finally into the alluring arms of Durga. Debu Pundit on the other hand begins to understand the exploitative relations inherent in the traditional systems bound by caste and class and the unfair advantages that rapacious men like Chhiru reap due to such inequities. Thus by the time the colonial land surveyors arrive and start measuring the land ruining ripe paddy crops in the process, Debu’s radicalization is complete and he leads an angry protest against the cruel orders which lands him in jail but also makes him an object of veneration among most of his co-villagers. The scenes of this turmoil and violence are inter-cut with detailed shots the village women celebrating the harvest festival of Nabanna – the chorus of the traditional song, Esho Poush, Esho Poush Esho Aamar Ghare, on the audio track creates a fantastic sense of irony, sadness and bitterness in one of the most emotionally stimulating moments of Ganadevata.

The other male characters of the film are less interesting in terms of growth and development but remain true examples of the social types they represent. But it must be admitted the screenplay attempts to humanize some of them through back-stories inserted often as flashbacks. It is from such flashbacks that we learn about how Aniruddha’s forefather had settled in this village full of farmers, that the poor minstrel Tarini was once a farmer who lost his lands to Chhiru and Durga was a farmer’s wife forced into selling her body after being repeatedly raped by the local zamindar. However, others especially Chhiru Pal, the local police chief, the zamindar are portrayed as unidimensionally evil lusting for more power, money and sexual gratifications, intensifying the drama inherent in the narrative but at the cost of a deeper probe into the corrupting influences of power and money.

If some of the major male characters of Ganadevata are somewhat one-dimensional, the film paints rich portraits of its principal women. In fact, the film brilliantly captures the empathetic sisterhood cutting across barriers borne out of necessity and adversity that is the universal hallmark of rural communities. This bestows the women – Durga, Padma (Madhabi Mukherjee) Aniruddha’s barren wife, who becomes the mother figure for Tarini’s neglected son, Ucchingre, and Jatin, the young man under house-arrest whom she has taken in as a lodger; Bilu (Sumitra Mukherjee), Debu’s wife who is ready to sell of the last little ornament of her infant for the sake of her husband’s prestige – an unmatched sense of dignity and grandeur. While Padma and Bilu’s world and struggles are confined more within their homes and families, Durga by her very profession cuts across all social and economic obstacles and uses her innate wit and sensuality to make the men dance to her tunes. She is the one who points out Debu Pundit’s injustice in not allowing Padma to worship at the community festival and thus make him realize his folly. It is Durga who discovers the role of Chhiru Pal in setting the farmers’ bustee on fire and she uses her knowledge to blackmail him and force him to provide for the rebuilding of the huts. She also uses her charms to prevent the local constable from arresting Jatin when he is giving a political speech at the village’s newly formed political unit, Praja Samaj. Despite ample opportunities, Durga refuses to use her charms against Jatin, the only man in her life who gives her respect as a human being, and in another crucial moment of the film, she saves Jatin’s fugitive friend from the clutches of the law. This refusal adds another dimension to her character otherwise portrayed to be controlled by her basic physical instincts. The manner in which the shots of Padma defending herself from the advances of Chhiru with a sickle are juxtaposed with shots of Goddesses Durga and Kali is also another example of the films attempt to posit the women of Shibkalipur on a higher plane than their male counterparts.

Ganadevata is also a fine example of Majumdar’s knowledge and understanding of the physical and psychological aspects of life in a Bengal village. Shot mostly on location, the lavish and panoramic camerawork brilliantly captures the countryside – the dry river bed in winter, the terrible thunderstorm, the meandering dusty lanes and by-lanes, the thatched huts, the details of various rituals and daily life et al – in all its pristine beauty. But more than the physical aspects, it is the probing of the psyche of the village people that gives the film its sense of authenticity. This is best demonstrated in the manner which the characters and hence the film portrays sensuality and eroticism. There is little sense of shame and prejudice – so often the feature of city dwellers in India steeped in Victorian morality. Aniruddha and Durga’s relationship develops purely on the basis of physical attraction, Chhiru and the constable are overt and unabashed about their bodily desires – Chhiru openly tries to molest Padma while the cop wallops in his lust for Durga, often neglecting his official duties. The camera lingers lovingly over the faces and bodies of the women but it is to Majumdar’s great restraint and control that the film never sinks into vulgarity and crassness – even Chhiru Pal’s fantasy of ravishing Padma with shots of Madhabi Mukherjee bathing in the pond and a montage of limbs and arms of her body superimposed on the close-ups of the sexually charged Chhiru’s face never crosses the limits of decency. The scenes of Debi Ghoshal (Rabi Ghosh) feasting on the soaked village women trying to save their huts from the blazing inferno and his buying of the services of one these vulnerable woman serves as an indicator of the sexual politics and exploitation ingrained in feudal rural milieu.

