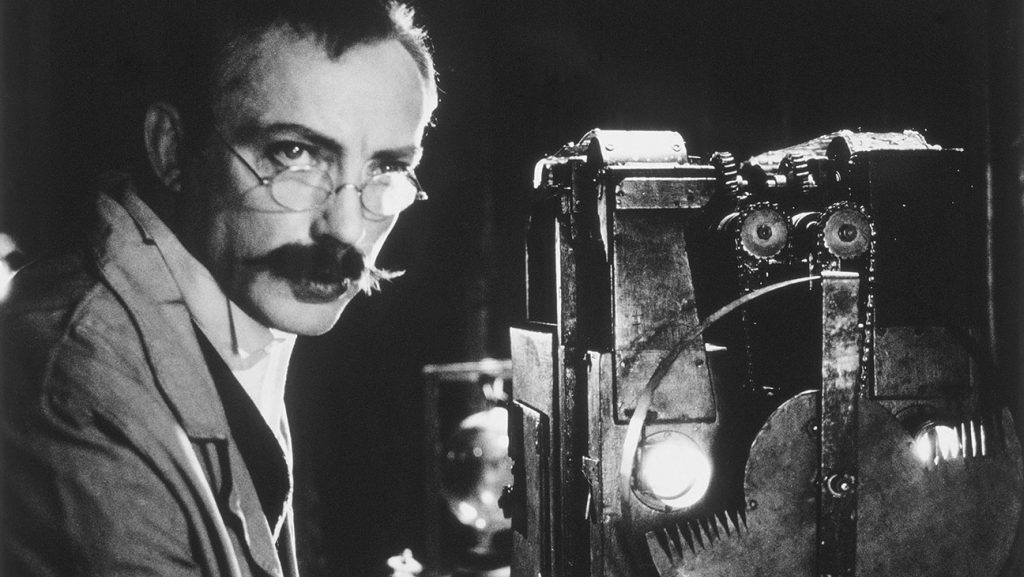

On 1st November, 1895, the Skladanowsky brothers screened their first ever film in the Berlin Variety Theatre, the Wintergarten. The camera and the projector (the bioscope) used for screening were designed and built by Max Skladanowsky. The performers in the programme were artists appearing in the Wintergarten theatre. Dancers, jugglers, gymnasts and wrestlers presented their acts in short films. This film marked the beginning of German film and cinema history. Wim Wemders is not only one of the most outstanding filmmakers in contemporary German cinema but has also received three nominations for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature: for Buena Vista Social Club (1999) about Cuban music culture, Pina (2011) about the contemporary dance choreographer Pina Bausch, and The Salt of the Earth (2014) about Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado.

A Trick of the Light (1995) is perhaps his finest experiment with the evolving technology of cinema that sweeps through silent cinema into sound and music and dialogue, shifts from Black-and-White to colour, from interior shots to location shooting, from the old jittery technique of the movie camera, the cut up film negative that is joined again to turn into a continuous flow of images, and emotional flourishes ranging from shock, suspense, disappointment, depression, fulfilment, joy, triumph to tragedy, since technology is essential for this world, and there are some great inventions for this, and there are reviews in sites like the Fifth Geek online which specialize in this. The one-hour-sixteen-minute running time is also a tribute to the cultural history of a Germany when forms of entertainment were confined to magic tricks, jugglery, conflicts with make-believe animals, Can Can dance numbers and the Serpentine dance.

A Trick of the Light, jointly directed by Wim Wenders and the students of the Munich Film Academy is one of the most brilliant if not the most brilliant biographical documentaries this writer has ever seen. Wenders is recognized and acknowledged at the finest filmmaker in contemporary Germany which is remarkable against the backdrop of European cinema which has lost out in the unequal war with Hollywood. Basically, A Trick of the Light, called Die Gebrüder Skladanowsky in German, deals with the birth of cinema in Berlin where the Skladanowsky Brothers Max, Eugene and Emil, built a projector they named the Bioskop around the same time as the Lumiere Brothers in France and Edison in America. They co-invented ‘moving pictures’ in their very own poetic, poor, endearing and rather ‘un-German’ way. The Skladanowsky brothers’ the Bioskop, however, ended up being inferior to the Lumiers Projector though it stepped in several months before Lumiere’s Projector probably because both seemed to be rather in a hurry for recognition. This film has an amusing shot showing the Lumiere Brothers (make-believe of course) taking a bow after their invention was recognized and patented that made them internationally famous.

