Is it not one of the most surprising things about Indian cinema in general and Bengali cinema in particular that no one bothered to write any book in English on one of the greatest actors in Indian cinema – Soumitra Chatterjee? Not very many books on this actor have been published in Bengali either. One, authored by filmmaker Anasua Roychoudhury in Bengali is called Aaj Kaal Porshur Prantey: An Interview with Soumitra Chatterjee. It is one long interview that spans his evolution from his childhood spent in Krishnanagar to his arrival in Calcutta, his deep involvement in theatre and his stepping into films through Satyajit Ray’s Apur Sansar, his first film.

Soumitra Chatterjee has repeatedly insisted that he does not believe in penning an autobiography. Therefore, Amitava Nag’s Beyond Apu: 20 Favourite Roles of Soumitra Chatterjee published by Harper-Collins India appears like a ray of light within the dark tunnel of information and education on this multi-talented actor. Amitava Nag is a passionate lover of films and edits a serious online journal on cinema titled Silhouette published under the auspices of Learning and Creativity.com. Professionally, he is an IT person but his entire spare time is spent watching films, writing about films and discussing films, not necessarily in that order. Therefore, his first book reveals how much he has soaked in the cinema of Soumitra Chatterjee by pushing the borders of his nearly 60 years as an actor to explore his films that reach beyond Ray. The love

Though focussed on the 20 films discussed in detail and analysed by the author, the book also has a chapter on his other talents, such as editing Ekshan one of the most outstanding literary magazines in Bengali for years together, authoring Chatterjee is a noted poet with around a dozen titles to his name. He is a gifted elocutionist and recitation artist who can recite poets from Rabindranath Tagore through Jibanananda Das from memory. He is also a playwright, a translator of plays in other languages, a theatre director and actor. He has worked for radio, television and also did a stint with the jatra form of travelling theatre. If all this is not enough, he also had an art exhibition of his art works though he does not like to talk much about these activities.

The author states that his aim was to focus on the actor functioning on a wider canvas covering a massive horizon of roles and films that would offer the readers an understanding of how versatile he is apart from his durability as an actor which reflects his dependability in an industry fraught with insecurity. Why did the author choose these 20 films along with the actor? In the informative introduction, Nag writes: The popular view is that Soumitra excelled mostly in films of Ray where the general standard of acting is anyway high. The range of roles selected here will dispel the misconception and show how Soumitra excelled over the decades, with several directors and in different profiles. Even while playing the romantic lead, he is more like a character than a typical star-her. (p.xvi)

However, having said that, of the 20 films explored in the book, nine films are directed by Ray. An added attraction is a small handwritten note by the actor himself written on his personal letterhead where he says that the delimiting factor was choosing 20 films which made him keep ‘quite many which are dear to me but I have to keep them off from the list’. Chatterjee sounds happy because this is the first ever book in English where the subject is Soumitra Chatterjee.

The book also carries a 21-page interview of the actor by the author where Chatterjee, not easy to pin down for an interview, opens up on the many dimensions of his career in acting as well as his sincere forays into poetry, literature, theatre and so on.

One rare insight one gets is when the actor recalls that he was informed of his mother’s death (at the age of 97) while he was on stage performing his autobiographical play Tritiyo Onko Otoeb. “I was told during the break. She was quite critical for a few days before that. The first act after the break is when I recollect my childhood and how my mother used to control us. So it could have been very emotional. I had to make sure I didn’t let my emotions get the better of me. After all, I am a professional actor.” (pp.147-148). At another point, Chatterjee says: “The letter he (Satyajit Ray) gave to Cine Central (a film society in Kolkata) when they held a retrospective, Teen Doshoker Soumitra (Three Decdaes of Soumitra) in 1990 is the ultimate tribute that I can expect: ‘I will have faith in Soumitra till the last day of my creative life.’ I cannot expect anything higher than this in my life.” (p.157).

He has directed and acted in more than a dozen plays. Chatterjee has given Public Theatre a completely different look from many standpoints. His plays focus on contemporary life mixed with crisis and confrontation.” His first play was Mukhosh, the Bengali adaptation of Jacob’s The Monkey’s Paw which he directed while still a student. The play won the first prize at the Inter-University Drama Contest in Delhi in 1956. His next play was Bidehi adapted from Ibsen’s Ghost. But recognition came with his sterling production of Naamjibon with which he established himself firmly into the professional stage of Kolkata. Other successful plays include Tiktiki (Sleuth), Atmakatha (the Bengali adaptation of Mahesh Elkunchwar’s famous Marathi play) and most recently, Raja Lear adapted from Shakespeare’s King Lear.

This critic discovered to her pleasant surprise that she had watched all but one of the 20 films chosen for this book and most of them, more than once. The exception was Agradani, based, according to Chatterjee himself, on one of the ten most brilliant short stories in Bengali. The story was authored by Jnanpeeth Award winner Tarashankar Banerjee and the film was produced by a family member of the author many years later. Nag brackets it within the Chatterjee’s two ‘subaltern’ depictions. Agradani is the tragic story of a lower-caste Brahmin who belonged to a caste where the Brahmins were appointed only to savour the pinda offered to the departed soul. It is also a very informative film which did good business in the villages but was hardly watched in the cities because Soumitra wore very dark make-up and was made to look like a village bumpkin who loved to eat and led an aimless life which did not jell with the urban audience’s image of Soumitra Chatterjee. Says Soumitra, “I would have been happier if there were more films like Agradani where I could reach out to more people.” (p.162).

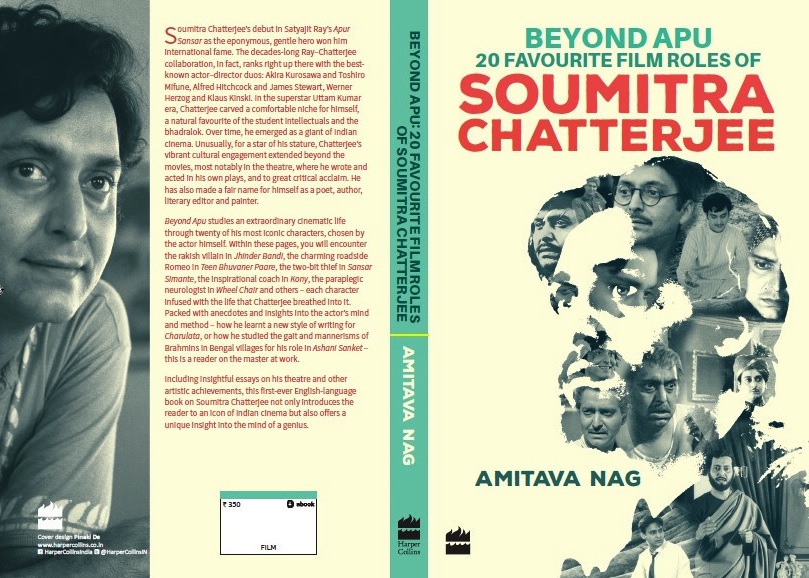

The well-bound book with high resolution images and good production values is further enriched by the outstanding collage of Pinaki De’s for the front cover. This book will definitely add to the all film libraries across the world and as frames of reference, appeal to all overs of Indian cinema in general and Bengali cinema in particular. Contemporary Indian actors can perhaps pick out pages from the book to find out what it takes to acquire this unparalleled position as a star-actor for more than fifty long years.