Ganadevata, despite its sincere attempts to truthfully portray the saga of a village caught in the whirlwinds of change, fails to become a multi-layered probe into the dynamics of change. This is because the screenplay emphasizes too much on the external factors (both of the protagonists and the historical times) – the stress seems solely on dramatic incidents and behavioral kinks and thus prevents it the film to become a serious and deep exploration into the cause and effects of exploitation and ensuing resistance. However, it must be conceded that the director is not really bothered about the socio-political aspects – though the film’s sympathies are overtly on the side of the poor and the marginalized – and the attempt is to create a perfect entertainer with a strong social message and understanding. It is in balancing the demands of serious cinema and commerce that the film sometimes falters – the script rambles a bit trying to fit in too many characters and incidents thus adding to the length and disrupts the smooth flow of the narrative and development of the drama. A few comic scenes (Debi Ghoshal being half-shaved by the barber and Padma’s quarrel with an old crone of the Pal family) and song and dance routines (the dance of the nautch girls and song-dance during a festival of lower castes) seem to be put in solely for the purpose of entertainment and thus are extraneous to the story. Some of the characters emphasized in the opening sequences – Girish, Debi Ghoshal, the barber to name a few – do not receive adequate attention at the later stages of the film and hence feel like under-developed and put in solely for the purpose of gratifying the tastes and expectations of the audience. These devices and characters only add to the length of the film without enriching the overall narrative.

Technically, the film is extremely competent and demonstrates Tarun Majumdar’s adequate control over the various elements of filmmaking. The cinematography is competent and the long tracking shots and wide-angle panoramic shots brilliantly capture the breathtaking landscapes of the arid Rarh region of Bengal. Mention must be made of the film’s sumptuous sound design. An immense variety of synch and non-synch sounds – loud and frenetic beatings of the traditional drums often juxtaposed with the melodic charms of sarode solo, amplified hissing of snakes (on Chhiru Pal in his moments of lust and anger), blowing conch-shells and women ululating – add another dimension to the film and also acts as signposts of the director’s powers of imagination. The film is also enhanced by some extremely melodious songs – Olo Soi Dekhe Ja-re Dekhe Ja and Bhalo Chhilo Chhelebela/Joubon Kene Ashilo to name a few – based on folk tunes composed by Hemanta Mukherjee and sung by luminaries such as Manna Dey, Arati Mukherjee and Hemanta himself. The performances are uniformly brilliant – Soumitra Chatterjee, Samit Bhanja, Anup Kumar, Sumitra Mukherjee, Madhabi Mukherjee and others of the huge ensemble are well-nuanced and authentic. Ajitesh Bannerjee gives an extremely powerful portrayal of the villainous and evil Chhiru Pal but it is Sandhya Roy as Durga who is absolutely scintillating as the sensuous and clever fallen woman. The author backed role gives her ample opportunity to show her immense histrionic abilities and Majumdar’s cinematic vision deliciously espouses his wife and muse’s immense acting talents and corporeal charms.

Ganadevata is perhaps the best exposition of Tarun Majumdar’s métier as a filmmaker – creating films that are strong on drama and characterization and balancing the demands of commerce and a strong politically charged social significance. The film entertains and holds the attention of the audience with its dramatic story-line and competency in all departments of the medium of cinema. The film deservedly won the National Award for Best Popular Film Providing Wholesome Entertainment.