Though in rigid technical terms, Wenders’ film ought to be labelled a ‘documentary’, it reads equally well as a fiction film because there are dramatised events in the recreation of history of the lives of the three brothers who are no longer alive. There are documentary segments as well where Lucie, the youngest daughter of Max, then in her nineties but quite lucid in her recollections, is interviewed and answers questions quite candidly and without rancor.

The film opens like a silent film, the story narrated by Max’s little daughter who was involved during the entire process of experimentation. These segments are in Black-and-White, shot mostly on an old hand-cranked camera harking back to the 1920s, with the natural jerks in movement, taking the viewers on a journey into the unknown more than a hundred years ago. It is silent with sub-titles, the treatment slapstick and funny, even as one is amazed by the patience with which Max specially keeps on at his experimentation with his little daughter and enthusiastic brothers pitching in to help. The narrative is filled with unimaginably funny situations treated by Wenders and his team with feather-light touches. One is the scene where Emil’s girlfriend stands in for the great dancer because the original film was burnt by accident. Another similar situation is when the famous dancer decked up in all finery is shocked when she watches this very film with her replacement at a screening for an invited audience. The projector refuses to function when the official inauguration of the screening is arranged.

The little girl functions like a bridge between the past and the present and also is an agency that transcends the two time zones to become omnipresent in both. Wenders himself is often seen along with his crew asking questions of the 91-year-old Lucie who points out that her father Max never wore glasses because in the film, Max is shown always wearing glasses.

Wenders cleverly weaves in the original eight or nine films the Skladanowsky brothers actually made offering the audience the rare opportunity to witness history in the making and in motion. The contemporary scenes are shot in colour and with a modern camera and these span the progress of cinema as a scientific technique over the past 100 years and more. At times, the two eras converge, with spectres of the Skladanowsky clan haunting the contemporary movie set, ultimately suggesting that 1990s Berlin is likewise a society facing momentous transformation.

In this film, Wenders does an interesting experimentation with form when he is actually having the old Lucie interviewed by a team member. We see the technical crew, along with Wenders, juxtaposed against Lucie, in colour, with a little girl playing the little Lucie hovering around. Then, just as suddenly, the screen changes to Black-and-White with the little screen Lucie wandering behind the real, ninety-year-old Lucie. This deliberate blurring of illusion and reality, of fact and fiction, is novel in the scene of the documentary that takes the documentary format one step forward and blurs the difference between the documentary and the fiction film. Images of an enthralled Wenders and his student crew listening to Lucie’s stories and smiling at each other are enhanced with actors playing ghosts of the past wandering around as Lucie goes through her pieces of history laid out across her dining room table.

There are subtle, deliberate, low-key touches of humane, emotional sensibilities that unfold in the dramatised part. The little girl bawling away when one of the brothers has to leave reveals the tight knit character of the family where women seem to be conspicuous by their absence. “This is not authentic” says the old Lucie flashing a toothless smile when she sees the romantic story of the one of the brothers with a local girl built into the narrative.

As the album is opened, she explains the details of every single photograph and one is amazed at the richness of this documentation. This is not just the story of three brothers trying out some crazy experiment in their own eccentric ways. It is also a tragic tale where they found that at the end of it all, the Lumiere Brothers of France walked away with the ‘prize’ of discovering and inventing cinema. A Trick of the Light is an ideal blending of form and content in cinema and the best tribute a filmmaker could have paid to hundred years of cinema.

German, Docu-Fiction, Black & White, Color